- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 39 579

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

In 1982, a young Mac developer turned Jobs into a UI designer—and accidentally invented a new technique.

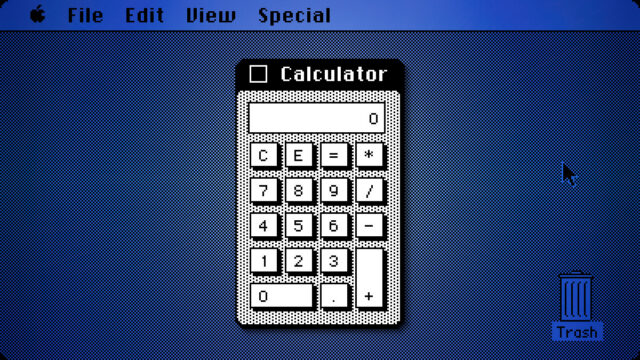

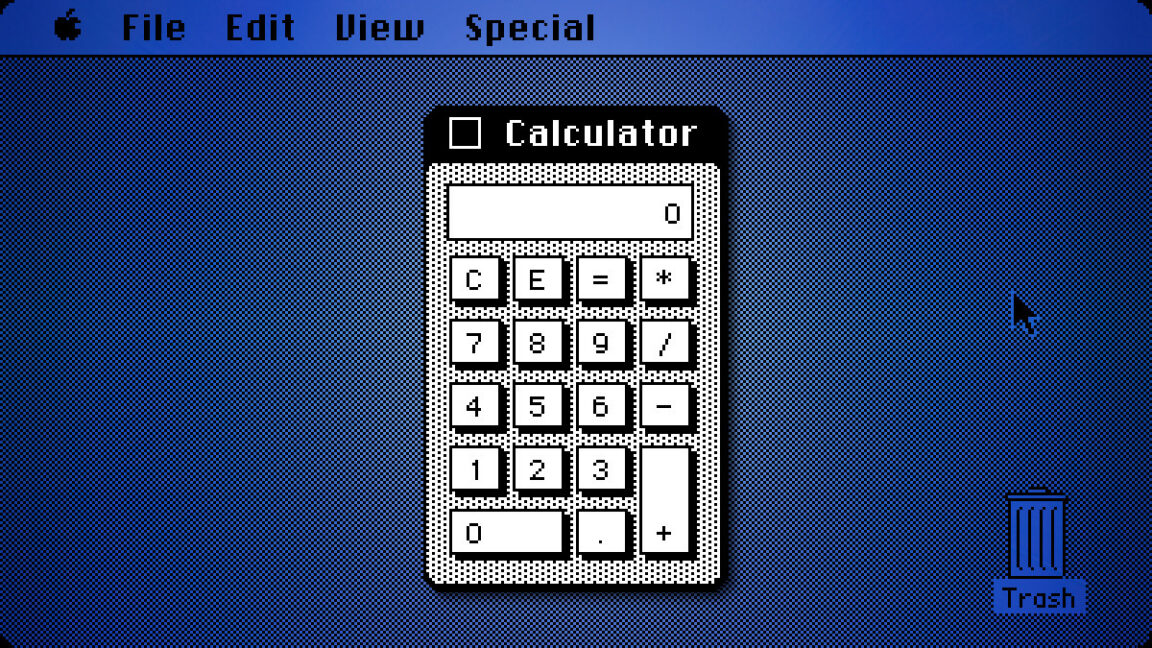

The Mac OS 1.0 calculator design. Credit: Apple / Benj Edwards

In February 1982, Apple employee #8 Chris Espinosa faced a problem that would feel familiar to anyone who has ever had a micromanaging boss: Steve Jobs wouldn’t stop critiquing his calculator design for the Mac. After days of revision cycles, the 21-year-old programmer found an elegant solution: He built what he called the “Steve Jobs Roll Your Own Calculator Construction Set” and let Jobs design it himself.

This delightful true story comes from Andy Hertzfeld’s Folklore.org, a legendary tech history site that chronicles the development of the original Macintosh, which was released in January 1984. I ran across the story again recently and thought it was worth sharing as a fun anecdote in an age where influential software designs often come by committee.

Design by menu

Chris Espinosa started working for Apple at age 14 in 1976 as the company’s youngest employee. By 1981, while studying at UC Berkeley, Jobs convinced Espinosa to drop out and work on the Mac team full time.

Believe it or not, Chris Espinosa still works at Apple as its longest-serving employee. But back in the day, as manager of documentation for the Macintosh, Espinosa decided to write a demo program using Bill Atkinson’s QuickDraw, the Mac’s graphics system, to better understand how it worked. He chose to create a calculator as one of the planned “desk ornaments,” which were small utility programs that would ship with the Mac. They later came to be called “desk accessories.”

Espinosa thought his initial calculator design looked good, but Jobs had other ideas when he saw it. Hertzfeld describes the scene: “Well, it’s a start,” Steve said, “but basically, it stinks. The background color is too dark, some lines are the wrong thickness, and the buttons are too big.”

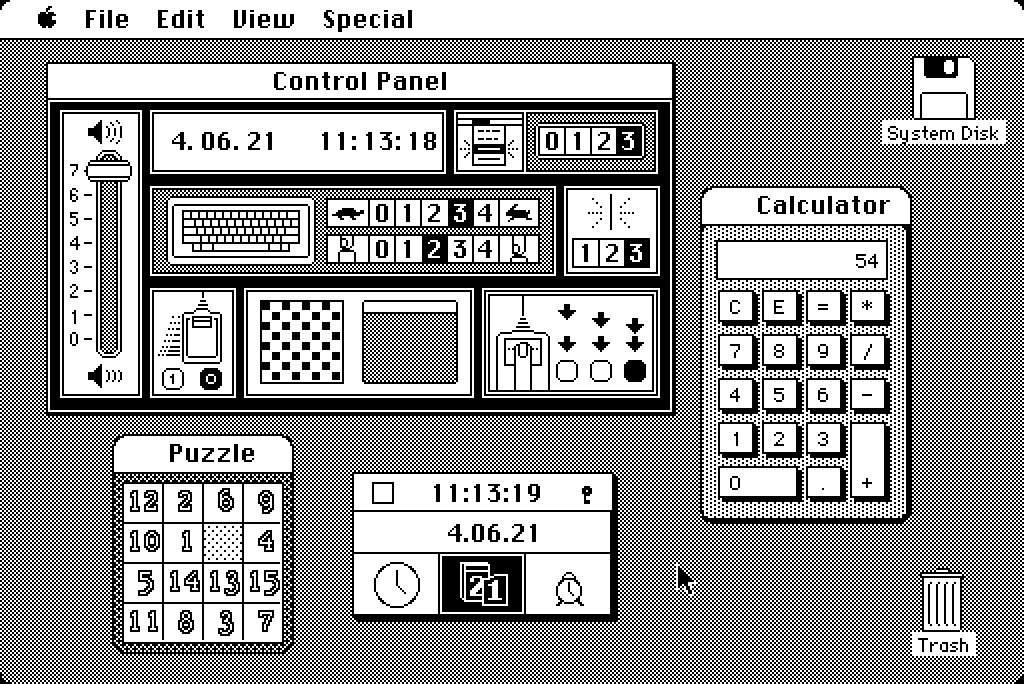

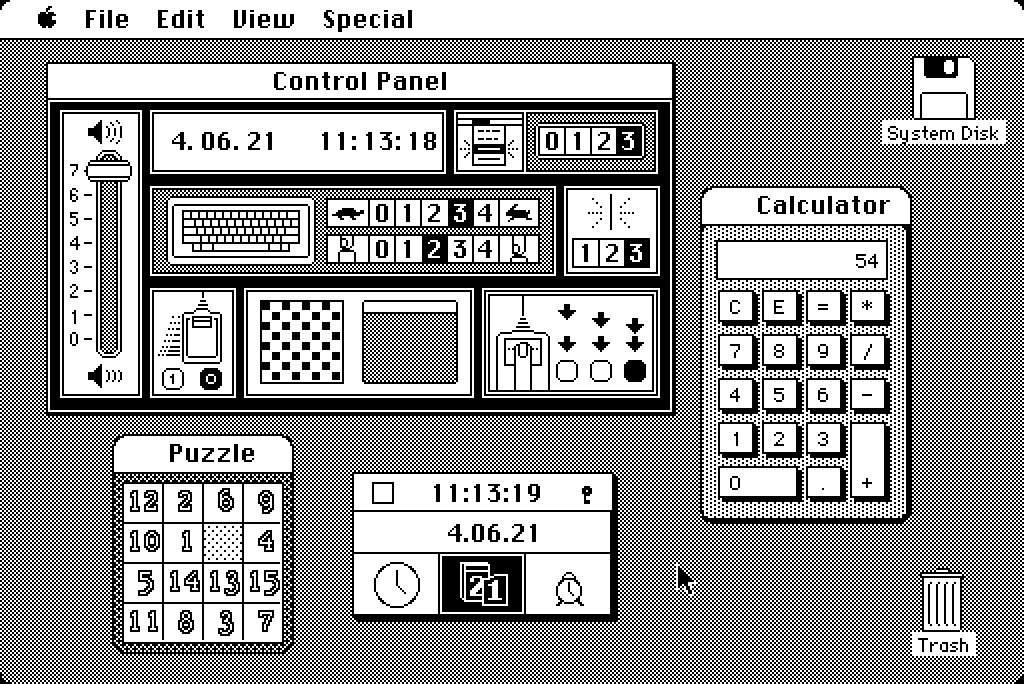

The Mac OS 1.0 calculator seen in situ with other desk accessories. Credit: Apple / Benj Edwards

For several days, Espinosa would incorporate Jobs’s suggestions from the previous day, only to have Jobs find new faults with each iteration. It might have felt like a classic case of “design by committee,” but in this case, the committee was just one very particular person who seemed impossible to satisfy.

Rather than continue the endless revision cycle, Espinosa took a different approach. According to Hertzfeld, Espinosa created a program that exposed every visual parameter of the calculator through pull-down menus: line thickness, button sizes, background patterns, and more. When Jobs sat down with it, he spent about ten minutes adjusting settings until he found a combination he liked.

The approach worked. When given direct control over the parameters rather than having to articulate his preferences verbally, Jobs quickly arrived at a design he was satisfied with. Hertzfeld notes that he implemented the calculator’s UI a few months later using Jobs’s parameter choices from that ten-minute session, while Donn Denman, another member of the Macintosh team, handled the mathematical functions.

That ten-minute session produced the calculator design that shipped with the Mac in 1984 and remained virtually unchanged through Mac OS 9, when Apple discontinued that OS in 2001. Apple replaced it in Mac OS X with a new design, ending the calculator’s 17-year run as the primary calculator interface for the Mac.

Why it worked

Espinosa’s Construction Set was an early example of what would later become common in software development: visual and parameterized design tools. In 1982, when most computers displayed monochrome text, the idea of letting someone fine-tune visual parameters through interactive controls without programming was fairly forward-thinking. Later, tools like HyperCard would formalize this kind of idea into a complete visual application framework.

The primitive calculator design tool also revealed something about Jobs’s management process. He knew what he wanted when he saw it, but he perhaps struggled to articulate it at times. By giving him direct manipulation ability, Espinosa did an end-run around that communication problem entirely. Later on, when he returned to Apple in the late 1990s, Jobs would famously insist on judging products by using them directly rather than through canned PowerPoint demos or lists of specifications.

The longevity of Jobs’s ten-minute design session suggests the approach worked. The calculator survived nearly two decades of Mac OS updates, outlasting many more elaborate interface elements. What started as a workaround became one of the Mac’s most simple but enduring designs.

By the way, if you want to try the original Mac OS calculator yourself, you can run various antique versions of the operating system in your browser thanks to the Infinite Mac website.

The Mac OS 1.0 calculator design. Credit: Apple / Benj Edwards

In February 1982, Apple employee #8 Chris Espinosa faced a problem that would feel familiar to anyone who has ever had a micromanaging boss: Steve Jobs wouldn’t stop critiquing his calculator design for the Mac. After days of revision cycles, the 21-year-old programmer found an elegant solution: He built what he called the “Steve Jobs Roll Your Own Calculator Construction Set” and let Jobs design it himself.

This delightful true story comes from Andy Hertzfeld’s Folklore.org, a legendary tech history site that chronicles the development of the original Macintosh, which was released in January 1984. I ran across the story again recently and thought it was worth sharing as a fun anecdote in an age where influential software designs often come by committee.

Design by menu

Chris Espinosa started working for Apple at age 14 in 1976 as the company’s youngest employee. By 1981, while studying at UC Berkeley, Jobs convinced Espinosa to drop out and work on the Mac team full time.

Believe it or not, Chris Espinosa still works at Apple as its longest-serving employee. But back in the day, as manager of documentation for the Macintosh, Espinosa decided to write a demo program using Bill Atkinson’s QuickDraw, the Mac’s graphics system, to better understand how it worked. He chose to create a calculator as one of the planned “desk ornaments,” which were small utility programs that would ship with the Mac. They later came to be called “desk accessories.”

Espinosa thought his initial calculator design looked good, but Jobs had other ideas when he saw it. Hertzfeld describes the scene: “Well, it’s a start,” Steve said, “but basically, it stinks. The background color is too dark, some lines are the wrong thickness, and the buttons are too big.”

The Mac OS 1.0 calculator seen in situ with other desk accessories. Credit: Apple / Benj Edwards

For several days, Espinosa would incorporate Jobs’s suggestions from the previous day, only to have Jobs find new faults with each iteration. It might have felt like a classic case of “design by committee,” but in this case, the committee was just one very particular person who seemed impossible to satisfy.

Rather than continue the endless revision cycle, Espinosa took a different approach. According to Hertzfeld, Espinosa created a program that exposed every visual parameter of the calculator through pull-down menus: line thickness, button sizes, background patterns, and more. When Jobs sat down with it, he spent about ten minutes adjusting settings until he found a combination he liked.

The approach worked. When given direct control over the parameters rather than having to articulate his preferences verbally, Jobs quickly arrived at a design he was satisfied with. Hertzfeld notes that he implemented the calculator’s UI a few months later using Jobs’s parameter choices from that ten-minute session, while Donn Denman, another member of the Macintosh team, handled the mathematical functions.

That ten-minute session produced the calculator design that shipped with the Mac in 1984 and remained virtually unchanged through Mac OS 9, when Apple discontinued that OS in 2001. Apple replaced it in Mac OS X with a new design, ending the calculator’s 17-year run as the primary calculator interface for the Mac.

Why it worked

Espinosa’s Construction Set was an early example of what would later become common in software development: visual and parameterized design tools. In 1982, when most computers displayed monochrome text, the idea of letting someone fine-tune visual parameters through interactive controls without programming was fairly forward-thinking. Later, tools like HyperCard would formalize this kind of idea into a complete visual application framework.

The primitive calculator design tool also revealed something about Jobs’s management process. He knew what he wanted when he saw it, but he perhaps struggled to articulate it at times. By giving him direct manipulation ability, Espinosa did an end-run around that communication problem entirely. Later on, when he returned to Apple in the late 1990s, Jobs would famously insist on judging products by using them directly rather than through canned PowerPoint demos or lists of specifications.

The longevity of Jobs’s ten-minute design session suggests the approach worked. The calculator survived nearly two decades of Mac OS updates, outlasting many more elaborate interface elements. What started as a workaround became one of the Mac’s most simple but enduring designs.

By the way, if you want to try the original Mac OS calculator yourself, you can run various antique versions of the operating system in your browser thanks to the Infinite Mac website.