- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 832

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

“I’ve got one job, and it’s the safe return of Reid, Victor, Christina, and Jeremy.”

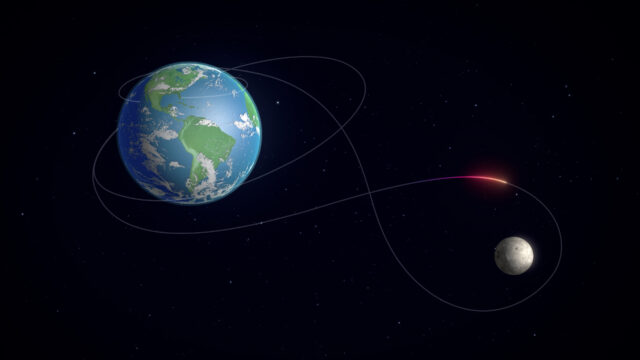

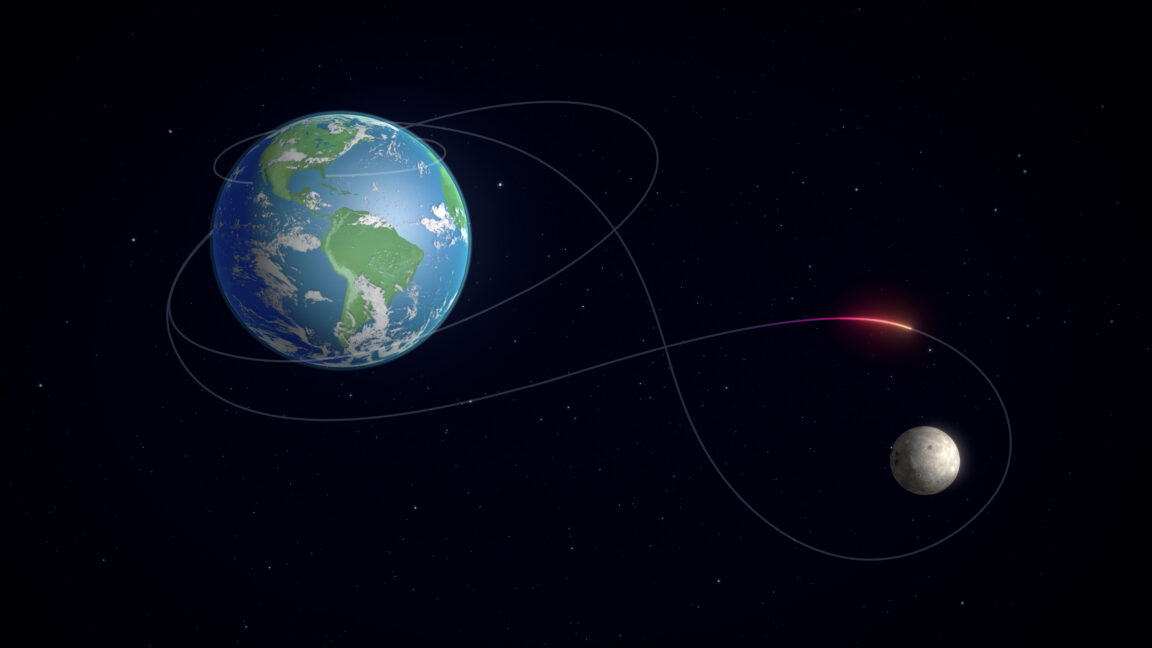

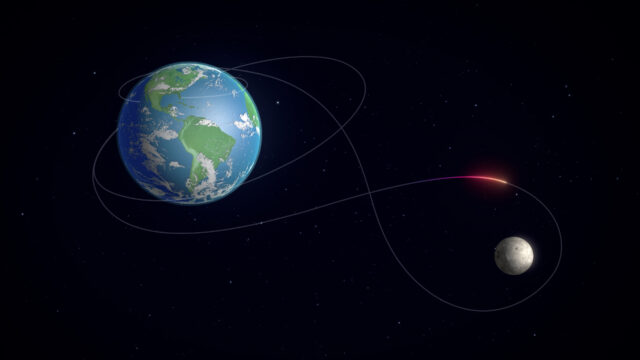

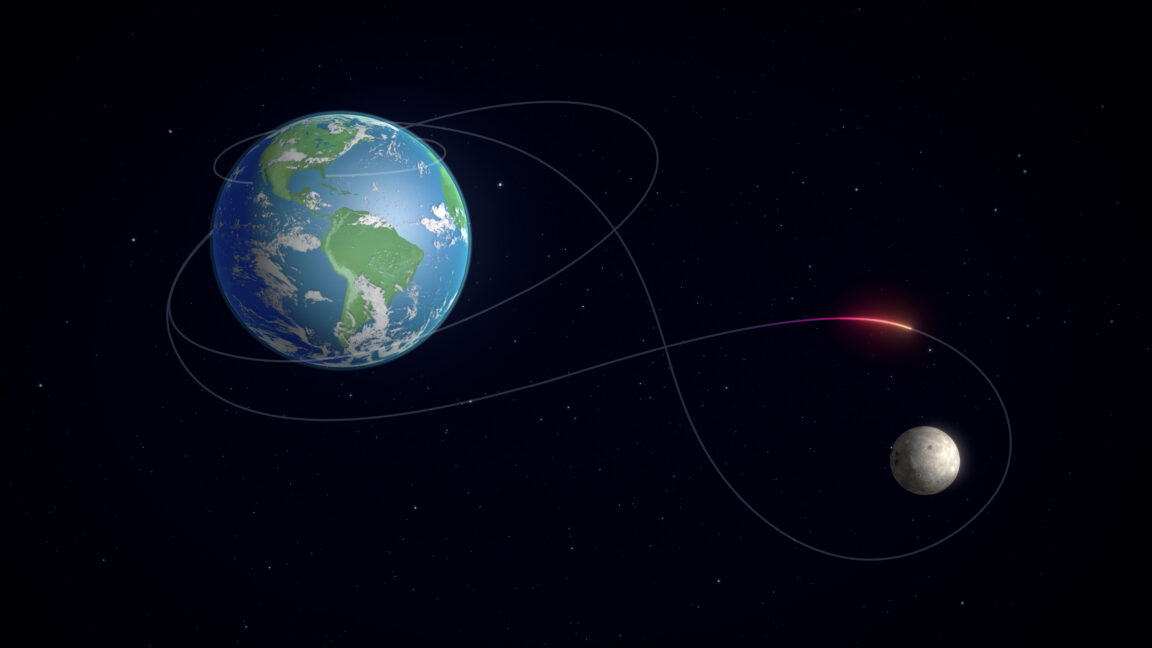

Artist's illustration of the Artemis II trajectory. Credit: NASA

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Florida—The rocket NASA is preparing to send four astronauts on a trip around the Moon will emerge from its assembly building on Florida’s Space Coast early Saturday for a slow crawl to its seaside launch pad.

Riding atop one of NASA’s diesel-powered crawler transporters, the Space Launch System rocket and its mobile launch platform will exit the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center around 7:00 am EST (11:00 UTC). The massive tracked transporter, certified by Guinness as the world’s heaviest self-propelled vehicle, is expected to cover the four miles between the assembly building and Launch Complex 39B in about eight to 10 hours.

The rollout marks a major step for NASA’s Artemis II mission, the first human voyage to the vicinity of the Moon since the last Apollo lunar landing in December 1972. Artemis II will not land. Instead, a crew of four astronauts will travel around the far side of the Moon at a distance of several thousand miles, setting the record for the farthest humans have ever ventured from Earth.

The flight will culminate with a scorching 25,000 mph (40,000 km per hour) reentry over the Pacific Ocean. The four Artemis II astronauts—NASA’s Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Canada’s Jeremy Hansen—will become the fastest humans in history, edging out a speed record set during the Apollo era of lunar exploration.

Origin story

The journey for the fully-assembled Moon rocket will begin early Saturday at a slower pace. After leaving the Vehicle Assembly Building, the moving 11 million-pound structure will head east, then make a left turn before climbing the ramp to Pad 39B overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

“We will be at a cruising speed of under one mile per hour,” said Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, NASA’s launch director for the Artemis II mission. “It’ll be a little slower around the turns and up the hill.”

The crawler carrying the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft was built 60 years ago to haul NASA’s Saturn V rockets, then kept around for the Space Shuttle Program. Now, the vehicle is back to its original purpose of positioning Moon-bound rockets on their launch pads.

“These are the kinds of days that we live for when you do the kind of work that we do,” said John Honeycutt, chair of NASA’s Mission Management Team for the Artemis II mission. “The rocket and the spacecraft, Orion Integrity, are getting ready to roll to the pad … It really doesn’t get much better than this, and we’re making history.”

You can watch live views of the rollout in this YouTube stream provided by NASA.

Artemis II is the first crew flight of NASA’s Artemis program, an initiative named for the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology. NASA named the program Artemis in 2019, but some of the building blocks have been around for 20 years.

NASA selected Orion contractor Lockheed Martin to oversee the development of a deep space capsule in 2006 as part of the George W. Bush administration’s soon-to-be canceled Constellation program. In 2011, a political bargain between the Obama administration and Congress revived the Orion program and kicked off development of the Space Launch System. The announcement of the Artemis program in 2019 leaned on work already underway on Orion and the SLS rocket as the centerpieces of an architecture to return US astronauts to the Moon.

Tens of billions of dollars later, everything is finally coming together for the final all-important milestone in developing the vehicles for transporting crews between the Earth and the Moon. A human-rated lunar lander and spacesuits tailored for Moonwalking astronauts are still a few years away from readiness. NASA has contracts with SpaceX and Blue Origin for landers, and with Axiom Space for suits.

A successful Artemis II mission would demonstrate to NASA’s managers and engineers that the Orion spacecraft and SLS rocket fulfill their roles in the Artemis architecture. NASA is expected to rely on the SLS rocket, which costs more than $2 billion per flight and is expendable by design, for several more missions until commercial alternatives are available.

America’s return to the Moon now has a geopolitical imperative. China is working to land its own astronauts on the lunar surface by 2030, and US officials want to beat the Chinese to the Moon for the motivation of national prestige and the material benefits of accessing lunar resources, among other reasons. For now, budget-writing lawmakers in Congress and President Donald Trump’s new NASA chief, Jared Isaacman, agree the existing SLS/Orion architecture, despite its cost and shortcomings, offers the surest opportunity to beat the Chinese space program to a crew lunar landing.

Then, if all goes according to plan, NASA can turn to cheaper (and in one case, more capable) rockets to help the government afford the expenditure required to construct a Moon base.

“Putting crew on the rocket and taking the crew around the Moon, this is going be our first step toward a sustained lunar presence,” Honeycutt said. “It’s 10 days [and] four astronauts going farther from Earth than any other human has ever traveled. We’ll be validating the Orion spacecraft’s life support, navigation and crew systems in the really harsh environments of deep space, and that’s going to pave the way for future landings.”

NASA’s 322-foot-tall (98-meter) SLS rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building on the eve of rollout to Launch Complex 39B. Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky

There is still much work ahead before NASA can clear Artemis II for launch. At the launch pad, technicians will complete final checkouts and closeouts before NASA’s launch team gathers in early February for a critical practice countdown. During this countdown, called a Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR), Blackwell-Thompson and her team will oversee the loading of the SLS rocket’s core stage and upper stage with super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants.

The cryogenic fluids, particularly liquid hydrogen, gave fits to the Artemis launch team as NASA prepared to launch the Artemis I mission—without astronauts—on the SLS rocket’s first test flight in 2022. Engineers resolved the issues and successfully launched the Artemis I mission in November 2022, and officials will apply the lessons for the Artemis II countdown.

“Artemis I was a test flight, and we learned a lot during that campaign getting to launch,” Blackwell-Thompson said. “And the things that we’ve learned relative to how to go load this vehicle, how to load LOX (liquid oxygen), how to load hydrogen, have all been rolled in to the way in which we intend to do for the Artemis II vehicle.”

Finding the right time to fly

Assuming the countdown rehearsal goes according to plan, NASA could be in a position to launch the Artemis II mission as soon as February 6. But the schedule for February 6 is tight, with no margin for error. Officials typically have about five days per month when they can launch Artemis II, when the Moon is in the right position relative to Earth, and the Orion spacecraft can follow the proper trajectory toward reentry and splashdown to limit stress on the capsule’s heat shield.

In February, the available launch dates are February 6, 7, 8, 10, and 11, with launch windows in the overnight hours in Florida. If the mission isn’t off the ground by February 11, NASA will have to stand down until a new series of launch opportunities beginning March 6. The space agency has posted a document showing all available launch dates and times through the end of April.

John Honeycutt, chair NASA’s Mission Management Team for the Artemis II mission, speaks during a news conference at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on January 16, 2026. Credit: Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

NASA’s leaders are eager for Artemis II to fly. NASA is not only racing China, a reality the agency’s former administrator acknowledged during the Biden administration. Now, the Trump administration is pushing NASA to accomplish a human landing on the Moon by the end of his presidential term on January 20, 2029.

One of Honeycutt’s jobs as chair of the Mission Management Team (MMT) is ensuring all the Is are dotted and Ts are crossed amid the frenzy of final launch preparations. While the hardware for Artemis II is on the move in Florida, the astronauts and flight controllers are wrapping up their final training and simulations at Johnson Space Center in Houston.

“I think I’ve got a good eye for launch fever,” he said Friday.

“As chair of the MMT, I’ve got one job, and it’s the safe return of Reid, Victor, Christina, and Jeremy. I consider that a duty and a trust, and it’s one I intend to see through.”

Artist's illustration of the Artemis II trajectory. Credit: NASA

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Florida—The rocket NASA is preparing to send four astronauts on a trip around the Moon will emerge from its assembly building on Florida’s Space Coast early Saturday for a slow crawl to its seaside launch pad.

Riding atop one of NASA’s diesel-powered crawler transporters, the Space Launch System rocket and its mobile launch platform will exit the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center around 7:00 am EST (11:00 UTC). The massive tracked transporter, certified by Guinness as the world’s heaviest self-propelled vehicle, is expected to cover the four miles between the assembly building and Launch Complex 39B in about eight to 10 hours.

The rollout marks a major step for NASA’s Artemis II mission, the first human voyage to the vicinity of the Moon since the last Apollo lunar landing in December 1972. Artemis II will not land. Instead, a crew of four astronauts will travel around the far side of the Moon at a distance of several thousand miles, setting the record for the farthest humans have ever ventured from Earth.

The flight will culminate with a scorching 25,000 mph (40,000 km per hour) reentry over the Pacific Ocean. The four Artemis II astronauts—NASA’s Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Canada’s Jeremy Hansen—will become the fastest humans in history, edging out a speed record set during the Apollo era of lunar exploration.

Origin story

The journey for the fully-assembled Moon rocket will begin early Saturday at a slower pace. After leaving the Vehicle Assembly Building, the moving 11 million-pound structure will head east, then make a left turn before climbing the ramp to Pad 39B overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

“We will be at a cruising speed of under one mile per hour,” said Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, NASA’s launch director for the Artemis II mission. “It’ll be a little slower around the turns and up the hill.”

The crawler carrying the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft was built 60 years ago to haul NASA’s Saturn V rockets, then kept around for the Space Shuttle Program. Now, the vehicle is back to its original purpose of positioning Moon-bound rockets on their launch pads.

“These are the kinds of days that we live for when you do the kind of work that we do,” said John Honeycutt, chair of NASA’s Mission Management Team for the Artemis II mission. “The rocket and the spacecraft, Orion Integrity, are getting ready to roll to the pad … It really doesn’t get much better than this, and we’re making history.”

You can watch live views of the rollout in this YouTube stream provided by NASA.

Artemis II is the first crew flight of NASA’s Artemis program, an initiative named for the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology. NASA named the program Artemis in 2019, but some of the building blocks have been around for 20 years.

NASA selected Orion contractor Lockheed Martin to oversee the development of a deep space capsule in 2006 as part of the George W. Bush administration’s soon-to-be canceled Constellation program. In 2011, a political bargain between the Obama administration and Congress revived the Orion program and kicked off development of the Space Launch System. The announcement of the Artemis program in 2019 leaned on work already underway on Orion and the SLS rocket as the centerpieces of an architecture to return US astronauts to the Moon.

Tens of billions of dollars later, everything is finally coming together for the final all-important milestone in developing the vehicles for transporting crews between the Earth and the Moon. A human-rated lunar lander and spacesuits tailored for Moonwalking astronauts are still a few years away from readiness. NASA has contracts with SpaceX and Blue Origin for landers, and with Axiom Space for suits.

A successful Artemis II mission would demonstrate to NASA’s managers and engineers that the Orion spacecraft and SLS rocket fulfill their roles in the Artemis architecture. NASA is expected to rely on the SLS rocket, which costs more than $2 billion per flight and is expendable by design, for several more missions until commercial alternatives are available.

America’s return to the Moon now has a geopolitical imperative. China is working to land its own astronauts on the lunar surface by 2030, and US officials want to beat the Chinese to the Moon for the motivation of national prestige and the material benefits of accessing lunar resources, among other reasons. For now, budget-writing lawmakers in Congress and President Donald Trump’s new NASA chief, Jared Isaacman, agree the existing SLS/Orion architecture, despite its cost and shortcomings, offers the surest opportunity to beat the Chinese space program to a crew lunar landing.

Then, if all goes according to plan, NASA can turn to cheaper (and in one case, more capable) rockets to help the government afford the expenditure required to construct a Moon base.

“Putting crew on the rocket and taking the crew around the Moon, this is going be our first step toward a sustained lunar presence,” Honeycutt said. “It’s 10 days [and] four astronauts going farther from Earth than any other human has ever traveled. We’ll be validating the Orion spacecraft’s life support, navigation and crew systems in the really harsh environments of deep space, and that’s going to pave the way for future landings.”

NASA’s 322-foot-tall (98-meter) SLS rocket inside the Vehicle Assembly Building on the eve of rollout to Launch Complex 39B. Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky

There is still much work ahead before NASA can clear Artemis II for launch. At the launch pad, technicians will complete final checkouts and closeouts before NASA’s launch team gathers in early February for a critical practice countdown. During this countdown, called a Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR), Blackwell-Thompson and her team will oversee the loading of the SLS rocket’s core stage and upper stage with super-cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants.

The cryogenic fluids, particularly liquid hydrogen, gave fits to the Artemis launch team as NASA prepared to launch the Artemis I mission—without astronauts—on the SLS rocket’s first test flight in 2022. Engineers resolved the issues and successfully launched the Artemis I mission in November 2022, and officials will apply the lessons for the Artemis II countdown.

“Artemis I was a test flight, and we learned a lot during that campaign getting to launch,” Blackwell-Thompson said. “And the things that we’ve learned relative to how to go load this vehicle, how to load LOX (liquid oxygen), how to load hydrogen, have all been rolled in to the way in which we intend to do for the Artemis II vehicle.”

Finding the right time to fly

Assuming the countdown rehearsal goes according to plan, NASA could be in a position to launch the Artemis II mission as soon as February 6. But the schedule for February 6 is tight, with no margin for error. Officials typically have about five days per month when they can launch Artemis II, when the Moon is in the right position relative to Earth, and the Orion spacecraft can follow the proper trajectory toward reentry and splashdown to limit stress on the capsule’s heat shield.

In February, the available launch dates are February 6, 7, 8, 10, and 11, with launch windows in the overnight hours in Florida. If the mission isn’t off the ground by February 11, NASA will have to stand down until a new series of launch opportunities beginning March 6. The space agency has posted a document showing all available launch dates and times through the end of April.

John Honeycutt, chair NASA’s Mission Management Team for the Artemis II mission, speaks during a news conference at Kennedy Space Center in Florida on January 16, 2026. Credit: Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images

NASA’s leaders are eager for Artemis II to fly. NASA is not only racing China, a reality the agency’s former administrator acknowledged during the Biden administration. Now, the Trump administration is pushing NASA to accomplish a human landing on the Moon by the end of his presidential term on January 20, 2029.

One of Honeycutt’s jobs as chair of the Mission Management Team (MMT) is ensuring all the Is are dotted and Ts are crossed amid the frenzy of final launch preparations. While the hardware for Artemis II is on the move in Florida, the astronauts and flight controllers are wrapping up their final training and simulations at Johnson Space Center in Houston.

“I think I’ve got a good eye for launch fever,” he said Friday.

“As chair of the MMT, I’ve got one job, and it’s the safe return of Reid, Victor, Christina, and Jeremy. I consider that a duty and a trust, and it’s one I intend to see through.”