- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 917

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

Celebrated molecular biologist weathered late '80s controversy to become Caltech president.

Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore in 2021. Credit: Christopher Michel/CC BY-SA 4.0

Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist and former Caltech president David Baltimore—who found himself at the center of controversial allegations of fraud against a co-author—has died at 87 from cancer complications. He shared the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology for his work upending the then-consensus that cellular information flowed only in one direction. Baltimore is survived by his wife of 57 years, biologist Alice Huang, as well as a daughter and granddaughter.

"David Baltimore's contributions as a virologist, discerning fundamental mechanisms and applying those insights to immunology, to cancer, to AIDS, have transformed biology and medicine," current Caltech President Thomas F. Rosenbaum said in a statement. "David's profound influence as a mentor to generations of students and postdocs, his generosity as a colleague, his leadership of great scientific institutions, and his deep involvement in international efforts to define ethical boundaries for biological advances fill out an extraordinary intellectual life."

Baltimore was born in New York City in 1938. His father worked in the garment industry, and his mother later became a psychologist at the New School and Sarah Lawrence. Young David was academically precocious and decided he wanted to be a scientist after spending a high school summer learning about mouse genetics at the Jackson Laboratory in Maine. He graduated from Swarthmore College and earned his PhD in biology from Rockefeller University in 1964 with a thesis on the study of viruses in animal cells. He joined the Salk Institute in San Diego, married Huang, and moved to MIT in 1982, founding the Whitehead Institute.

Baltimore initially studied viruses like polio and mengovirus that make RNA copies of the RNA gnomes to replicate, but later turned his attention to retroviruses, which have enzymes that make DNA copies of viral RNA. He made a major breakthrough when he proved the existence of that viral enzyme, now known as reverse transcriptase. Previously scientists had thought that the flow of information went from DNA to RNA to protein synthesis. Baltimore showed that process could be reversed, ultimately enabling researchers to use disabled retroviruses to insert genes into human DNA to correct genetic diseases.

Longtime friend David Botstein was also a young MIT faculty member at the time and recalled Baltimore presenting his data at an informal evening seminar. "He gave this talk and I remember walking out of it and saying to [another faculty member], 'He is going to get the Nobel Prize for that,'" Botstein told The New York Times. Botstein's prediction came true in 1975. Baltimore shared the physiology prize with Howard Temin and Renato Dulbecco "for their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumor viruses and the genetic material of the cell."

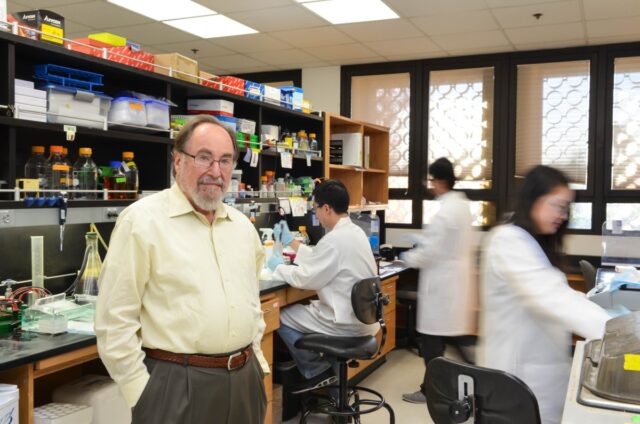

David Baltimore in his Caltech lab. Credit: Caltech

An affair to forget

Baltimore's stellar scientific reputation didn't prevent him from becoming embroiled in a scientific fraud investigation in the late 1980s, an earlier era of political hostility toward science. It was dubbed "the Baltimore affair" not because Baltimore himself was accused of scientific misconduct—the work wasn't even conducted in his lab—but because he co-authored the challenged study and strongly defended his co-author and MIT colleague, Thereza Imanishi-Kari, against the allegations.

The 1986 paper in question involved studying how the immune system rearranges genes to produce antibodies against new antigens. A postdoc in Imanishi-Kari's lab claimed she had been unable to replicate some of the experiments described in the paper and accused Imanishi-Kari of fabricating the data. Baltimore refused to retract it, and the postdoc dropped the challenge. But as the funding body, the National Institutes of Health felt compelled to investigate, while US Rep. John Dingell (D-Mich.) launched a series of congressional hearings on the subject. (Dingell was also involved in the investigation into Robert Gallo in the early 1990s over credit for the discovery of the AIDS virus.)

The investigation spanned several years and even involved the US Secret Service document examiners, who forensically analyzed Imanishi-Kari's lab notebooks right down to the ink. During that time, Baltimore left MIT to assume the presidency of Rockefeller University in 1989. When the NIH produced a draft report in 1991, it found Imanishi-Kari guilty of falsifying and fabricating data.

Naturally, the draft was leaked to the press, forcing a retraction. Baltimore apologized for not taking the original charge more seriously and resigned from his Rockefeller presidency, returning to MIT. Although there were no criminal or civil charges, in 1994 the NIH Office of Research Integrity pronounced Imanishi-Kari guilty on 19 counts of research misconduct, largely based on the USSS forensic analysis, and barred her from receiving federal grants for 10 years. She appealed and was fully exonerated in June 1996; she is now on the faculty of Tufts University.

As for Baltimore, he became Caltech president the following year but told The New York Times in 1996 that the controversy had taken its toll and that he couldn't bear to read coverage of the case. Yet he rebounded and focused on his work. Baltimore stepped down as Caltech president in 2006, but he continued to conduct research in his lab on viral vectors and mammalian immune systems, spending summers in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. He was among the scientists who in 2015 called for a global ban on using genome-editing techniques to alter human DNA.

While Baltimore is justly celebrated for his scientific achievements, Caltech economics professor emeritus Thomas Palfrey also praised Baltimore the man in a statement. "Everyone knows about [his science]," Palfrey said. "But what they probably don't know is how diverse and broad his interests were: music, classical, jazz, art, wine, exceptional food. He led a very multifaceted life, one of these people who put his foot on the accelerator and never let up his whole life. The amount of things that he did—traveling for pleasure and work—were mind-boggling. He cared about his friends, and he cared about the world. A lot of his work was trying to improve the human condition. He should be remembered for that."

Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore in 2021. Credit: Christopher Michel/CC BY-SA 4.0

Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist and former Caltech president David Baltimore—who found himself at the center of controversial allegations of fraud against a co-author—has died at 87 from cancer complications. He shared the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology for his work upending the then-consensus that cellular information flowed only in one direction. Baltimore is survived by his wife of 57 years, biologist Alice Huang, as well as a daughter and granddaughter.

"David Baltimore's contributions as a virologist, discerning fundamental mechanisms and applying those insights to immunology, to cancer, to AIDS, have transformed biology and medicine," current Caltech President Thomas F. Rosenbaum said in a statement. "David's profound influence as a mentor to generations of students and postdocs, his generosity as a colleague, his leadership of great scientific institutions, and his deep involvement in international efforts to define ethical boundaries for biological advances fill out an extraordinary intellectual life."

Baltimore was born in New York City in 1938. His father worked in the garment industry, and his mother later became a psychologist at the New School and Sarah Lawrence. Young David was academically precocious and decided he wanted to be a scientist after spending a high school summer learning about mouse genetics at the Jackson Laboratory in Maine. He graduated from Swarthmore College and earned his PhD in biology from Rockefeller University in 1964 with a thesis on the study of viruses in animal cells. He joined the Salk Institute in San Diego, married Huang, and moved to MIT in 1982, founding the Whitehead Institute.

Baltimore initially studied viruses like polio and mengovirus that make RNA copies of the RNA gnomes to replicate, but later turned his attention to retroviruses, which have enzymes that make DNA copies of viral RNA. He made a major breakthrough when he proved the existence of that viral enzyme, now known as reverse transcriptase. Previously scientists had thought that the flow of information went from DNA to RNA to protein synthesis. Baltimore showed that process could be reversed, ultimately enabling researchers to use disabled retroviruses to insert genes into human DNA to correct genetic diseases.

Longtime friend David Botstein was also a young MIT faculty member at the time and recalled Baltimore presenting his data at an informal evening seminar. "He gave this talk and I remember walking out of it and saying to [another faculty member], 'He is going to get the Nobel Prize for that,'" Botstein told The New York Times. Botstein's prediction came true in 1975. Baltimore shared the physiology prize with Howard Temin and Renato Dulbecco "for their discoveries concerning the interaction between tumor viruses and the genetic material of the cell."

David Baltimore in his Caltech lab. Credit: Caltech

An affair to forget

Baltimore's stellar scientific reputation didn't prevent him from becoming embroiled in a scientific fraud investigation in the late 1980s, an earlier era of political hostility toward science. It was dubbed "the Baltimore affair" not because Baltimore himself was accused of scientific misconduct—the work wasn't even conducted in his lab—but because he co-authored the challenged study and strongly defended his co-author and MIT colleague, Thereza Imanishi-Kari, against the allegations.

The 1986 paper in question involved studying how the immune system rearranges genes to produce antibodies against new antigens. A postdoc in Imanishi-Kari's lab claimed she had been unable to replicate some of the experiments described in the paper and accused Imanishi-Kari of fabricating the data. Baltimore refused to retract it, and the postdoc dropped the challenge. But as the funding body, the National Institutes of Health felt compelled to investigate, while US Rep. John Dingell (D-Mich.) launched a series of congressional hearings on the subject. (Dingell was also involved in the investigation into Robert Gallo in the early 1990s over credit for the discovery of the AIDS virus.)

The investigation spanned several years and even involved the US Secret Service document examiners, who forensically analyzed Imanishi-Kari's lab notebooks right down to the ink. During that time, Baltimore left MIT to assume the presidency of Rockefeller University in 1989. When the NIH produced a draft report in 1991, it found Imanishi-Kari guilty of falsifying and fabricating data.

Naturally, the draft was leaked to the press, forcing a retraction. Baltimore apologized for not taking the original charge more seriously and resigned from his Rockefeller presidency, returning to MIT. Although there were no criminal or civil charges, in 1994 the NIH Office of Research Integrity pronounced Imanishi-Kari guilty on 19 counts of research misconduct, largely based on the USSS forensic analysis, and barred her from receiving federal grants for 10 years. She appealed and was fully exonerated in June 1996; she is now on the faculty of Tufts University.

As for Baltimore, he became Caltech president the following year but told The New York Times in 1996 that the controversy had taken its toll and that he couldn't bear to read coverage of the case. Yet he rebounded and focused on his work. Baltimore stepped down as Caltech president in 2006, but he continued to conduct research in his lab on viral vectors and mammalian immune systems, spending summers in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. He was among the scientists who in 2015 called for a global ban on using genome-editing techniques to alter human DNA.

While Baltimore is justly celebrated for his scientific achievements, Caltech economics professor emeritus Thomas Palfrey also praised Baltimore the man in a statement. "Everyone knows about [his science]," Palfrey said. "But what they probably don't know is how diverse and broad his interests were: music, classical, jazz, art, wine, exceptional food. He led a very multifaceted life, one of these people who put his foot on the accelerator and never let up his whole life. The amount of things that he did—traveling for pleasure and work—were mind-boggling. He cared about his friends, and he cared about the world. A lot of his work was trying to improve the human condition. He should be remembered for that."