- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 917

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

"If you want to make foodborne disease go away, then don’t look for foodborne disease."

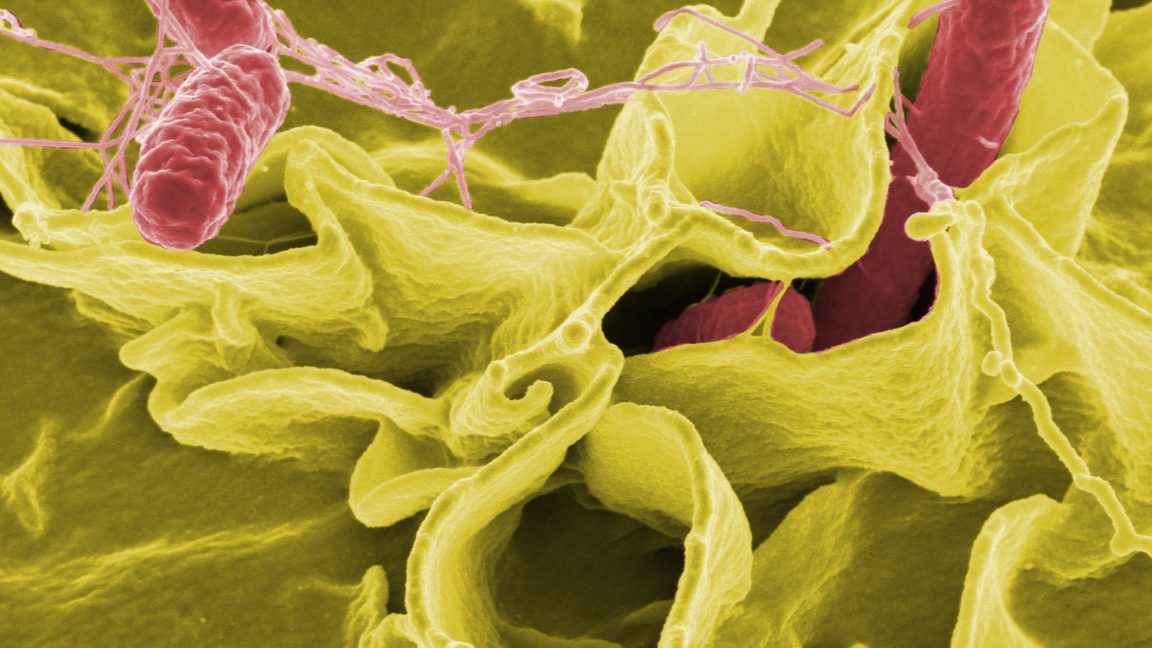

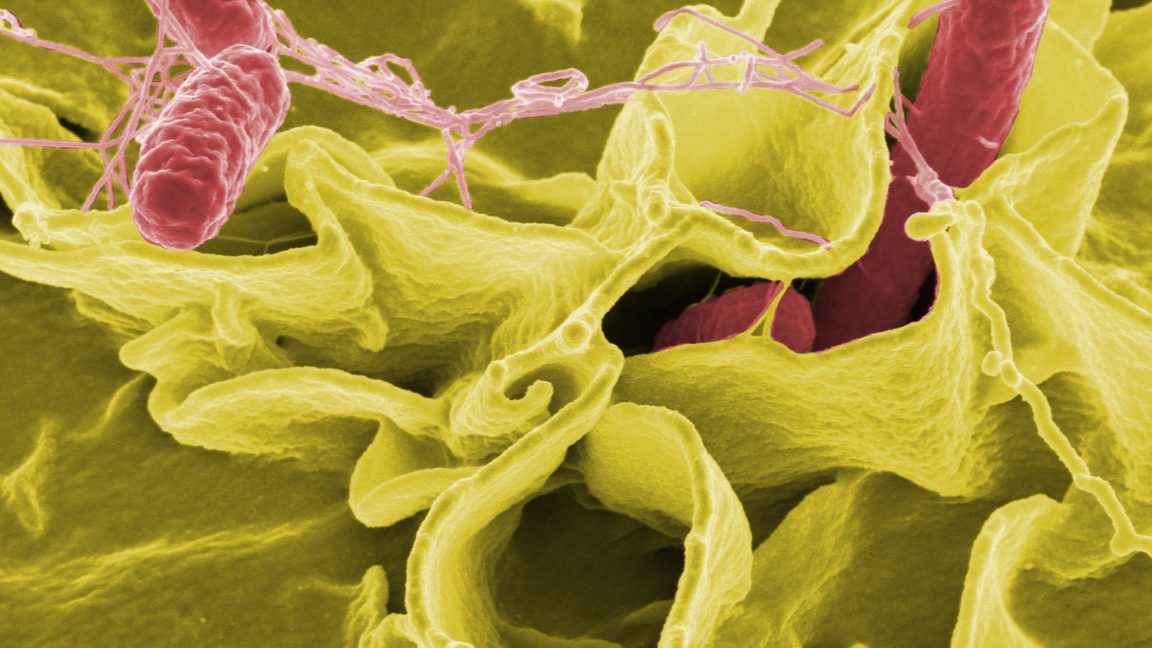

Credit: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH

In July, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dramatically, but quietly, scaled back a food safety surveillance system, cutting active tracking from eight top foodborne infections down to just two, according to a report by NBC News.

The Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet)—a network of surveillance sites that spans 10 states and covers about 54 million Americans (16 percent of the US population)—previously included active monitoring for eight infections from pathogens. Those include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia.

Now the network is only monitoring for STEC and Salmonella.

A list of talking points the CDC sent the Connecticut health department (which is part of FoodNet) suggested that a lack of funding is behind the scaleback. "Funding has not kept pace with the resources required to maintain the continuation of FoodNet surveillance for all eight pathogens," the CDC document said, according to NBC. The Trump administration has made brutal cuts to federal agencies, including the CDC, which has lost hundreds of employees this year.

A CDC spokesperson told the outlet that "Although FoodNet will narrow its focus to Salmonella and STEC, it will maintain both its infrastructure and the quality it has come to represent. Narrowing FoodNet’s reporting requirements and associated activities will allow FoodNet staff to prioritize core activities."

The CDC does maintain other surveillance systems that can collect data on infections, including the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. And the CDC’s Listeria Initiative. However, these systems are for passive monitoring, while FoodNet was the only active system that sought case identification.

Food safety experts fear that the cuts will make it difficult for the CDC to monitor trends and quickly identify when cases increase at the outset of an outbreak. They also fear that weakening surveillance data will lead to less awareness of foodborne threats, and thus, less perceived need for food safety regulations.

"If you want to make foodborne disease go away, then don’t look for foodborne disease," J. Glenn Morris, director of the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida told NBC News. "And then you can cheerfully eliminate all of your foodborne disease regulations. My concern is that that is the path down which we appear to be heading."

Credit: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH

In July, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dramatically, but quietly, scaled back a food safety surveillance system, cutting active tracking from eight top foodborne infections down to just two, according to a report by NBC News.

The Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet)—a network of surveillance sites that spans 10 states and covers about 54 million Americans (16 percent of the US population)—previously included active monitoring for eight infections from pathogens. Those include Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Listeria, Salmonella, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), Shigella, Vibrio, and Yersinia.

Now the network is only monitoring for STEC and Salmonella.

A list of talking points the CDC sent the Connecticut health department (which is part of FoodNet) suggested that a lack of funding is behind the scaleback. "Funding has not kept pace with the resources required to maintain the continuation of FoodNet surveillance for all eight pathogens," the CDC document said, according to NBC. The Trump administration has made brutal cuts to federal agencies, including the CDC, which has lost hundreds of employees this year.

A CDC spokesperson told the outlet that "Although FoodNet will narrow its focus to Salmonella and STEC, it will maintain both its infrastructure and the quality it has come to represent. Narrowing FoodNet’s reporting requirements and associated activities will allow FoodNet staff to prioritize core activities."

The CDC does maintain other surveillance systems that can collect data on infections, including the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. And the CDC’s Listeria Initiative. However, these systems are for passive monitoring, while FoodNet was the only active system that sought case identification.

Food safety experts fear that the cuts will make it difficult for the CDC to monitor trends and quickly identify when cases increase at the outset of an outbreak. They also fear that weakening surveillance data will lead to less awareness of foodborne threats, and thus, less perceived need for food safety regulations.

"If you want to make foodborne disease go away, then don’t look for foodborne disease," J. Glenn Morris, director of the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida told NBC News. "And then you can cheerfully eliminate all of your foodborne disease regulations. My concern is that that is the path down which we appear to be heading."