- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 866

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Reactions

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

The boomerang is a one-of-a-kind find from the last place archaeologists expected.

The boomerang is about 72 centimeters long. Credit: Talamo et al. 2025

A boomerang carved from a mammoth tusk is one of the oldest in the world, and it may be even older than archaeologists originally thought, according to a recent round of radiocarbon dating.

Archaeologists unearthed the mammoth-tusk boomerang in Poland’s Oblazowa Cave in the 1990s, and they originally dated it to around 18,000 years old, which made it one of the world’s oldest intact boomerangs. But according to recent analysis by University of Bologna researcher Sahra Talamo and her colleagues, the boomerang may have been made around 40,000 years ago. If they’re right, it offers tantalizing clues about how people lived on the harsh tundra of what’s now Poland during the last Ice Age.

A boomerang carved from mammoth tusk

The mammoth-tusk boomerang is about 72 centimeters long, gently curved, and shaped so that one end is slightly more rounded than the other. It still bears scratches and scuffs from the mammoth’s life, along with fine, parallel grooves that mark where some ancient craftsperson shaped and smoothed the boomerang. On the rounded end, a series of diagonal marks would have made the weapon easier to grip. It’s smoothed and worn from frequent handling: the last traces of the life of some Paleolithic hunter.

Based on experiments with a replica, the Polish mammoth boomerang flies smoothly but doesn’t return, similar to certain types of Aboriginal Australian boomerangs. In fact, it looks a lot like a style used by Aboriginal people from Queensland, Australia, but that’s a case of people in different times and places coming up with very similar designs to fit similar needs.

But critically, according to Talamo and her colleagues, the boomerang is about 40,000 years old.

That’s a huge leap from the original radiocarbon date, made in 1996, which was based on a sample of material from the boomerang itself and estimated an age of 18,000 years. But Talamo and her colleagues claim that original date didn’t line up well with the ages of other nearby artifacts from the same layer of the cave floor. That made them suspect that the boomerang sample may have gotten contaminated by modern carbon somewhere along the way, making it look younger. To test the idea, the archaeologists radiocarbon dated samples from 13 animal bones—plus one from a human thumb—unearthed from the same layer of cave floor sediment as the boomerang.

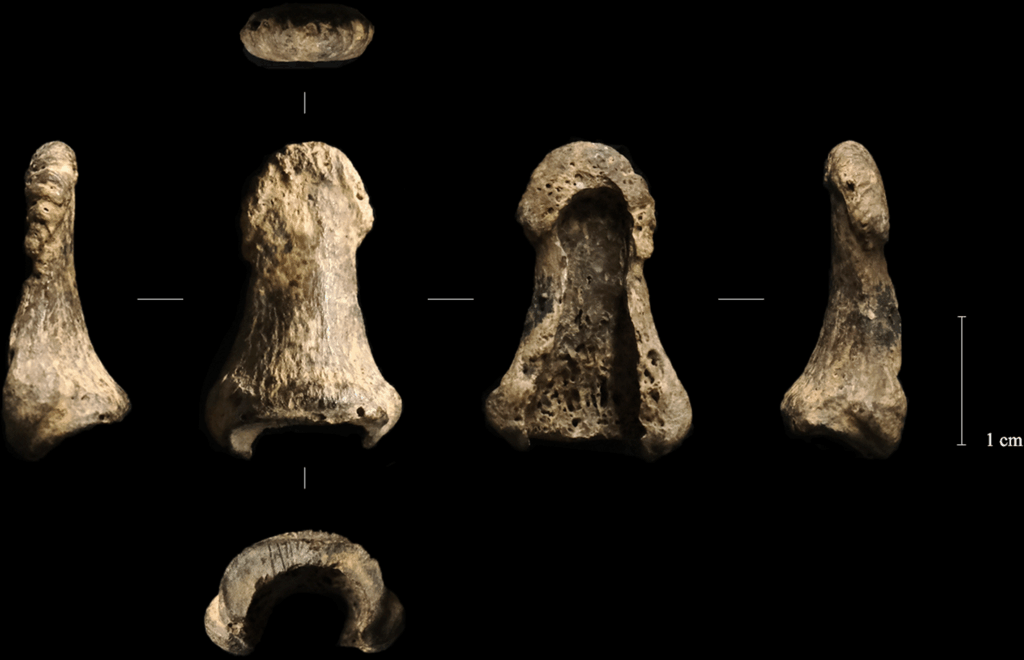

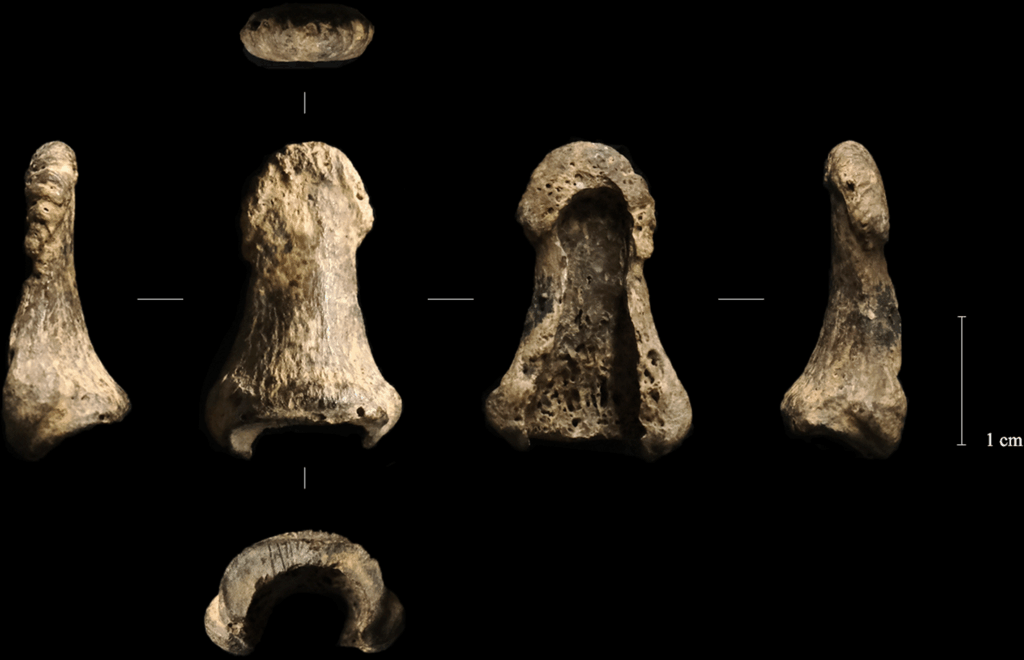

This left distal phalanx was found not far from the mammoth tusk boomerang. Credit: Talamo et al. 2025

What about the human thumb?

The human thumb-bone (or left distal phalanx, if you’re feeling fancy) is an intriguing part of the boomerang’s story. Archaeologists found the boomerang buried near a circle of boulders in the center of the cave chamber, buried alongside tools made from antlers, a pair of arctic fox-tooth pendants, a bone bead... oh, and the last bone from someone’s left thumb.

Talamo and her colleagues speculate that there was some kind of ritual involved (archaeologists in general are fond of such speculation, but there may be something to it in this case). The boulders “appear to have been transported from the nearby river and intentionally placed,” they write in their paper.

So not only is this a boomerang carved from a mammoth tusk, and not only does it apparently date to a period when most paleoanthropologists have thought central and northern Europe were largely deserted, but it may have been part of a ritual so ancient that we have no way of reconstructing its meaning or details.

Surviving in a prehistoric climatic wasteland

Archaeologists aren’t sure who invented boomerangs first, but at various times in human history, people on at least three continents seem to have thought to use a curved, flat stick that spins as it flies through the air to hit a target. Examples have been found in Africa, Australia, and Europe. In other words, boomerangs, like spears and bows, seem to be a frequent solution to the same basic problem: how to hit things with a stick.

Welcome to Oblazowa Cave, Poland. Credit: Talamo et al. 2025

Even at 18,000 years old, the mammoth boomerang was already among the oldest examples of spinning-flying-flat-stick technology (some might even have called it revolutionary) in the world. But with the updated age estimate, the Oblazowa Cave boomerang reveals some interesting things about the people who lived in what’s now Poland during the last Ice Age.

Until recently, it looked as though central and northern Europe lay uninhabited for thousands of years after the last Neanderthals either left or died out.

“Environmental shifts after 42,000 years ago, associated with central European climatic deterioration, positioned the cold-steppe landscapes north of 49 degrees North as challenging for sustained settlements,” write Talamo and her colleagues. In other words, a cold and hostile climate made the northern half of Europe sort of a prehistoric postapocalyptic wasteland—or not, according to the new dates from Oblazowa Cave.

When Talamo and her colleagues dated the animal bones and the human phalanx, the results suggested that people had lived in Oblazowa Cave for about 3,500 years during this period of “climatic deterioration.” They apparently stayed through phases of relative warmth and deeper cold. That demonstrates what Talamo and her colleagues describe as “resilience in the face of environmental variability.” And not only were people making a living at Oblazowa Cave, they were faring well enough to make something as time-consuming, labor-intensive, and frankly inconvenient as a mammoth ivory boomerang.

Red stripes make it go faster

“This boomerang reflects a unique choice by the group at Oblazowa Cave,” write Talamo and her colleagues, and it’s hard not to read that in a slightly bemused tone.

Unlike stone spear points and wooden spears or throwing sticks, or even wooden boomerangs, this was a tool that would have taken huge amounts of time and work to create—things that are in short supply when your lifestyle is built around mobility. But someone (or maybe multiple people, we don’t know) invested the effort to carve the shape of the boomerang from a solid mammoth tusk. Female woolly mammoth tusks could be up to 9.3 centimeters thick, and male tusks could boast diameters up to 18 centimeters, which meant that someone had to chip away a lot of ivory to get the thin, flattish shape of the boomerang, then smooth it into just the geometry to make it fly properly.

And not only did someone go to the effort of making the boomerang, they even decorated it; it’s marked with deep, wide incisions, and they contain traces of red pigment. The boomerang was clearly made to be used, but it wasn’t purely utilitarian; someone wanted this thing to look cool while it was whizzing through the air.

PLOS One, 2025. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324911 (About DOIs).

The boomerang is about 72 centimeters long. Credit: Talamo et al. 2025

A boomerang carved from a mammoth tusk is one of the oldest in the world, and it may be even older than archaeologists originally thought, according to a recent round of radiocarbon dating.

Archaeologists unearthed the mammoth-tusk boomerang in Poland’s Oblazowa Cave in the 1990s, and they originally dated it to around 18,000 years old, which made it one of the world’s oldest intact boomerangs. But according to recent analysis by University of Bologna researcher Sahra Talamo and her colleagues, the boomerang may have been made around 40,000 years ago. If they’re right, it offers tantalizing clues about how people lived on the harsh tundra of what’s now Poland during the last Ice Age.

A boomerang carved from mammoth tusk

The mammoth-tusk boomerang is about 72 centimeters long, gently curved, and shaped so that one end is slightly more rounded than the other. It still bears scratches and scuffs from the mammoth’s life, along with fine, parallel grooves that mark where some ancient craftsperson shaped and smoothed the boomerang. On the rounded end, a series of diagonal marks would have made the weapon easier to grip. It’s smoothed and worn from frequent handling: the last traces of the life of some Paleolithic hunter.

Based on experiments with a replica, the Polish mammoth boomerang flies smoothly but doesn’t return, similar to certain types of Aboriginal Australian boomerangs. In fact, it looks a lot like a style used by Aboriginal people from Queensland, Australia, but that’s a case of people in different times and places coming up with very similar designs to fit similar needs.

But critically, according to Talamo and her colleagues, the boomerang is about 40,000 years old.

That’s a huge leap from the original radiocarbon date, made in 1996, which was based on a sample of material from the boomerang itself and estimated an age of 18,000 years. But Talamo and her colleagues claim that original date didn’t line up well with the ages of other nearby artifacts from the same layer of the cave floor. That made them suspect that the boomerang sample may have gotten contaminated by modern carbon somewhere along the way, making it look younger. To test the idea, the archaeologists radiocarbon dated samples from 13 animal bones—plus one from a human thumb—unearthed from the same layer of cave floor sediment as the boomerang.

This left distal phalanx was found not far from the mammoth tusk boomerang. Credit: Talamo et al. 2025

What about the human thumb?

The human thumb-bone (or left distal phalanx, if you’re feeling fancy) is an intriguing part of the boomerang’s story. Archaeologists found the boomerang buried near a circle of boulders in the center of the cave chamber, buried alongside tools made from antlers, a pair of arctic fox-tooth pendants, a bone bead... oh, and the last bone from someone’s left thumb.

Talamo and her colleagues speculate that there was some kind of ritual involved (archaeologists in general are fond of such speculation, but there may be something to it in this case). The boulders “appear to have been transported from the nearby river and intentionally placed,” they write in their paper.

So not only is this a boomerang carved from a mammoth tusk, and not only does it apparently date to a period when most paleoanthropologists have thought central and northern Europe were largely deserted, but it may have been part of a ritual so ancient that we have no way of reconstructing its meaning or details.

Surviving in a prehistoric climatic wasteland

Archaeologists aren’t sure who invented boomerangs first, but at various times in human history, people on at least three continents seem to have thought to use a curved, flat stick that spins as it flies through the air to hit a target. Examples have been found in Africa, Australia, and Europe. In other words, boomerangs, like spears and bows, seem to be a frequent solution to the same basic problem: how to hit things with a stick.

Welcome to Oblazowa Cave, Poland. Credit: Talamo et al. 2025

Even at 18,000 years old, the mammoth boomerang was already among the oldest examples of spinning-flying-flat-stick technology (some might even have called it revolutionary) in the world. But with the updated age estimate, the Oblazowa Cave boomerang reveals some interesting things about the people who lived in what’s now Poland during the last Ice Age.

Until recently, it looked as though central and northern Europe lay uninhabited for thousands of years after the last Neanderthals either left or died out.

“Environmental shifts after 42,000 years ago, associated with central European climatic deterioration, positioned the cold-steppe landscapes north of 49 degrees North as challenging for sustained settlements,” write Talamo and her colleagues. In other words, a cold and hostile climate made the northern half of Europe sort of a prehistoric postapocalyptic wasteland—or not, according to the new dates from Oblazowa Cave.

When Talamo and her colleagues dated the animal bones and the human phalanx, the results suggested that people had lived in Oblazowa Cave for about 3,500 years during this period of “climatic deterioration.” They apparently stayed through phases of relative warmth and deeper cold. That demonstrates what Talamo and her colleagues describe as “resilience in the face of environmental variability.” And not only were people making a living at Oblazowa Cave, they were faring well enough to make something as time-consuming, labor-intensive, and frankly inconvenient as a mammoth ivory boomerang.

Red stripes make it go faster

“This boomerang reflects a unique choice by the group at Oblazowa Cave,” write Talamo and her colleagues, and it’s hard not to read that in a slightly bemused tone.

Unlike stone spear points and wooden spears or throwing sticks, or even wooden boomerangs, this was a tool that would have taken huge amounts of time and work to create—things that are in short supply when your lifestyle is built around mobility. But someone (or maybe multiple people, we don’t know) invested the effort to carve the shape of the boomerang from a solid mammoth tusk. Female woolly mammoth tusks could be up to 9.3 centimeters thick, and male tusks could boast diameters up to 18 centimeters, which meant that someone had to chip away a lot of ivory to get the thin, flattish shape of the boomerang, then smooth it into just the geometry to make it fly properly.

And not only did someone go to the effort of making the boomerang, they even decorated it; it’s marked with deep, wide incisions, and they contain traces of red pigment. The boomerang was clearly made to be used, but it wasn’t purely utilitarian; someone wanted this thing to look cool while it was whizzing through the air.

PLOS One, 2025. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324911 (About DOIs).