- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 830

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

Rice University chemists replicated Thomas Edison’s seminal experiment and found a surprising byproduct.

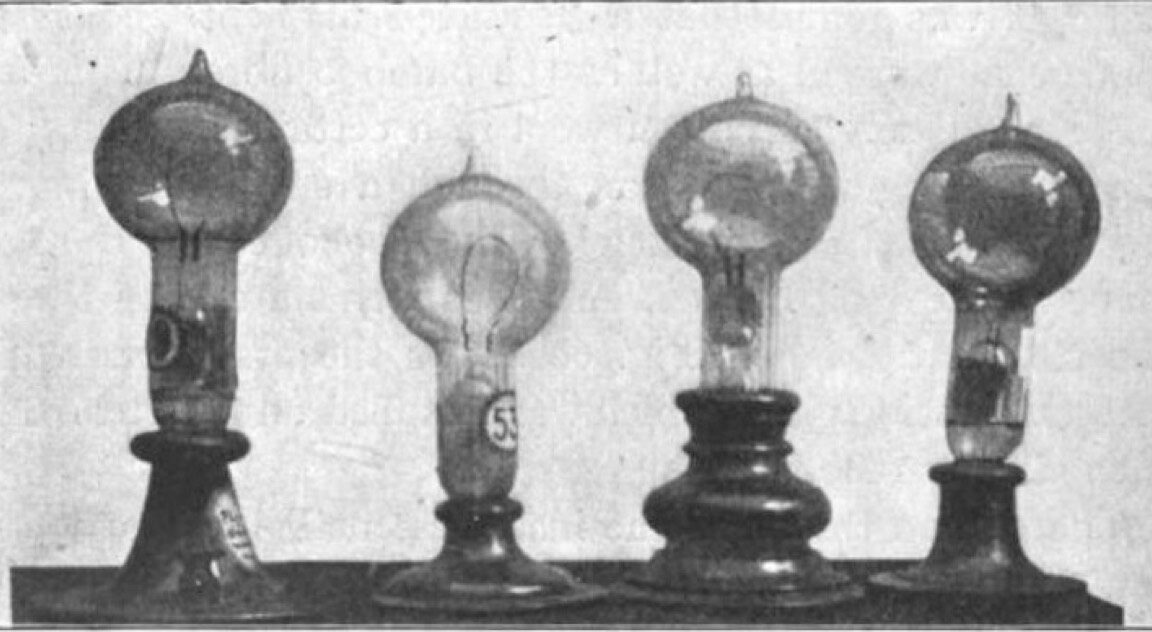

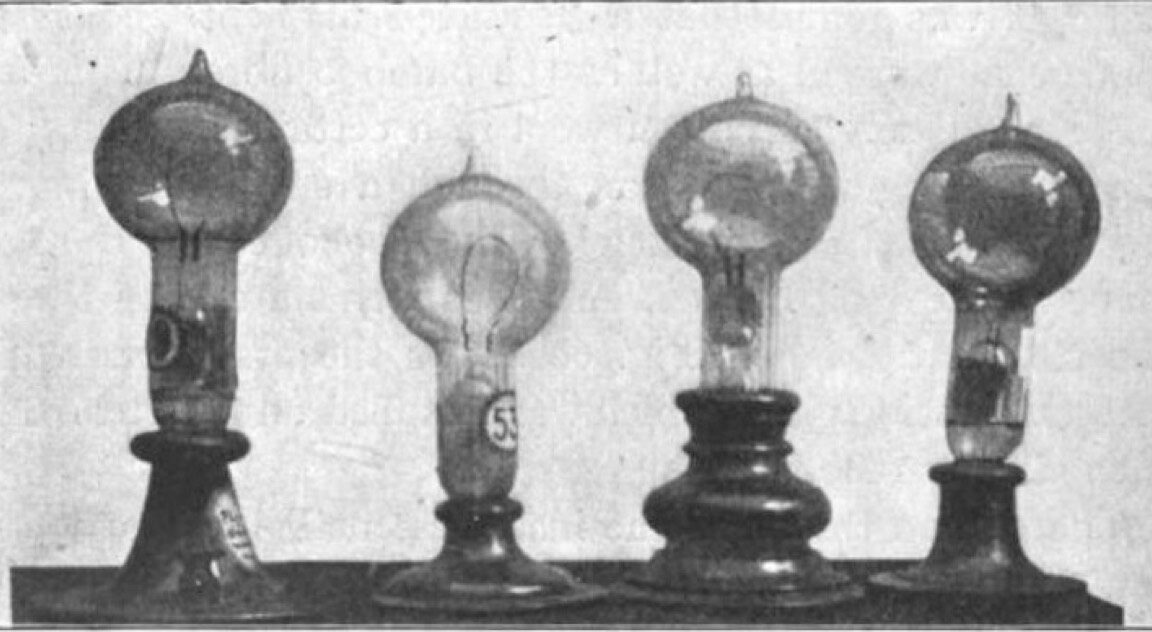

Edison carbon filament lamps, early 1880s Credit: Public domain

Graphene is the thinnest material yet known, composed of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. That structure gives it many unusual properties that hold great promise for real-world applications: batteries, super capacitors, antennas, water filters, transistors, solar cells, and touchscreens, just to name a few. The physicists who first synthesized graphene in the lab won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics. But 19th century inventor Thomas Edison may have unknowingly created graphene as a byproduct of his original experiments on incandescent bulbs over a century earlier, according to a new paper published in the journal ACS Nano.

“To reproduce what Thomas Edison did, with the tools and knowledge we have now, is very exciting,” said co-author James Tour, a chemist at Rice University. “Finding that he could have produced graphene inspires curiosity about what other information lies buried in historical experiments. What questions would our scientific forefathers ask if they could join us in the lab today? What questions can we answer when we revisit their work through a modern lens?”

Edison didn’t invent the concept of incandescent lamps; there were several versions predating his efforts. However, they generally had a a very short life span and required high electric current, so they weren’t well suited to Edison’s vision of large-scale commercialization. He experimented with different filament materials starting with carbonized cardboard and compressed lampblack. This, too, quickly burnt out, as did filaments made with various grasses and canes, like hemp and palmetto. Eventually Edison discovered that carbonized bamboo made for the best filament, with life spans over 1200 hours using a 110 volt power source.

Lucas Eddy, Tour’s grad student at Rice, was trying to figure out ways to mass produce graphene using the smallest, easiest equipment he could manage, with materials that were both affordable and readily available. He considered such options as arc welders and natural phenomena like lightning striking trees—both of which he admitted were “complete dead ends.” Edison’s light bulb, Eddy decided, would be ideal, since unlike other early light bulbs, Edison’s version was able to achieve the critical 2000 degree C temperatures required for flash Joule heating—the best method for making so-called turbostratic graphene.

Wizardry at Menlo Park

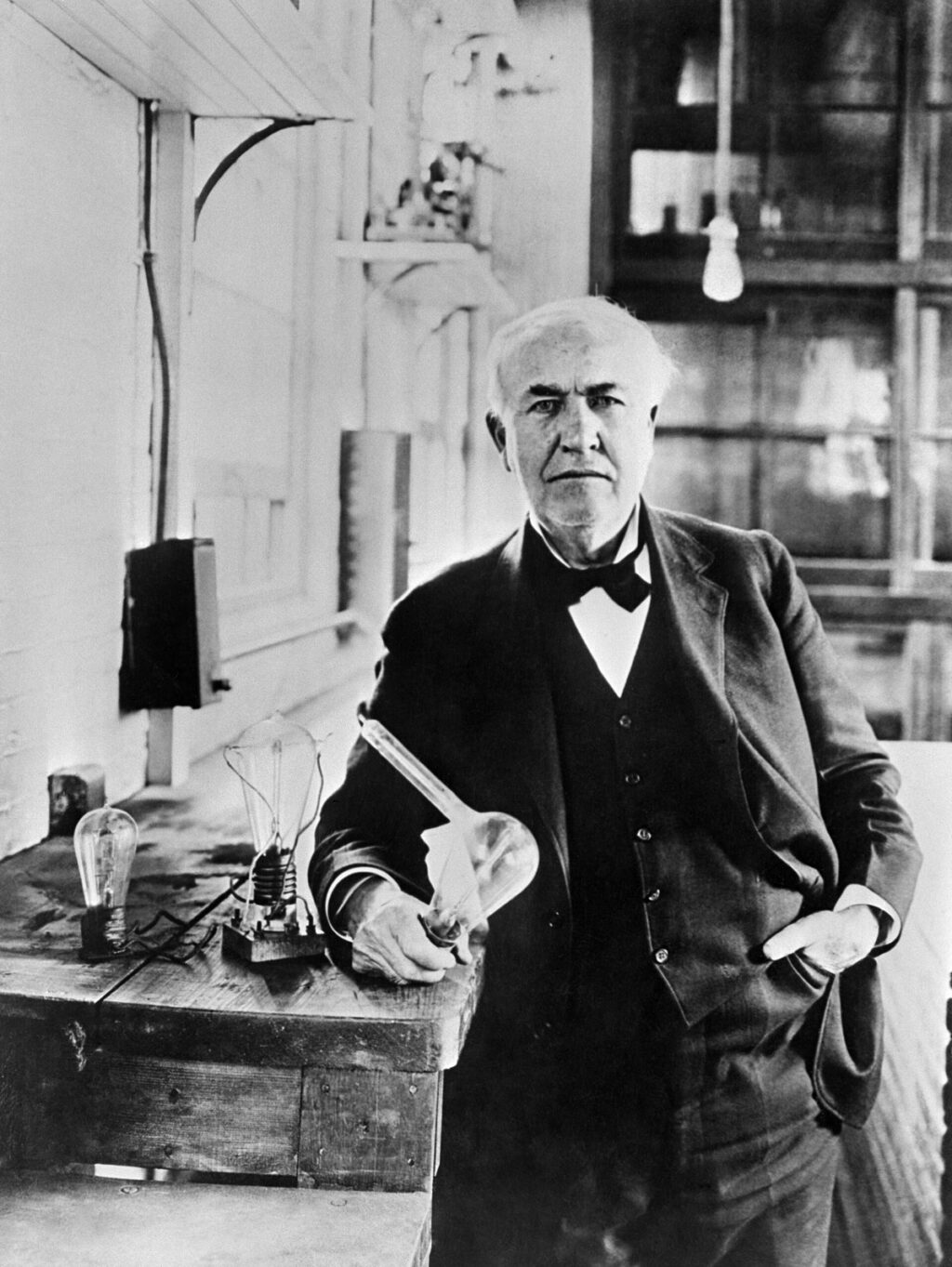

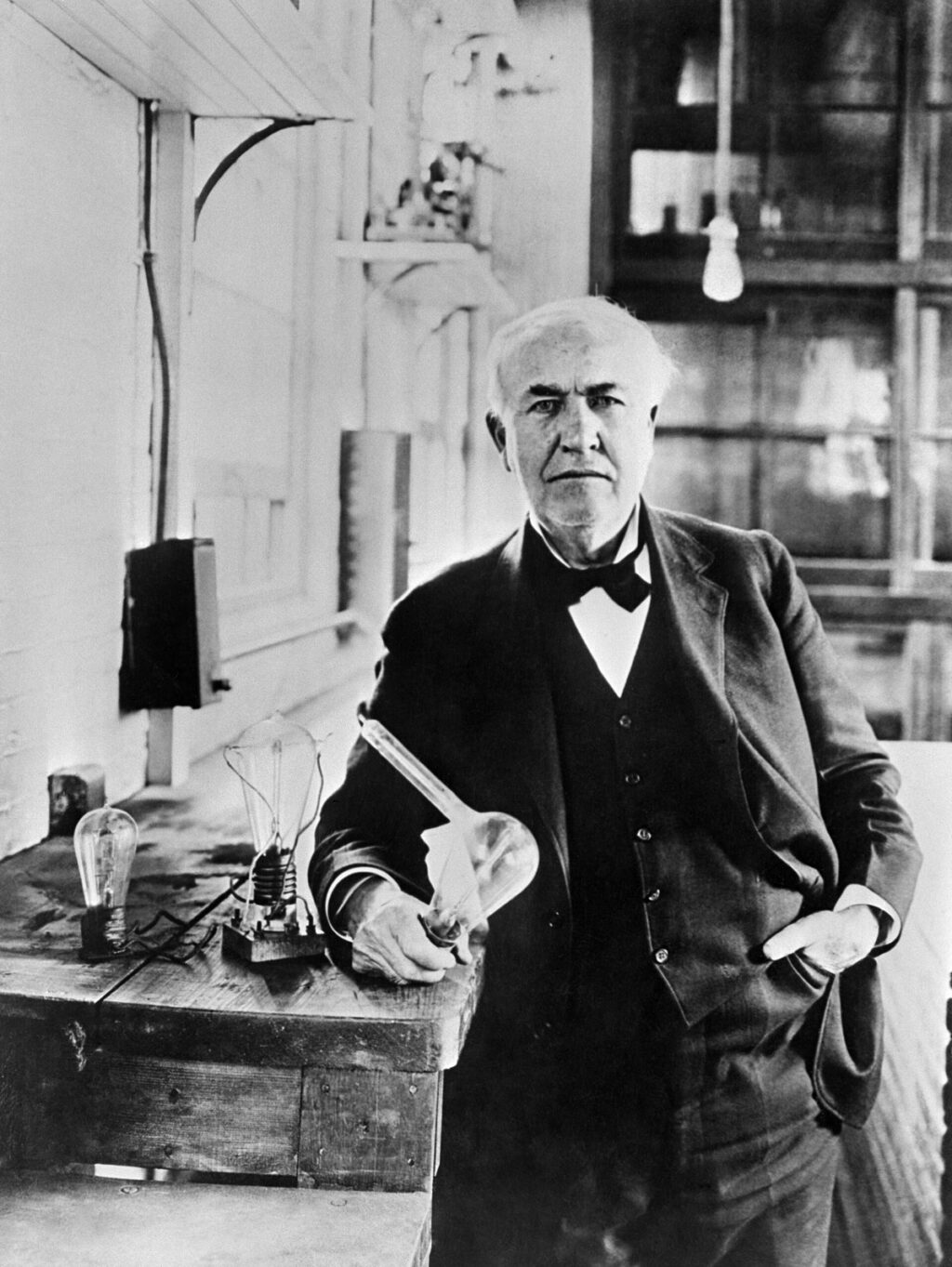

Thomas Edison with a light bulb from 1883. Public domain

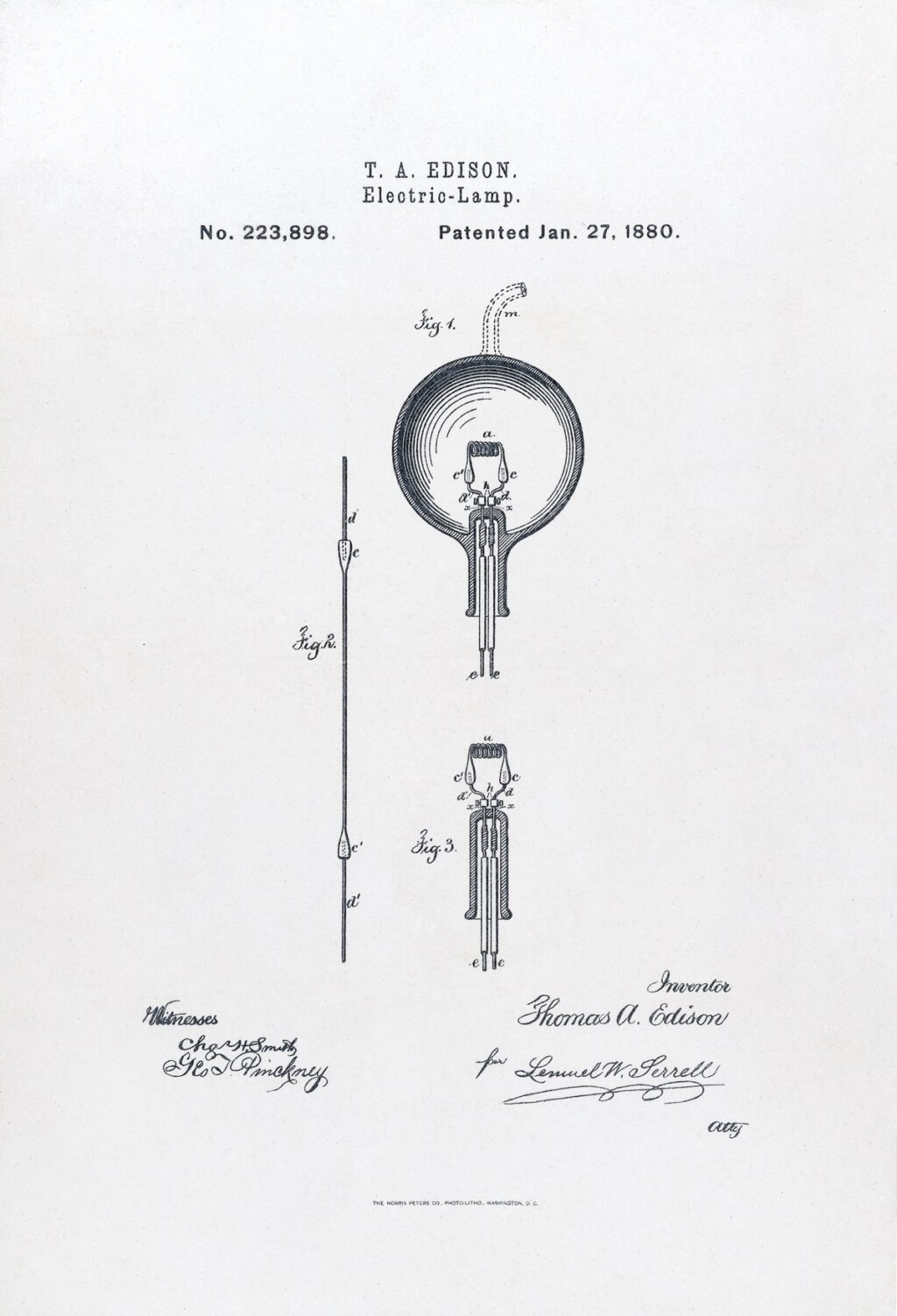

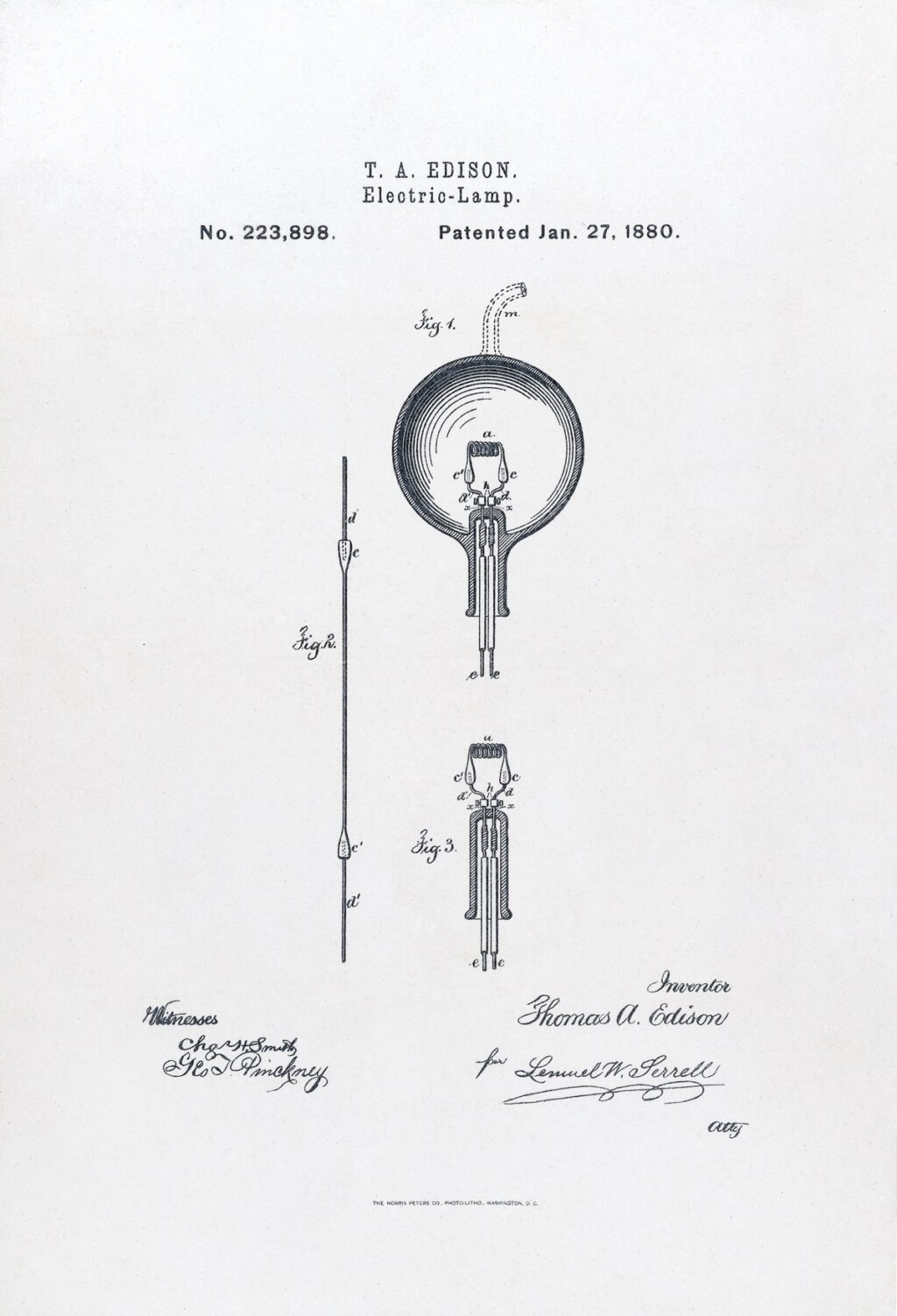

Edison’s U.S. Patent #223898: Electric-Lamp, issued January 27, 1880 Public domain

Thomas Edison with a light bulb from 1883. Public domain

Edison’s U.S. Patent #223898: Electric-Lamp, issued January 27, 1880 Public domain

Plus, Eddy had access to Edison’s original 1879 patent describing the invention process. Eddy recreated Edison’s experiment, attaching light bulbs to a 110-volt power source and switching it on for 20 seconds at a time to rapidly heat the carbon-based material to between 2000 to 3000 degrees C. (Switch it on for any longer and you get graphite rather than graphene.) Then he examined the results using a modern optical microscope.

His first attempt didn’t work out because the bulbs he bought turned out to use tungsten rather than carbon filaments. “You can’t fool a chemist,” said Eddy. “But I finally found a small art store in New York City selling artisan Edison-style light bulbs.” Those artisan bulbs used bamboo filaments, with diameters a mere 5 micrometers larger than Edison’s original filaments.

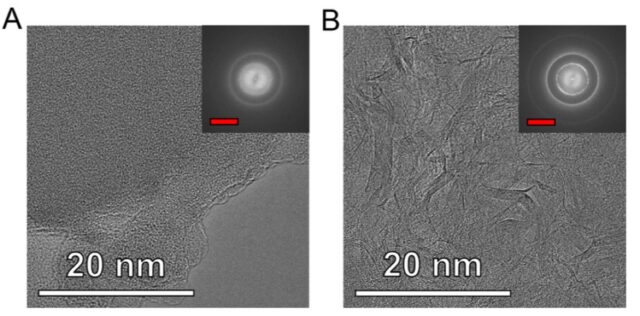

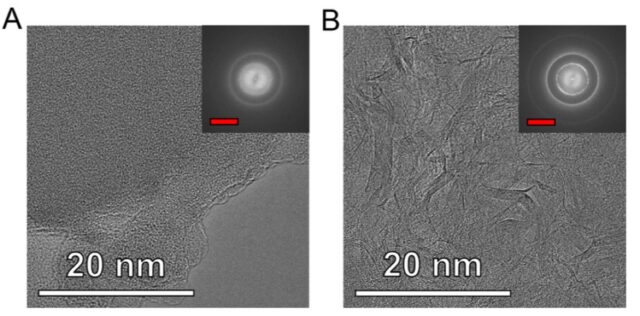

TEM image of the raw carbon filament before and after Joule heating. Distinct graphene layers are observed within the filament in (B), among some regions of unconverted amorphous carbon. Credit: Lucas Eddy et al., 2026

This time, Eddy noticed that the carbon filament turned to a “lustrous silver.” Raman spectroscopy revealed that parts of the filament had turned into turbostratic graphene. The team also took before and after images using transmission electron microscopy. Eddy and his co-authors acknowledge that this is not definitive proof that Edison produced graphene. The inventor lacked the means to detect it even if he had been aware that such a material existed. And even if one were to analyze Edison’s original bulb, any graphene would have long since turned into graphite.

The authors concluded by noting the research potential of revisiting other early technologies using the tools of modern materials science, such as vacuum tubes, arc lamps, and early X-ray tubes. These also may have accidentally produced unusual materials or reactions that weren’t analyzed or even noticed at the time. “Innovation can emerge from reinterpreting the past with fresh tools and new questions,” they wrote. “In the case of ‘Edison graphene,’ a 140-year-old invention continues to shed light not just literally but scientifically.”

DOI: ACS Nano, 2026. 10.1021/acsnano.5c12759 (About DOIs).

Edison carbon filament lamps, early 1880s Credit: Public domain

Graphene is the thinnest material yet known, composed of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. That structure gives it many unusual properties that hold great promise for real-world applications: batteries, super capacitors, antennas, water filters, transistors, solar cells, and touchscreens, just to name a few. The physicists who first synthesized graphene in the lab won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics. But 19th century inventor Thomas Edison may have unknowingly created graphene as a byproduct of his original experiments on incandescent bulbs over a century earlier, according to a new paper published in the journal ACS Nano.

“To reproduce what Thomas Edison did, with the tools and knowledge we have now, is very exciting,” said co-author James Tour, a chemist at Rice University. “Finding that he could have produced graphene inspires curiosity about what other information lies buried in historical experiments. What questions would our scientific forefathers ask if they could join us in the lab today? What questions can we answer when we revisit their work through a modern lens?”

Edison didn’t invent the concept of incandescent lamps; there were several versions predating his efforts. However, they generally had a a very short life span and required high electric current, so they weren’t well suited to Edison’s vision of large-scale commercialization. He experimented with different filament materials starting with carbonized cardboard and compressed lampblack. This, too, quickly burnt out, as did filaments made with various grasses and canes, like hemp and palmetto. Eventually Edison discovered that carbonized bamboo made for the best filament, with life spans over 1200 hours using a 110 volt power source.

Lucas Eddy, Tour’s grad student at Rice, was trying to figure out ways to mass produce graphene using the smallest, easiest equipment he could manage, with materials that were both affordable and readily available. He considered such options as arc welders and natural phenomena like lightning striking trees—both of which he admitted were “complete dead ends.” Edison’s light bulb, Eddy decided, would be ideal, since unlike other early light bulbs, Edison’s version was able to achieve the critical 2000 degree C temperatures required for flash Joule heating—the best method for making so-called turbostratic graphene.

Wizardry at Menlo Park

Thomas Edison with a light bulb from 1883. Public domain

Edison’s U.S. Patent #223898: Electric-Lamp, issued January 27, 1880 Public domain

Thomas Edison with a light bulb from 1883. Public domain

Edison’s U.S. Patent #223898: Electric-Lamp, issued January 27, 1880 Public domain

Plus, Eddy had access to Edison’s original 1879 patent describing the invention process. Eddy recreated Edison’s experiment, attaching light bulbs to a 110-volt power source and switching it on for 20 seconds at a time to rapidly heat the carbon-based material to between 2000 to 3000 degrees C. (Switch it on for any longer and you get graphite rather than graphene.) Then he examined the results using a modern optical microscope.

His first attempt didn’t work out because the bulbs he bought turned out to use tungsten rather than carbon filaments. “You can’t fool a chemist,” said Eddy. “But I finally found a small art store in New York City selling artisan Edison-style light bulbs.” Those artisan bulbs used bamboo filaments, with diameters a mere 5 micrometers larger than Edison’s original filaments.

TEM image of the raw carbon filament before and after Joule heating. Distinct graphene layers are observed within the filament in (B), among some regions of unconverted amorphous carbon. Credit: Lucas Eddy et al., 2026

This time, Eddy noticed that the carbon filament turned to a “lustrous silver.” Raman spectroscopy revealed that parts of the filament had turned into turbostratic graphene. The team also took before and after images using transmission electron microscopy. Eddy and his co-authors acknowledge that this is not definitive proof that Edison produced graphene. The inventor lacked the means to detect it even if he had been aware that such a material existed. And even if one were to analyze Edison’s original bulb, any graphene would have long since turned into graphite.

The authors concluded by noting the research potential of revisiting other early technologies using the tools of modern materials science, such as vacuum tubes, arc lamps, and early X-ray tubes. These also may have accidentally produced unusual materials or reactions that weren’t analyzed or even noticed at the time. “Innovation can emerge from reinterpreting the past with fresh tools and new questions,” they wrote. “In the case of ‘Edison graphene,’ a 140-year-old invention continues to shed light not just literally but scientifically.”

DOI: ACS Nano, 2026. 10.1021/acsnano.5c12759 (About DOIs).