- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 827

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

Community watch groups have a playbook to keep ICE away from subscriber information.

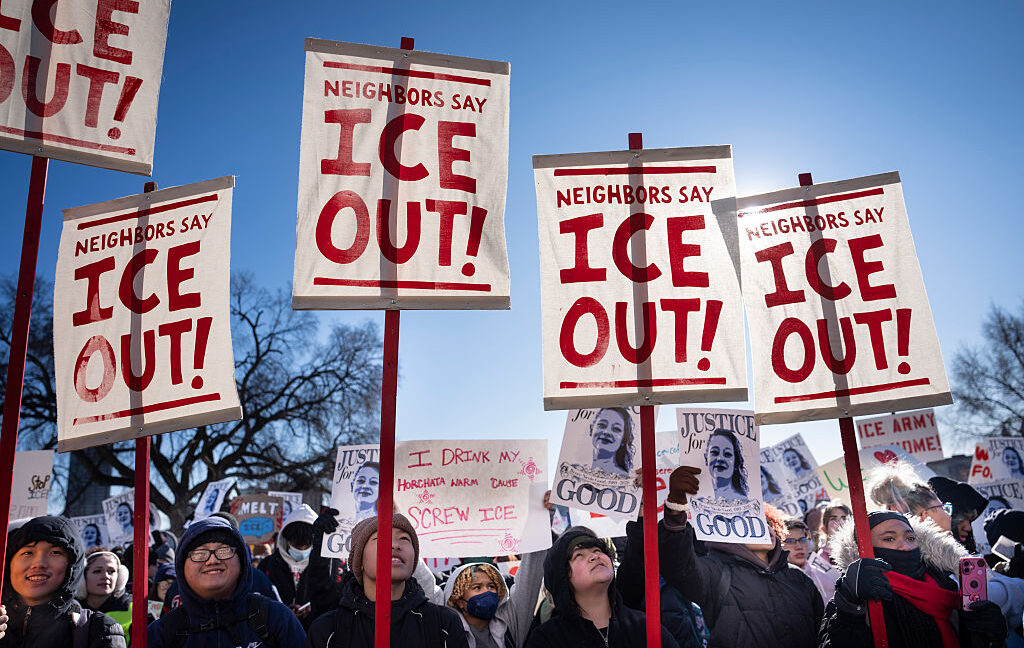

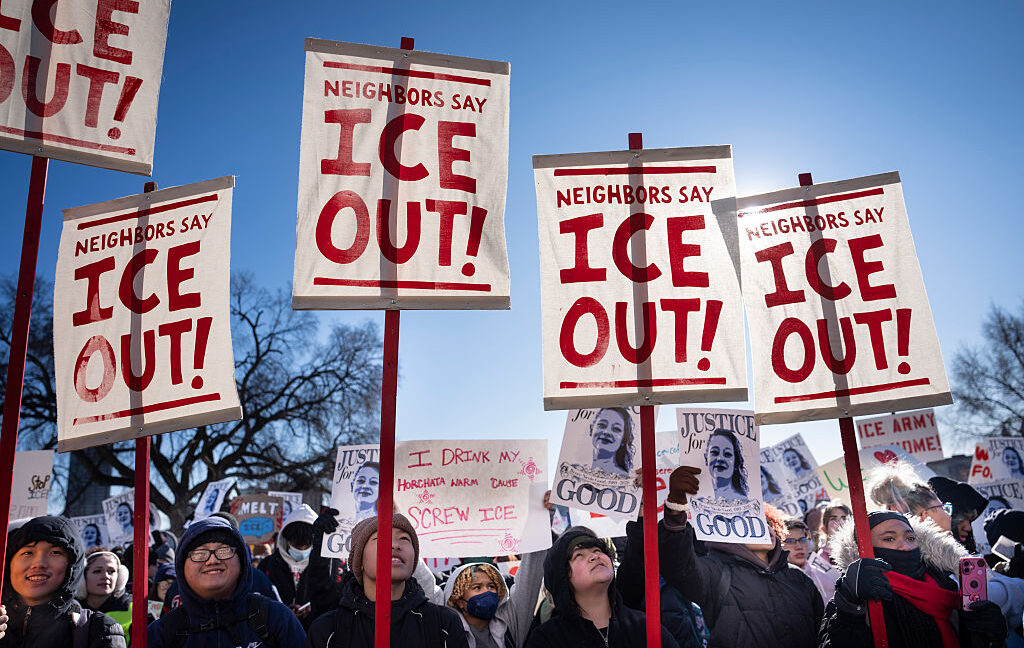

Students from St. Paul public schools protest at a massive walkout to the State Capitol in St. Paul, Minn., to protest ICE actions in Minnesota. Credit: Star Tribune via Getty Images / Contributor | Star Tribune

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has backed down from a fight to unmask the owners of Instagram and Facebook accounts monitoring Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activity in Pennsylvania.

One of the anonymous account holders, John Doe, sued to block ICE from identifying him and other critics online through summonses to Meta that he claimed infringed on core First Amendment-protected activity.

DHS initially fought Doe’s motion to quash the summonses, arguing that the community watch groups endangered ICE agents by posting “pictures and videos of agents’ faces, license plates, and weapons, among other things.” This was akin to “threatening ICE agents to impede the performance of their duties,” DHS alleged. DHS’s arguments echoed DHS Secretary Kristi Noem, who has claimed that identifying ICE agents is a crime, even though Wired noted that ICE employees often post easily discoverable LinkedIn profiles.

To Doe, the agency seemed intent on testing the waters to see if it could seize authority to unmask all critics online by invoking a customs statute that allows agents to subpoena information on goods entering or leaving the US.

But then, on January 16, DHS abruptly reversed course, withdrawing its summonses from Meta.

A court filing confirmed that DHS dropped its requests for subscriber information last week, after initially demanding Doe’s “postal code, country, all email address(es) on file, date of account creation, registered telephone numbers, IP address at account signup, and logs showing IP address and date stamps for account accesses.”

The filing does not explain why DHS decided to withdraw its requests.

However, previously, DHS requested similar information from Meta about six Instagram community watch groups that shared information about ICE activity in Los Angeles and other locations. DHS withdrew those requests, too, after account holders defended their First Amendment rights and filed motions to quash their summonses, Doe’s court filing said.

To defeat DHS’ summonses, Doe shared all his group’s online posts with the court. An attorney representing Doe at the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, Ariel Shapell, told Ars that Doe’s groups posted “pretty innocuous” content, like “information and resources about immigrant rights, due process rights, fundraising, and vigils.”

It’s possible DHS caved due to lack of evidence supporting claims that Doe’s groups’ posts carried implicit threats to “assault, kidnap, or murder any federal official,” as DHS had argued. But it’s also possible that DHS keeps trying and failing to unmask ICE critics due to strong First Amendment protections working to preserve the right to post anonymously online.

DHS faces spiking ICE criticism

The attempt to unmask Doe’s accounts came as criticism of ICE is mounting nationwide, and a win could have given ICE broad authority to attack that growing base of critics if DHS had dug in and its defense actually held.

DHS’s withdrawal of the summonses could signal that the argument the agency tried to raise—weirdly using a statute tied to the “importation/exportation of merchandise” to seize “unlimited subpoena authority” of ICE critics online—is clearly not a winning one.

Meta did not immediately respond to Ars’ request for comment. But Meta did play a role in challenging DHS’ summonses, initially by seeking more information from the agency and then notifying account holders to provide an opportunity to quash the summonses before information was shared.

So far, the playbook for community watch groups on Facebook and Instagram has been to follow Meta’s advice in order to block identifying information from being shared. But it remains unclear if Meta may have complied with DHS’s requests if account holders were not able to legally fight to quash them, perhaps leaving a vulnerable gray area for community watch groups.

For Doe and any others involved in “MontCo Community Watch,” DHS’s withdrawal of the summonses likely comes as a relief. But this wasn’t the first time DHS tried and failed to unmask online critics, so it’s just as likely that fears remain that DHS will continue trying to identify groups that are posting footage to raise awareness of ICE’s most controversial moves.

ICE critics have used footage of tragic events—like Renee Good’s killing and eight other ICE shootings since September—to support calls to remove ICE from embattled communities and abolish ICE.

Tensions remain high as US citizens defend both their neighbors and their own constitutional rights. Most recently, shocking footage of ICE using a 5-year-old boy as bait to trap other family members intensified calls to defund ICE. Public backlash also raged after videos showed ICE removing a US citizen from his home in his underwear. That arrest happened while ICE was conducting a warrantless search that a whistleblower warned is becoming the new ICE norm after an internal memo said that agents can enter homes without a judicial warrant.

Some politicians are starting to take up the call to diminish ICE’s power. On Thursday, the majority of House Democrats voted to defund ICE, which Politico noted was a “remarkable shift from when dozens of them voted to expand the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement authority just one year ago.” Of course, the ICE budget bill passed anyway, since Republicans control the House, but with public approval of ICE tanking, any ongoing pushback could hurt Republicans in midterms and eventually even doom ICE if momentum is sustained.

Students from St. Paul public schools protest at a massive walkout to the State Capitol in St. Paul, Minn., to protest ICE actions in Minnesota. Credit: Star Tribune via Getty Images / Contributor | Star Tribune

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has backed down from a fight to unmask the owners of Instagram and Facebook accounts monitoring Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activity in Pennsylvania.

One of the anonymous account holders, John Doe, sued to block ICE from identifying him and other critics online through summonses to Meta that he claimed infringed on core First Amendment-protected activity.

DHS initially fought Doe’s motion to quash the summonses, arguing that the community watch groups endangered ICE agents by posting “pictures and videos of agents’ faces, license plates, and weapons, among other things.” This was akin to “threatening ICE agents to impede the performance of their duties,” DHS alleged. DHS’s arguments echoed DHS Secretary Kristi Noem, who has claimed that identifying ICE agents is a crime, even though Wired noted that ICE employees often post easily discoverable LinkedIn profiles.

To Doe, the agency seemed intent on testing the waters to see if it could seize authority to unmask all critics online by invoking a customs statute that allows agents to subpoena information on goods entering or leaving the US.

But then, on January 16, DHS abruptly reversed course, withdrawing its summonses from Meta.

A court filing confirmed that DHS dropped its requests for subscriber information last week, after initially demanding Doe’s “postal code, country, all email address(es) on file, date of account creation, registered telephone numbers, IP address at account signup, and logs showing IP address and date stamps for account accesses.”

The filing does not explain why DHS decided to withdraw its requests.

However, previously, DHS requested similar information from Meta about six Instagram community watch groups that shared information about ICE activity in Los Angeles and other locations. DHS withdrew those requests, too, after account holders defended their First Amendment rights and filed motions to quash their summonses, Doe’s court filing said.

To defeat DHS’ summonses, Doe shared all his group’s online posts with the court. An attorney representing Doe at the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, Ariel Shapell, told Ars that Doe’s groups posted “pretty innocuous” content, like “information and resources about immigrant rights, due process rights, fundraising, and vigils.”

It’s possible DHS caved due to lack of evidence supporting claims that Doe’s groups’ posts carried implicit threats to “assault, kidnap, or murder any federal official,” as DHS had argued. But it’s also possible that DHS keeps trying and failing to unmask ICE critics due to strong First Amendment protections working to preserve the right to post anonymously online.

DHS faces spiking ICE criticism

The attempt to unmask Doe’s accounts came as criticism of ICE is mounting nationwide, and a win could have given ICE broad authority to attack that growing base of critics if DHS had dug in and its defense actually held.

DHS’s withdrawal of the summonses could signal that the argument the agency tried to raise—weirdly using a statute tied to the “importation/exportation of merchandise” to seize “unlimited subpoena authority” of ICE critics online—is clearly not a winning one.

Meta did not immediately respond to Ars’ request for comment. But Meta did play a role in challenging DHS’ summonses, initially by seeking more information from the agency and then notifying account holders to provide an opportunity to quash the summonses before information was shared.

So far, the playbook for community watch groups on Facebook and Instagram has been to follow Meta’s advice in order to block identifying information from being shared. But it remains unclear if Meta may have complied with DHS’s requests if account holders were not able to legally fight to quash them, perhaps leaving a vulnerable gray area for community watch groups.

For Doe and any others involved in “MontCo Community Watch,” DHS’s withdrawal of the summonses likely comes as a relief. But this wasn’t the first time DHS tried and failed to unmask online critics, so it’s just as likely that fears remain that DHS will continue trying to identify groups that are posting footage to raise awareness of ICE’s most controversial moves.

ICE critics have used footage of tragic events—like Renee Good’s killing and eight other ICE shootings since September—to support calls to remove ICE from embattled communities and abolish ICE.

Tensions remain high as US citizens defend both their neighbors and their own constitutional rights. Most recently, shocking footage of ICE using a 5-year-old boy as bait to trap other family members intensified calls to defund ICE. Public backlash also raged after videos showed ICE removing a US citizen from his home in his underwear. That arrest happened while ICE was conducting a warrantless search that a whistleblower warned is becoming the new ICE norm after an internal memo said that agents can enter homes without a judicial warrant.

Some politicians are starting to take up the call to diminish ICE’s power. On Thursday, the majority of House Democrats voted to defund ICE, which Politico noted was a “remarkable shift from when dozens of them voted to expand the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement authority just one year ago.” Of course, the ICE budget bill passed anyway, since Republicans control the House, but with public approval of ICE tanking, any ongoing pushback could hurt Republicans in midterms and eventually even doom ICE if momentum is sustained.