- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 866

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Reactions

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

"How did Paleolithic people arrive at such remote islands as Okinawa? What tools and strategies did they use?"

Crossing the Kuroshio current in a handmade replica of a Paleolithic dugout canoe. Credit: Kaifu et al. CC-By-ND

Earlier this week, we reported on a Swedish archaeologist who spent the last three years sailing the fjords in a replica boat similar to those the Vikings may have used. Not to be outdone, Japanese researchers have followed suit, building their own seaworthy dugout canoe with Paleolithic-era tools to cross between Taiwan and Yonaguni Island, where one of the world’s strongest ocean currents, the Kuroshio, remains active.

They presented their findings in two new papers published in the journal Science Advances. One describes the experimental trial, and the other involves numerical simulations to investigate the general conditions needed for the crossing. The successfully re-enacted voyage suggests that early modern humans likely had a high level of strategic seafaring knowledge. (You can watch a 90-minute documentary about the voyage here.) This would explain the presence of archaeological evidence that Paleolithic people made the crossing some 30,000 years ago without the aid of maps, metal tools, or modern boats.

“We initiated this project with simple questions: ‘How did Paleolithic people arrive at such remote islands as Okinawa? How difficult was their journey? And what tools and strategies did they use?’” said co-author Yousuke Kaifu of the University of Tokyo. “Archaeological evidence such as remains and artifacts can’t paint a full picture as the nature of the sea is that it washes such things away. So we turned to the idea of experimental archaeology, in a similar vein to the Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947 by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl.”

Kaifu and his team have been working on their voyage re-enactment project since 2013, although it wasn't formalized until three years later. They first considered reed-bundle rafts and bamboo rafts—constructed with locally available materials—as possible candidate watercraft that Paleolithic people may have used for the crossing. But both rafts proved to be too difficult to control on the open sea. A faster, more durable boat would be needed.

A grueling 45-hour journey

The team used replica tools and a real tree. Credit: Kaifu et al., 2025/CC-By-ND

So they turned to the dugout canoe. Granted, to date, there is no physical archaeological evidence that dugouts existed in the Paleolithic Ryukyus, but excavators have unearthed edge-ground stone axes from that period in Japan, which would have enabled the building of a dugout canoe. However, archaeologists have unearthed the remains of dugout canoes and wooden single-bladed paddles from the Jomon period. Since there is no corresponding evidence of sailing technology or planked boats, Kaifu et al. concluded that a dugout canoe was a reasonable candidate.

As much as possible, the team sought to use tools and practices on par with what would have been available to the Paleolithic people. It took six days to cut down a Japanese cedar tree with replica edge-ground stone axes. This used up their supply, so they relied on thicker-bladed replica axes for cutting and shaping the 7-5-meter dugout out of the heartwood, as well as for making the paddles. They polished the outer and inner surfaces with fire and stone and nicknamed the completed dugout "Sugime." They also installed crude wooden seats to make the crew more comfortable.

For the test voyage, Kaifu et al. selected the Ryukyus strait between Taiwan and Yonaguni Island, where there are no effective tailwinds, the Kuroshio current flows northward, and the target island is not visible for more than the first half of the voyage, limiting its usefulness for navigation. They recruited a team of five experienced paddlers to make what turned out to be a grueling 45-hour voyage.

When the paddlers encountered choppy sea conditions, they noted that the canoe tended to rotate northward. And they learned to keep an eye out for large waves inbound from the north, temporarily turning the bow northward to ride them out. There was little rest for the paddlers in order to keep the boat from capsizing on the first day, and by the second, the crew was tired, sleep-deprived, very hot, and uncertain about their precise position since the target island was not yet in sight. They experienced stomach cramps, abdominal muscle pain, and even hallucinations, but they persevered.

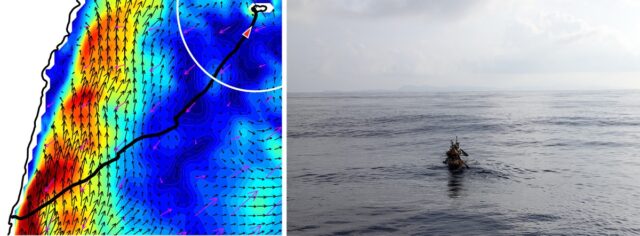

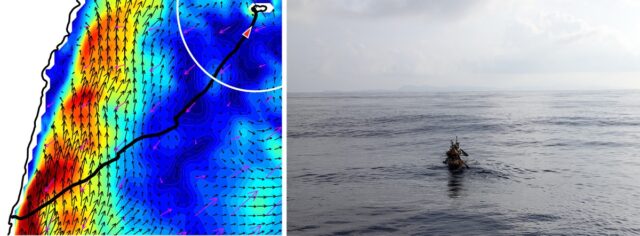

(Left) GPS tracking and modeling of ocean currents toward the end of the experimental voyage. (Right) The team on the water around the time of the left image. Credit: Kaifu et al., 2025/CC-By-ND

At the 30-hour mark, the captain ordered the entire crew to rest, letting the dugout drift freely for a while, which fortunately brought them closer to Yonaguni Island. At hour 40, the island's silhouette was visible, and over the next five hours, the crew was able to navigate the strong tidal flow along the coast until they reached their landing site: Nama Beach. So the experimental voyage was a success, augmented by the numerical simulations to demonstrate that the boat could make similar voyages from different departure points across both modern and late-Pleistocene oceans.

Granted, it was not possible to recreate Paleolithic conditions perfectly on a modern ocean. The crew first spotted the island because of its artificial lights, although by that time, they were on track navigationally. They were also accompanied by escort ships to ensure the crew's safety, supplying fresh water twice during the voyage. But the escort ships did not aid with navigation or the dugout captain's decision-making, and the authors believe that any effects were likely minimal. The biggest difference was the paddlers' basic modern knowledge of local geography, which helped them develop a navigation plan—an unavoidable anachronism, although the crew did not rely on compasses, GPS, or watches during the voyage.

“Scientists try to reconstruct the processes of past human migrations, but it is often difficult to examine how challenging they really were," said Kaifu. "One important message from the whole project was that our Paleolithic ancestors were real challengers. Like us today, they had to undertake strategic challenges to advance. For example, the ancient Polynesian people had no maps, but they could travel almost the entire Pacific. There are a variety of signs on the ocean to know the right direction, such as visible land masses, heavenly bodies, swells, and winds. We learned parts of such techniques ourselves along the way.”

“Traversing the Kuroshio: Paleolithic migration across one of the world's strongest ocean currents,” Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv5508 (About DOIs).

“Palaeolithic seafaring in East Asia: an experimental test of the dugout canoe hypothesis," Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv5507

Crossing the Kuroshio current in a handmade replica of a Paleolithic dugout canoe. Credit: Kaifu et al. CC-By-ND

Earlier this week, we reported on a Swedish archaeologist who spent the last three years sailing the fjords in a replica boat similar to those the Vikings may have used. Not to be outdone, Japanese researchers have followed suit, building their own seaworthy dugout canoe with Paleolithic-era tools to cross between Taiwan and Yonaguni Island, where one of the world’s strongest ocean currents, the Kuroshio, remains active.

They presented their findings in two new papers published in the journal Science Advances. One describes the experimental trial, and the other involves numerical simulations to investigate the general conditions needed for the crossing. The successfully re-enacted voyage suggests that early modern humans likely had a high level of strategic seafaring knowledge. (You can watch a 90-minute documentary about the voyage here.) This would explain the presence of archaeological evidence that Paleolithic people made the crossing some 30,000 years ago without the aid of maps, metal tools, or modern boats.

“We initiated this project with simple questions: ‘How did Paleolithic people arrive at such remote islands as Okinawa? How difficult was their journey? And what tools and strategies did they use?’” said co-author Yousuke Kaifu of the University of Tokyo. “Archaeological evidence such as remains and artifacts can’t paint a full picture as the nature of the sea is that it washes such things away. So we turned to the idea of experimental archaeology, in a similar vein to the Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947 by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl.”

Kaifu and his team have been working on their voyage re-enactment project since 2013, although it wasn't formalized until three years later. They first considered reed-bundle rafts and bamboo rafts—constructed with locally available materials—as possible candidate watercraft that Paleolithic people may have used for the crossing. But both rafts proved to be too difficult to control on the open sea. A faster, more durable boat would be needed.

A grueling 45-hour journey

The team used replica tools and a real tree. Credit: Kaifu et al., 2025/CC-By-ND

So they turned to the dugout canoe. Granted, to date, there is no physical archaeological evidence that dugouts existed in the Paleolithic Ryukyus, but excavators have unearthed edge-ground stone axes from that period in Japan, which would have enabled the building of a dugout canoe. However, archaeologists have unearthed the remains of dugout canoes and wooden single-bladed paddles from the Jomon period. Since there is no corresponding evidence of sailing technology or planked boats, Kaifu et al. concluded that a dugout canoe was a reasonable candidate.

As much as possible, the team sought to use tools and practices on par with what would have been available to the Paleolithic people. It took six days to cut down a Japanese cedar tree with replica edge-ground stone axes. This used up their supply, so they relied on thicker-bladed replica axes for cutting and shaping the 7-5-meter dugout out of the heartwood, as well as for making the paddles. They polished the outer and inner surfaces with fire and stone and nicknamed the completed dugout "Sugime." They also installed crude wooden seats to make the crew more comfortable.

For the test voyage, Kaifu et al. selected the Ryukyus strait between Taiwan and Yonaguni Island, where there are no effective tailwinds, the Kuroshio current flows northward, and the target island is not visible for more than the first half of the voyage, limiting its usefulness for navigation. They recruited a team of five experienced paddlers to make what turned out to be a grueling 45-hour voyage.

When the paddlers encountered choppy sea conditions, they noted that the canoe tended to rotate northward. And they learned to keep an eye out for large waves inbound from the north, temporarily turning the bow northward to ride them out. There was little rest for the paddlers in order to keep the boat from capsizing on the first day, and by the second, the crew was tired, sleep-deprived, very hot, and uncertain about their precise position since the target island was not yet in sight. They experienced stomach cramps, abdominal muscle pain, and even hallucinations, but they persevered.

(Left) GPS tracking and modeling of ocean currents toward the end of the experimental voyage. (Right) The team on the water around the time of the left image. Credit: Kaifu et al., 2025/CC-By-ND

At the 30-hour mark, the captain ordered the entire crew to rest, letting the dugout drift freely for a while, which fortunately brought them closer to Yonaguni Island. At hour 40, the island's silhouette was visible, and over the next five hours, the crew was able to navigate the strong tidal flow along the coast until they reached their landing site: Nama Beach. So the experimental voyage was a success, augmented by the numerical simulations to demonstrate that the boat could make similar voyages from different departure points across both modern and late-Pleistocene oceans.

Granted, it was not possible to recreate Paleolithic conditions perfectly on a modern ocean. The crew first spotted the island because of its artificial lights, although by that time, they were on track navigationally. They were also accompanied by escort ships to ensure the crew's safety, supplying fresh water twice during the voyage. But the escort ships did not aid with navigation or the dugout captain's decision-making, and the authors believe that any effects were likely minimal. The biggest difference was the paddlers' basic modern knowledge of local geography, which helped them develop a navigation plan—an unavoidable anachronism, although the crew did not rely on compasses, GPS, or watches during the voyage.

“Scientists try to reconstruct the processes of past human migrations, but it is often difficult to examine how challenging they really were," said Kaifu. "One important message from the whole project was that our Paleolithic ancestors were real challengers. Like us today, they had to undertake strategic challenges to advance. For example, the ancient Polynesian people had no maps, but they could travel almost the entire Pacific. There are a variety of signs on the ocean to know the right direction, such as visible land masses, heavenly bodies, swells, and winds. We learned parts of such techniques ourselves along the way.”

“Traversing the Kuroshio: Paleolithic migration across one of the world's strongest ocean currents,” Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv5508 (About DOIs).

“Palaeolithic seafaring in East Asia: an experimental test of the dugout canoe hypothesis," Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv5507