- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 917

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

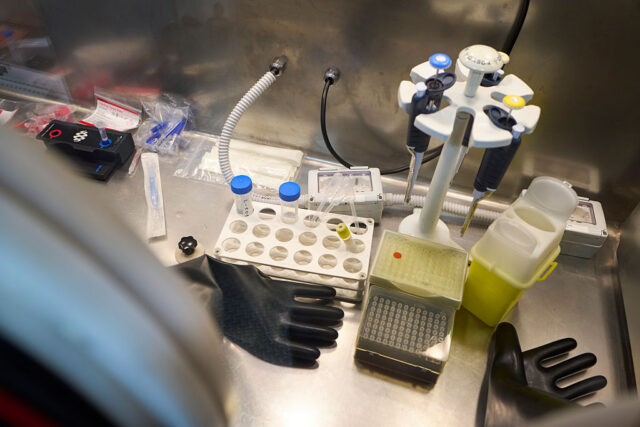

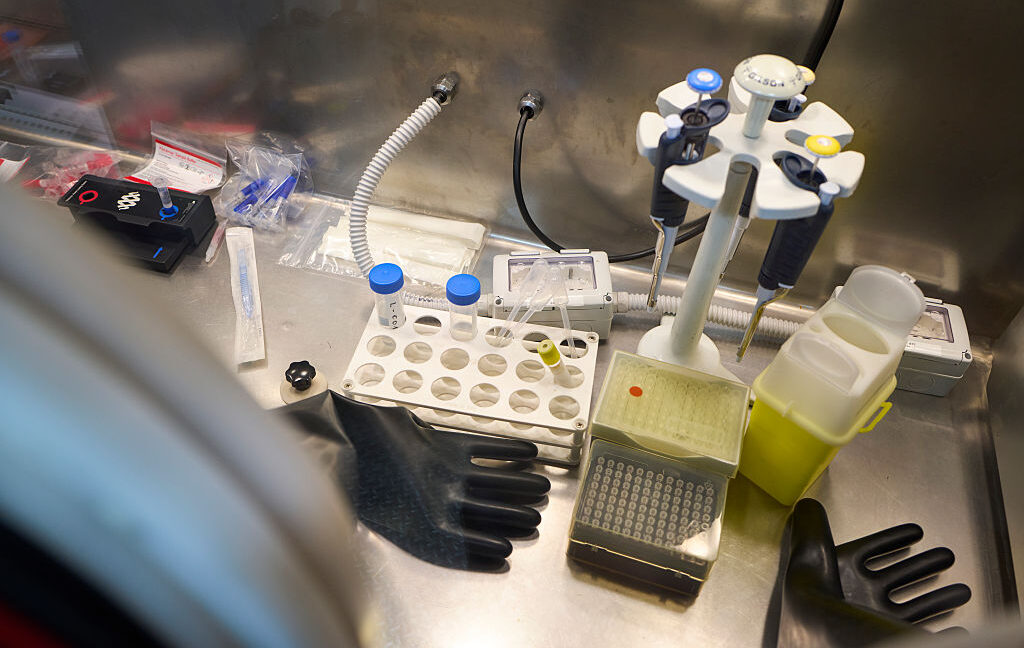

Drug patents frequently cite research that the NIH wouldn't be able to fund.

Credit: NurPhoto

The proposed federal budget would see drastic cuts made to most of the agencies that fund science. The sheer magnitude of the cuts—including a 40 percent slashing of money going to the National Institutes of Health—would do severe harm to biomedical researchers and the industries that serve or rely on them. And, ultimately, that is likely to do harm to all of us.

In today's issue of Science, some researchers have attempted to put numbers on those indirect effects that fall within that "ultimately" category. They've identified which grants wouldn't have been funded had similar cuts been made earlier in this century and tracked the impact that likely had on drug patents. Their conclusion: Development of roughly half the newly approved drugs relied on work that was funded by a grant that would need to be cut.

From grants to drugs

It's uncertain whether the proposed budget cuts will go through. At the moment, Congress is looking to fund most science agencies at levels similar to their current budgets. Should cuts eventually happen, then it's also difficult to predict how they'll be spread among the more than 20 institutes that make up the NIH (a number that the administration also wants to see reduced via consolidation). So, the researchers make a big simplifying assumption: Every institute within the NIH will take a 40 percent hit to its budget.

From there, it actually becomes simple to identify the grants that would be dropped as a result of these budget cuts. That's because the NIH operates a system in which each grant submission gets a priority score after evaluation and discussion. Grants are then funded, starting from the top-scoring grant and proceeding down the list, until the budget is exhausted. In this case, one of the researchers had access to every priority score between 1980 and 2007. So, the team simply started with the same list but a 40 percent smaller budget, making it easy to identify the grants that were funded based on the actual budget, but wouldn't have been after a 40 percent cut.

It's possible that some of the work funded by these "at risk" grants would have been done regardless. But the NIH is the largest supporter of biomedical research on the planet, so there aren't a ton of other options out there.

In any case, the researchers decided to look at the impact of the work funded by at-risk grants. Again, there are plenty of ways to judge impact: the patents arising from the work, the number of times papers funded by the grant were cited, and so on. However, the researchers decided to focus on the societal impact using one of the key outcomes of biomedical research: drugs.

Tracing that pathway is also surprisingly easy. The law that governs patenting of federally funded research requires that researchers report any patents arising from research back to the federal government. In addition, patents themselves allow the citation of scientific publications, which can also be traced back to grants.

So, the team started with the 557 drugs that have been approved between 2000 and 2023 and looked at the relevant patents, focusing on the ones issued prior to a drug's approval. Those patents were checked for citations of NIH-funded research or direct filings with the government.

From paper to patent

The simplest test is how many of them directly acknowledge support from an at-risk grant. That turned out to be 14, or 2.5 percent. While that number seems low, only 7 percent of the drugs in total directly acknowledged NIH support, so the at-risk grants represent a substantial proportion of that.

But it's also a somewhat unrealistic measure. Just about anything you do in biology now is based on decades of work done elsewhere, some of which may be absolutely essential to the final piece of research that led to the patent. That sort of intellectual contribution is likely to show up as a citation, rather than a direct acknowledgement. So, the researchers next focused on those citations.

It turns out that nearly 60 percent of the patents cite NIH-funded research. And here, the at-risk grants put in a very good showing, with just over half of the patents citing at least one at-risk grant. Note that many grants will have citations from both categories; to get a better sense, the researchers looked for patents where at least a quarter of the papers cited arose from NIH-funded research. For any grant, that number was a bit over 35 percent; for at-risk grants, it was about 12 percent.

Looking at specific examples, the researchers found that some of the approved drugs that relied on at-risk research were used for cancer treatments and genetic disorders. In other words, treatments that are likely to have a significant impact on public health. There are a couple of reasons to think that this is an underestimation of the impact, as well. To begin with, their source data on funding priorities stops at 2007, leaving a roughly 15-year gap where research funding can't be analyzed, but patents are still being filed.

In addition, drugs are just a small part of the potential impact of NIH research. "We excluded a wide range of important medical advances that may also build on NIH-funded research," the researchers acknowledge. "These include vaccines, gene and cell therapies, and other biologic drugs; diagnostic technologies and medical devices; as well as innovations in medical procedures, patient care practices, and surgical techniques." Beyond the obvious implications for public health, these sorts of patents can result in lots of economic activity, including the launching of entirely new businesses.

Beyond informing current debates about science funding, the research makes a larger point about scientific progress. We tend to focus on the major leaps forward and the high-profile scientists that drive them, as the upcoming Nobel Prizes highlight. But the reality is that most advances, especially in biology, are built on a broad intellectual foundation of lower-profile work that may require years for someone to find a way to apply it to anything patentable. Broad cuts like these may mean that the scientific superstars will still walk away with grants, while leaving a field devastated by having parts of this foundation knocked out from under it.

Science, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/science.aeb1564 (About DOIs).

Credit: NurPhoto

The proposed federal budget would see drastic cuts made to most of the agencies that fund science. The sheer magnitude of the cuts—including a 40 percent slashing of money going to the National Institutes of Health—would do severe harm to biomedical researchers and the industries that serve or rely on them. And, ultimately, that is likely to do harm to all of us.

In today's issue of Science, some researchers have attempted to put numbers on those indirect effects that fall within that "ultimately" category. They've identified which grants wouldn't have been funded had similar cuts been made earlier in this century and tracked the impact that likely had on drug patents. Their conclusion: Development of roughly half the newly approved drugs relied on work that was funded by a grant that would need to be cut.

From grants to drugs

It's uncertain whether the proposed budget cuts will go through. At the moment, Congress is looking to fund most science agencies at levels similar to their current budgets. Should cuts eventually happen, then it's also difficult to predict how they'll be spread among the more than 20 institutes that make up the NIH (a number that the administration also wants to see reduced via consolidation). So, the researchers make a big simplifying assumption: Every institute within the NIH will take a 40 percent hit to its budget.

From there, it actually becomes simple to identify the grants that would be dropped as a result of these budget cuts. That's because the NIH operates a system in which each grant submission gets a priority score after evaluation and discussion. Grants are then funded, starting from the top-scoring grant and proceeding down the list, until the budget is exhausted. In this case, one of the researchers had access to every priority score between 1980 and 2007. So, the team simply started with the same list but a 40 percent smaller budget, making it easy to identify the grants that were funded based on the actual budget, but wouldn't have been after a 40 percent cut.

It's possible that some of the work funded by these "at risk" grants would have been done regardless. But the NIH is the largest supporter of biomedical research on the planet, so there aren't a ton of other options out there.

In any case, the researchers decided to look at the impact of the work funded by at-risk grants. Again, there are plenty of ways to judge impact: the patents arising from the work, the number of times papers funded by the grant were cited, and so on. However, the researchers decided to focus on the societal impact using one of the key outcomes of biomedical research: drugs.

Tracing that pathway is also surprisingly easy. The law that governs patenting of federally funded research requires that researchers report any patents arising from research back to the federal government. In addition, patents themselves allow the citation of scientific publications, which can also be traced back to grants.

So, the team started with the 557 drugs that have been approved between 2000 and 2023 and looked at the relevant patents, focusing on the ones issued prior to a drug's approval. Those patents were checked for citations of NIH-funded research or direct filings with the government.

From paper to patent

The simplest test is how many of them directly acknowledge support from an at-risk grant. That turned out to be 14, or 2.5 percent. While that number seems low, only 7 percent of the drugs in total directly acknowledged NIH support, so the at-risk grants represent a substantial proportion of that.

But it's also a somewhat unrealistic measure. Just about anything you do in biology now is based on decades of work done elsewhere, some of which may be absolutely essential to the final piece of research that led to the patent. That sort of intellectual contribution is likely to show up as a citation, rather than a direct acknowledgement. So, the researchers next focused on those citations.

It turns out that nearly 60 percent of the patents cite NIH-funded research. And here, the at-risk grants put in a very good showing, with just over half of the patents citing at least one at-risk grant. Note that many grants will have citations from both categories; to get a better sense, the researchers looked for patents where at least a quarter of the papers cited arose from NIH-funded research. For any grant, that number was a bit over 35 percent; for at-risk grants, it was about 12 percent.

Looking at specific examples, the researchers found that some of the approved drugs that relied on at-risk research were used for cancer treatments and genetic disorders. In other words, treatments that are likely to have a significant impact on public health. There are a couple of reasons to think that this is an underestimation of the impact, as well. To begin with, their source data on funding priorities stops at 2007, leaving a roughly 15-year gap where research funding can't be analyzed, but patents are still being filed.

In addition, drugs are just a small part of the potential impact of NIH research. "We excluded a wide range of important medical advances that may also build on NIH-funded research," the researchers acknowledge. "These include vaccines, gene and cell therapies, and other biologic drugs; diagnostic technologies and medical devices; as well as innovations in medical procedures, patient care practices, and surgical techniques." Beyond the obvious implications for public health, these sorts of patents can result in lots of economic activity, including the launching of entirely new businesses.

Beyond informing current debates about science funding, the research makes a larger point about scientific progress. We tend to focus on the major leaps forward and the high-profile scientists that drive them, as the upcoming Nobel Prizes highlight. But the reality is that most advances, especially in biology, are built on a broad intellectual foundation of lower-profile work that may require years for someone to find a way to apply it to anything patentable. Broad cuts like these may mean that the scientific superstars will still walk away with grants, while leaving a field devastated by having parts of this foundation knocked out from under it.

Science, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/science.aeb1564 (About DOIs).