- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 906

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

Bible Chat hits 30 million downloads as users seek algorithmic absolution.

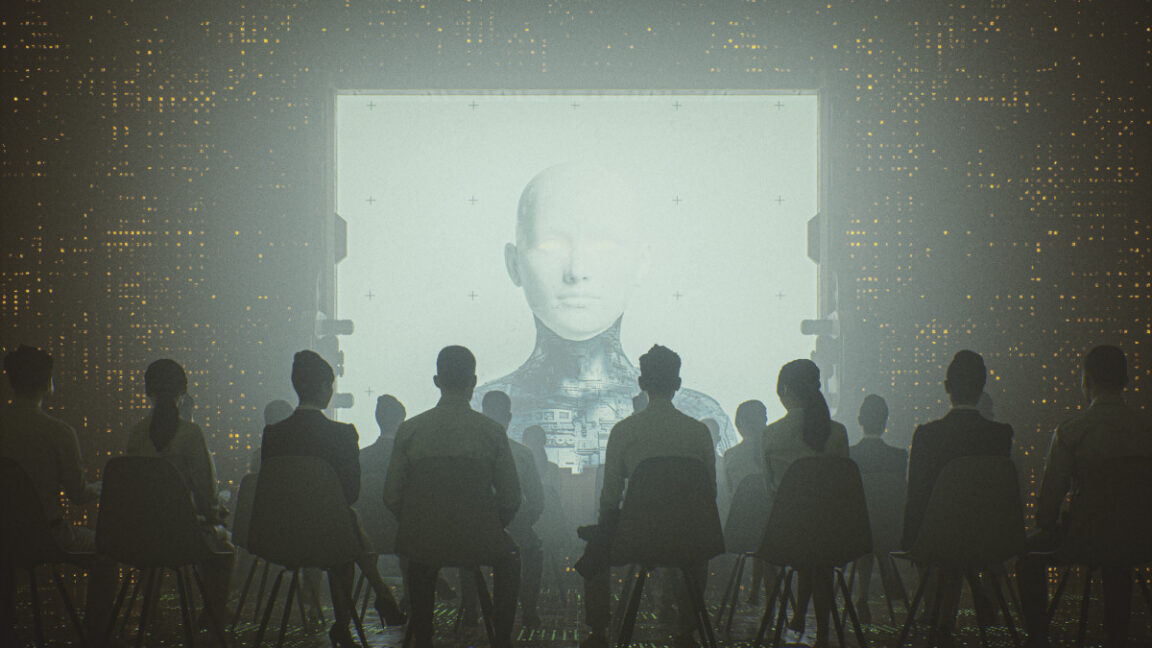

Credit: gremlin via Getty Images

On Sunday, The New York Times reported that tens of millions of people are confessing secrets to AI chatbots trained on religious texts, with apps like Bible Chat reaching over 30 million downloads and Catholic app Hallow briefly topping Netflix, Instagram, and TikTok in Apple's App Store. In China, people are using DeepSeek to try to decode their fortunes. In her report, Lauren Jackson examined "faith tech" apps that cost users up to $70 annually, with some platforms claiming to channel divine communication directly.

Some of the apps address what creators describe as an accessibility problem. "You don't want to disturb your pastor at three in the morning," Krista Rogers, a 61-year-old Ohio resident, told the Times about using the YouVersion Bible app and ChatGPT for spiritual questions.

The report also examines platforms that go beyond simple scriptural guidance. While a service like ChatwithGod operates as a "spiritual advisor," its conversational nature is convincing enough that users often question whether they are speaking directly with a divine being. As its chief executive told the Times, the most frequent question from users is, "Is this actually God I am talking to?"

The answer, of course, is no. These chatbots operate like other large language models—they generate statistically plausible text based on patterns in training data, not divine words from the heavens. When trained on religious texts, they produce responses that sound spiritually informed but can potentially mislead people with erroneous information or reassurance. Unlike human spiritual advisors, chatbots cannot have your best interests in mind because they don't have a mind: Chatbots are neither people nor supernatural beings.

The fusion of AI and religion isn't entirely new. In 2023, we reported on an experimental ChatGPT-powered church service at St. Paul's Church in Fürth, Germany, where over 300 attendees watched computer-generated avatars deliver a 40-minute sermon. Jonas Simmerlein, the theologian behind that event, framed it as learning to deal with AI's increasing presence in all aspects of life. But while that service was an intentional experiment with congregants aware they were hearing machine-generated text, today's faith tech apps blur the line between human spiritual guidance and algorithmic pattern matching, with millions of users potentially unaware of the distinction.

Theological yes-men

Many of these spiritual-flavored chatbots run on the same AI language models that run apps like ChatGPT and Gemini. While some companies train these models on religious texts and consult theologians about fine-tuning responses, it's widely known (and even admitted by the companies that make them) that these AI models trend toward outputs that validate users' feelings and ideas. If content-filtering safeguards fail, the tendency to affirm all ideas can lead to dangerous situations for vulnerable users.

"They're generally affirming. They are generally 'yes men,'" Ryan Beck, chief technology officer at Pray.com, told the Times. While this tendency, called "sycophancy" in the AI industry, has led to life-threatening problems with some users, Beck sees affirmation as beneficial. "Who doesn't need a little affirmation in their life?"

This validation tendency creates theological complications. Traditional faith practices often involve challenging believers to confront uncomfortable truths, but chatbots avoid this spiritual friction. Heidi Campbell, a Texas A&M professor who studies technology and religion, told The Times that chatbots "tell us what we want to hear," and "it's not using spiritual discernment, it is using data and patterns."

Privacy concerns compound these issues. "I wonder if there isn't a larger danger in pouring your heart out to a chatbot," Catholic priest Fr. Mike Schmitz told The Times. "Is it at some point going to become accessible to other people?" Users share intimate spiritual moments that now exist as data points in corporate servers.

Some users prefer the chatbots' non-judgmental responses to human religious communities. Delphine Collins, a 43-year-old Detroit preschool teacher, told the Times she found more support on Bible Chat than at her church after sharing her health struggles. "People stopped talking to me. It was horrible."

App creators maintain that their products supplement rather than replace human spiritual connection, and the apps arrive as approximately 40 million people have left US churches in recent decades. "They aren't going to church like they used to," Beck said. "But it's not that they're less inclined to find spiritual nourishment. It's just that they do it through different modes."

Different modes indeed. What faith-seeking users may not realize is that each chatbot response emerges fresh from the prompt you provide, with no permanent thread connecting one instance to the next beyond a rolling history of the present conversation and what might be stored as a "memory" in a separate system. When a religious chatbot says, "I'll pray for you," the simulated "I" making that promise ceases to exist the moment the response completes. There's no persistent identity to provide ongoing spiritual guidance, and no memory of your spiritual journey beyond what gets fed back into the prompt with every query.

But this is spirituality we're talking about, and despite technical realities, many people will believe that the chatbots can give them divine guidance. In matters of faith, contradictory evidence rarely shakes a strong belief once it takes hold, whether that faith is placed in the divine or in what are essentially voices emanating from a roll of loaded dice. For many, there may not be much difference.

Credit: gremlin via Getty Images

On Sunday, The New York Times reported that tens of millions of people are confessing secrets to AI chatbots trained on religious texts, with apps like Bible Chat reaching over 30 million downloads and Catholic app Hallow briefly topping Netflix, Instagram, and TikTok in Apple's App Store. In China, people are using DeepSeek to try to decode their fortunes. In her report, Lauren Jackson examined "faith tech" apps that cost users up to $70 annually, with some platforms claiming to channel divine communication directly.

Some of the apps address what creators describe as an accessibility problem. "You don't want to disturb your pastor at three in the morning," Krista Rogers, a 61-year-old Ohio resident, told the Times about using the YouVersion Bible app and ChatGPT for spiritual questions.

The report also examines platforms that go beyond simple scriptural guidance. While a service like ChatwithGod operates as a "spiritual advisor," its conversational nature is convincing enough that users often question whether they are speaking directly with a divine being. As its chief executive told the Times, the most frequent question from users is, "Is this actually God I am talking to?"

The answer, of course, is no. These chatbots operate like other large language models—they generate statistically plausible text based on patterns in training data, not divine words from the heavens. When trained on religious texts, they produce responses that sound spiritually informed but can potentially mislead people with erroneous information or reassurance. Unlike human spiritual advisors, chatbots cannot have your best interests in mind because they don't have a mind: Chatbots are neither people nor supernatural beings.

The fusion of AI and religion isn't entirely new. In 2023, we reported on an experimental ChatGPT-powered church service at St. Paul's Church in Fürth, Germany, where over 300 attendees watched computer-generated avatars deliver a 40-minute sermon. Jonas Simmerlein, the theologian behind that event, framed it as learning to deal with AI's increasing presence in all aspects of life. But while that service was an intentional experiment with congregants aware they were hearing machine-generated text, today's faith tech apps blur the line between human spiritual guidance and algorithmic pattern matching, with millions of users potentially unaware of the distinction.

Theological yes-men

Many of these spiritual-flavored chatbots run on the same AI language models that run apps like ChatGPT and Gemini. While some companies train these models on religious texts and consult theologians about fine-tuning responses, it's widely known (and even admitted by the companies that make them) that these AI models trend toward outputs that validate users' feelings and ideas. If content-filtering safeguards fail, the tendency to affirm all ideas can lead to dangerous situations for vulnerable users.

"They're generally affirming. They are generally 'yes men,'" Ryan Beck, chief technology officer at Pray.com, told the Times. While this tendency, called "sycophancy" in the AI industry, has led to life-threatening problems with some users, Beck sees affirmation as beneficial. "Who doesn't need a little affirmation in their life?"

This validation tendency creates theological complications. Traditional faith practices often involve challenging believers to confront uncomfortable truths, but chatbots avoid this spiritual friction. Heidi Campbell, a Texas A&M professor who studies technology and religion, told The Times that chatbots "tell us what we want to hear," and "it's not using spiritual discernment, it is using data and patterns."

Privacy concerns compound these issues. "I wonder if there isn't a larger danger in pouring your heart out to a chatbot," Catholic priest Fr. Mike Schmitz told The Times. "Is it at some point going to become accessible to other people?" Users share intimate spiritual moments that now exist as data points in corporate servers.

Some users prefer the chatbots' non-judgmental responses to human religious communities. Delphine Collins, a 43-year-old Detroit preschool teacher, told the Times she found more support on Bible Chat than at her church after sharing her health struggles. "People stopped talking to me. It was horrible."

App creators maintain that their products supplement rather than replace human spiritual connection, and the apps arrive as approximately 40 million people have left US churches in recent decades. "They aren't going to church like they used to," Beck said. "But it's not that they're less inclined to find spiritual nourishment. It's just that they do it through different modes."

Different modes indeed. What faith-seeking users may not realize is that each chatbot response emerges fresh from the prompt you provide, with no permanent thread connecting one instance to the next beyond a rolling history of the present conversation and what might be stored as a "memory" in a separate system. When a religious chatbot says, "I'll pray for you," the simulated "I" making that promise ceases to exist the moment the response completes. There's no persistent identity to provide ongoing spiritual guidance, and no memory of your spiritual journey beyond what gets fed back into the prompt with every query.

But this is spirituality we're talking about, and despite technical realities, many people will believe that the chatbots can give them divine guidance. In matters of faith, contradictory evidence rarely shakes a strong belief once it takes hold, whether that faith is placed in the divine or in what are essentially voices emanating from a roll of loaded dice. For many, there may not be much difference.