- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 948

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

In trial, 82% saw weight rebound and cardiovascular health reverse after withdrawal.

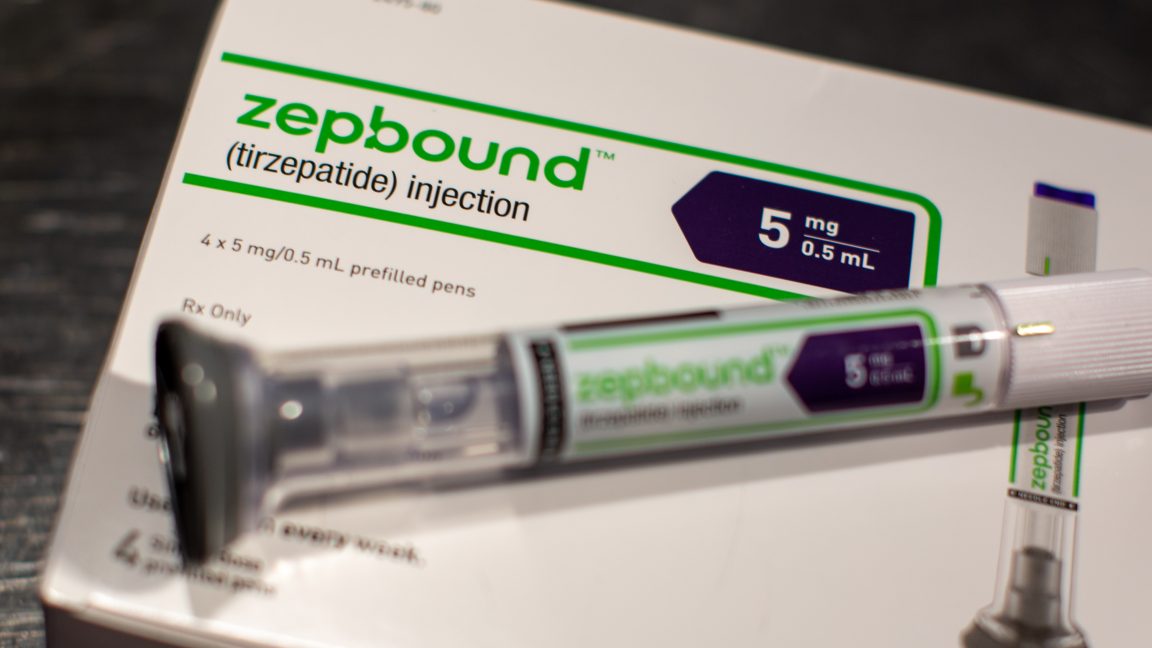

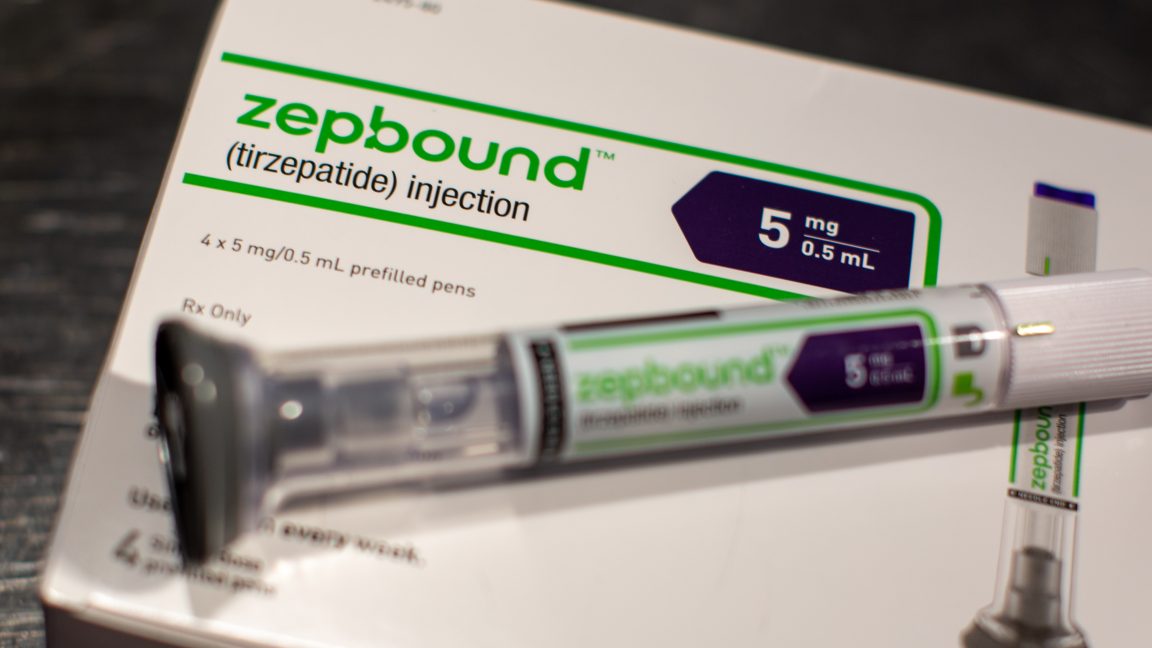

An Eli Lilly & Co. Zepbound injection pen arranged in Brooklyn, New York on March 28, 2024. Credit: Getty | helby Knowles

The popularity of GLP-1 weight-loss medications continues to soar—and their uptake is helping to push down obesity rates on a national scale—but a safe, evidence-based way off the drugs isn’t yet in clear view.

An analysis published this week in JAMA Internal Medicine found that most participants in a clinical trial who were assigned to stop taking tirzepatide (Zepbound from Eli Lilly) not only regained significant amounts of the weight they had lost on the drug, but they also saw their cardiovascular and metabolic improvements slip away. Their blood pressure went back up, as did their cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c (used to assess glucose control levels), and fasting insulin.

In an accompanying editorial, two medical experts at the University of Pittsburgh, Elizabeth Oczypok and Timothy Anderson, suggest that this new class of drugs should be rebranded from “weight loss” drugs to “weight management” drugs, which people may need to take indefinitely.

Some studies have found that about half of people who start taking a GLP-1 drug for weight loss stop taking it within a year—for various reasons—and many people think they can stop taking anti-obesity drugs once they’ve reached a desired weight, Oczypok and Anderson write. But that’s not in line with the data.

“It may be helpful to compare them to other chronic disease medications; patients do not stop their anti-hypertensive medications when their blood pressure is at goal,” they write.

In the trial, researchers—led by Eli Lilly scientists—followed 670 participants with obesity or overweight (but without diabetes) who were treated with tirzepatide for 36 weeks. Then the participants were split into either continuing with the drug for another 52 weeks (88 weeks total) or getting a placebo for that period of time. Both groups were told to continue a reduced-calorie diet and an exercise plan.

In all, 335 participants were randomized to switch to a placebo, and the researchers monitored changes in their weight and cardiovascular health metrics after the switch. Not everyone in the first phase of the trial lost significant amounts of weight on the drug. So, the researchers only closely tracked the 308 of the 335 who lost at least 10 percent of their body weight on the drug.

Of the 308 who benefited from tirzepatide, 254 (82 percent) regained at least 25 percent of the weight they had lost on the drug by week 88. Further, 177 (57 percent) regained at least 50 percent, and 74 (24 percent) regained at least 75 percent. Generally, the more weight people regained, the more their cardiovascular and metabolic health improvements reversed.

Data gaps and potential off-ramps

On the other hand, there were 54 participants of the 308 (17.5 percent) that didn’t regain a significant amount of weight (less than 25 percent.) This group saw some of their health metrics worsen on withdrawal of the drug, but not all— blood pressure increased a bit, but cholesterol didn’t go up significantly overall. About a dozen participants (4 percent of the 308) continued to lose weight after stopping the drug.

The researchers couldn’t figure out why these 54 participants fared so well; there were “no apparent differences” in demographic or clinical characteristics, they reported. It’s clear the topic requires further study.

But, overall, the study offers a gloomy outlook for patients hoping to avoid needing to take anti-obesity drugs for the foreseeable future.

Oczypok and Anderson highlight that the study involved an abrupt withdrawal from the drug. In contrast, many patients may be interested in slowly weaning off the drugs, stepping down dosage levels over time. So far, data on this strategy and the protocols to pull it off have little data behind them. It also might not be an option for patients who abruptly lose access or insurance coverage of the drugs. Other strategies for weaning off the drugs could involve ramping up physical activity or calorie restriction in anticipation of dropping the drugs, the experts note.

In addition to more data on potential GLP-1 off-ramps, the pair calls for more data on the effects of weight fluctuations from people going on and off the treatment. At least one study has found that the regained weight after intentional weight loss may end up being proportionally higher in fat mass, which could be harmful.

For now, Oczypok and Anderson say doctors should be cautious about talking with patients about these drugs and what the future could hold. “These results add to the body of evidence that clinicians and patients should approach starting [anti-obesity medications] as long-term therapies, just as they would medications for other chronic diseases.”

An Eli Lilly & Co. Zepbound injection pen arranged in Brooklyn, New York on March 28, 2024. Credit: Getty | helby Knowles

The popularity of GLP-1 weight-loss medications continues to soar—and their uptake is helping to push down obesity rates on a national scale—but a safe, evidence-based way off the drugs isn’t yet in clear view.

An analysis published this week in JAMA Internal Medicine found that most participants in a clinical trial who were assigned to stop taking tirzepatide (Zepbound from Eli Lilly) not only regained significant amounts of the weight they had lost on the drug, but they also saw their cardiovascular and metabolic improvements slip away. Their blood pressure went back up, as did their cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c (used to assess glucose control levels), and fasting insulin.

In an accompanying editorial, two medical experts at the University of Pittsburgh, Elizabeth Oczypok and Timothy Anderson, suggest that this new class of drugs should be rebranded from “weight loss” drugs to “weight management” drugs, which people may need to take indefinitely.

Some studies have found that about half of people who start taking a GLP-1 drug for weight loss stop taking it within a year—for various reasons—and many people think they can stop taking anti-obesity drugs once they’ve reached a desired weight, Oczypok and Anderson write. But that’s not in line with the data.

“It may be helpful to compare them to other chronic disease medications; patients do not stop their anti-hypertensive medications when their blood pressure is at goal,” they write.

In the trial, researchers—led by Eli Lilly scientists—followed 670 participants with obesity or overweight (but without diabetes) who were treated with tirzepatide for 36 weeks. Then the participants were split into either continuing with the drug for another 52 weeks (88 weeks total) or getting a placebo for that period of time. Both groups were told to continue a reduced-calorie diet and an exercise plan.

In all, 335 participants were randomized to switch to a placebo, and the researchers monitored changes in their weight and cardiovascular health metrics after the switch. Not everyone in the first phase of the trial lost significant amounts of weight on the drug. So, the researchers only closely tracked the 308 of the 335 who lost at least 10 percent of their body weight on the drug.

Of the 308 who benefited from tirzepatide, 254 (82 percent) regained at least 25 percent of the weight they had lost on the drug by week 88. Further, 177 (57 percent) regained at least 50 percent, and 74 (24 percent) regained at least 75 percent. Generally, the more weight people regained, the more their cardiovascular and metabolic health improvements reversed.

Data gaps and potential off-ramps

On the other hand, there were 54 participants of the 308 (17.5 percent) that didn’t regain a significant amount of weight (less than 25 percent.) This group saw some of their health metrics worsen on withdrawal of the drug, but not all— blood pressure increased a bit, but cholesterol didn’t go up significantly overall. About a dozen participants (4 percent of the 308) continued to lose weight after stopping the drug.

The researchers couldn’t figure out why these 54 participants fared so well; there were “no apparent differences” in demographic or clinical characteristics, they reported. It’s clear the topic requires further study.

But, overall, the study offers a gloomy outlook for patients hoping to avoid needing to take anti-obesity drugs for the foreseeable future.

Oczypok and Anderson highlight that the study involved an abrupt withdrawal from the drug. In contrast, many patients may be interested in slowly weaning off the drugs, stepping down dosage levels over time. So far, data on this strategy and the protocols to pull it off have little data behind them. It also might not be an option for patients who abruptly lose access or insurance coverage of the drugs. Other strategies for weaning off the drugs could involve ramping up physical activity or calorie restriction in anticipation of dropping the drugs, the experts note.

In addition to more data on potential GLP-1 off-ramps, the pair calls for more data on the effects of weight fluctuations from people going on and off the treatment. At least one study has found that the regained weight after intentional weight loss may end up being proportionally higher in fat mass, which could be harmful.

For now, Oczypok and Anderson say doctors should be cautious about talking with patients about these drugs and what the future could hold. “These results add to the body of evidence that clinicians and patients should approach starting [anti-obesity medications] as long-term therapies, just as they would medications for other chronic diseases.”