- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 917

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

"It was over quickly for both males, one after the other. The first took 63 seconds, the other 47."

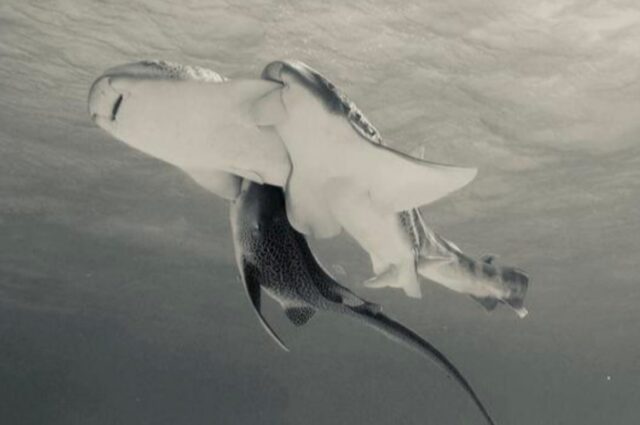

Three leopard sharks in rare mating sequence Credit: Hugo Lassauce-UniSC-Aquarium des Lagos

It's a rare occurrence for scientists to witness sharks mating in the wild. It's even rarer to catch three leopard sharks—two males and one female—engaging in what amounts to a threesome in the wild on camera, particularly since they are considered an endangered species. But that's just what one enterprising marine biology team achieved, describing the mating sequence in careful, clinical detail in a paper published in the Journal of Ethology.

It's not like scientists don't know anything about leopard shark mating behavior; rather, most of that knowledge comes from studying the sharks in captivity. Whether the behavior is identical in the wild is an open question because there hadn't been any documented observations of leopard shark mating practices in the wild—until now.

Hugo Lassauce, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of the Sunshine Coast (UniSC) in Australia, was working with the Aquarium des Lagons in Nouméa, New Caledonia, to monitor sharks off the coast of that South Pacific territory. Lassauce has been snorkeling daily with sharks for a year as part of that program—always with an accompanying boat for safety purposes—and had seen bits of the leopard shark mating behavior before, but never the entire sequence. Then he spotted a female shark on the sand below with two males hanging onto her pectoral fins—classic pre-copulation (courtship) behavior observed in captive leopard sharks.

“I told my colleague to take the boat away to avoid disturbance, and I started waiting on the surface, looking down at the sharks almost motionless on the sea floor," said Lassauce. “I waited an hour, freezing in the water, but finally they started swimming up. It was over quickly for both males, one after the other. The first took 63 seconds, the other 47. Then the males lost all their energy and lay immobile on the bottom while the female swam away actively.” (Add your own salacious jokes here. You know you're thinking them.)

Three sharks, two cameras

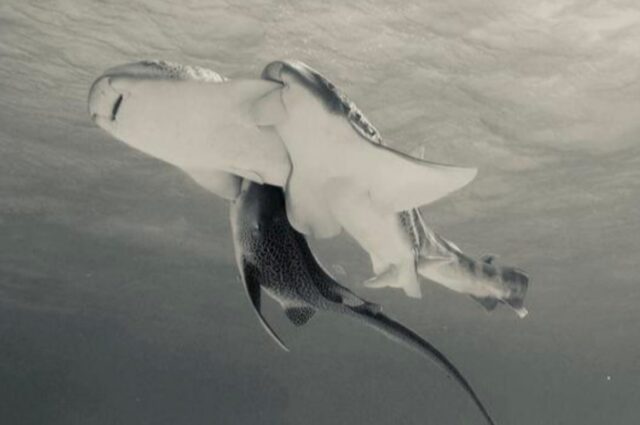

Moving the action closer to the surface. Credit: Hugo Lassauce/UniSC-Aquarium des Lagons

Lassauce had two GoPro Hero 5 cameras ready at hand, albeit with questionable battery life. That's why the video footage has two interruptions to the action: once when he had to switch cameras after getting a "low battery" signal, and a second time when he voluntarily stopped filming to conserve the second camera's battery. Not much happened for 55 minutes, after all, and he wanted to be sure to capture the pivotal moments in the sequence. Lassauce succeeded and was rewarded with triumphant cheers from his fellow marine biologists on the boat, who knew full well the rarity of what had just been documented for posterity.

The lengthy pre-copulation stage involved all three sharks motionless on the seafloor for nearly an hour, after which the female started swimming with one male shark biting onto each of her pectoral fins. A few minutes later, the first male made his move, "penetrating the female's cloaca with his left clasper." Claspers are modified pelvic fins capable of transferring sperm. After the first male shark finished, he lay motionless while the second male held onto the female's other fin. Then the other shark moved in, did his business, went motionless, and the female shark swam away. The males also swam away soon afterward.

Apart from the scientific first, documenting the sequence is a good indicator that this particular area is a critical mating habitat for leopard sharks, and could lead to better conservation strategies, as well as artificial insemination efforts to "rewild" leopard sharks in Australia and several other countries. “It’s surprising and fascinating that two males were involved sequentially on this occasion,” said co-author Christine Dudgeon, also of UniSC, adding, “From a genetic diversity perspective, we want to find out how many fathers contribute to the batches of eggs laid each year by females.”

Journal of Ethology, 2025. DOI: 10.1007/s10164-025-00866-4 (About DOIs).

Three leopard sharks in rare mating sequence Credit: Hugo Lassauce-UniSC-Aquarium des Lagos

It's a rare occurrence for scientists to witness sharks mating in the wild. It's even rarer to catch three leopard sharks—two males and one female—engaging in what amounts to a threesome in the wild on camera, particularly since they are considered an endangered species. But that's just what one enterprising marine biology team achieved, describing the mating sequence in careful, clinical detail in a paper published in the Journal of Ethology.

It's not like scientists don't know anything about leopard shark mating behavior; rather, most of that knowledge comes from studying the sharks in captivity. Whether the behavior is identical in the wild is an open question because there hadn't been any documented observations of leopard shark mating practices in the wild—until now.

Hugo Lassauce, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of the Sunshine Coast (UniSC) in Australia, was working with the Aquarium des Lagons in Nouméa, New Caledonia, to monitor sharks off the coast of that South Pacific territory. Lassauce has been snorkeling daily with sharks for a year as part of that program—always with an accompanying boat for safety purposes—and had seen bits of the leopard shark mating behavior before, but never the entire sequence. Then he spotted a female shark on the sand below with two males hanging onto her pectoral fins—classic pre-copulation (courtship) behavior observed in captive leopard sharks.

“I told my colleague to take the boat away to avoid disturbance, and I started waiting on the surface, looking down at the sharks almost motionless on the sea floor," said Lassauce. “I waited an hour, freezing in the water, but finally they started swimming up. It was over quickly for both males, one after the other. The first took 63 seconds, the other 47. Then the males lost all their energy and lay immobile on the bottom while the female swam away actively.” (Add your own salacious jokes here. You know you're thinking them.)

Three sharks, two cameras

Moving the action closer to the surface. Credit: Hugo Lassauce/UniSC-Aquarium des Lagons

Lassauce had two GoPro Hero 5 cameras ready at hand, albeit with questionable battery life. That's why the video footage has two interruptions to the action: once when he had to switch cameras after getting a "low battery" signal, and a second time when he voluntarily stopped filming to conserve the second camera's battery. Not much happened for 55 minutes, after all, and he wanted to be sure to capture the pivotal moments in the sequence. Lassauce succeeded and was rewarded with triumphant cheers from his fellow marine biologists on the boat, who knew full well the rarity of what had just been documented for posterity.

The lengthy pre-copulation stage involved all three sharks motionless on the seafloor for nearly an hour, after which the female started swimming with one male shark biting onto each of her pectoral fins. A few minutes later, the first male made his move, "penetrating the female's cloaca with his left clasper." Claspers are modified pelvic fins capable of transferring sperm. After the first male shark finished, he lay motionless while the second male held onto the female's other fin. Then the other shark moved in, did his business, went motionless, and the female shark swam away. The males also swam away soon afterward.

Apart from the scientific first, documenting the sequence is a good indicator that this particular area is a critical mating habitat for leopard sharks, and could lead to better conservation strategies, as well as artificial insemination efforts to "rewild" leopard sharks in Australia and several other countries. “It’s surprising and fascinating that two males were involved sequentially on this occasion,” said co-author Christine Dudgeon, also of UniSC, adding, “From a genetic diversity perspective, we want to find out how many fathers contribute to the batches of eggs laid each year by females.”

Journal of Ethology, 2025. DOI: 10.1007/s10164-025-00866-4 (About DOIs).