- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 838

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

Hypervirulent germ nearly destroys man, invading brain and blowing out an eye.

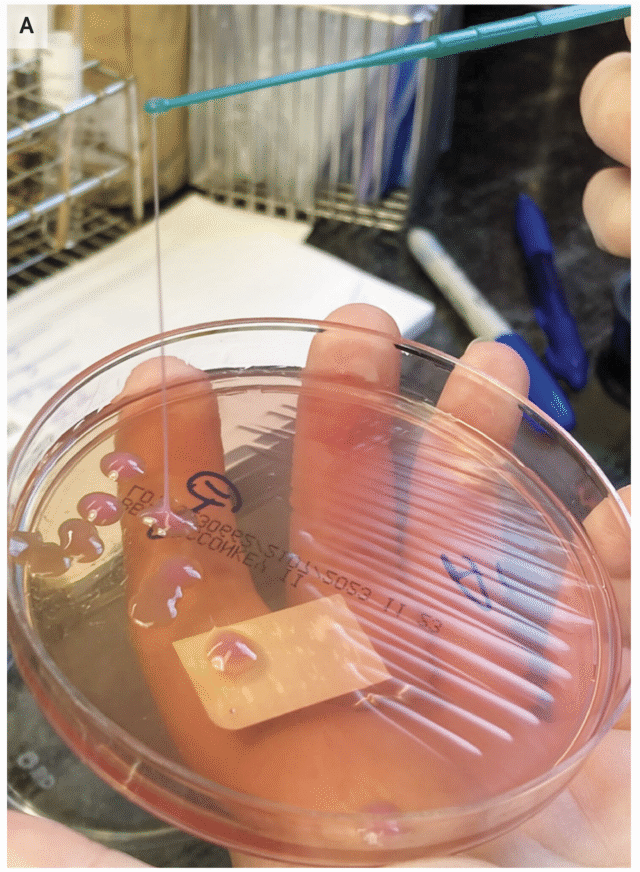

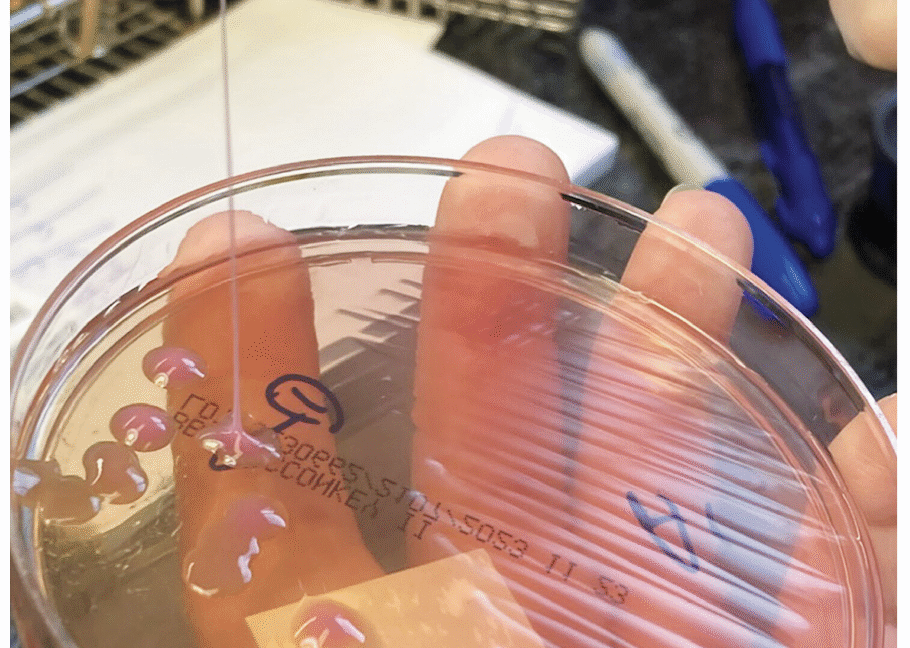

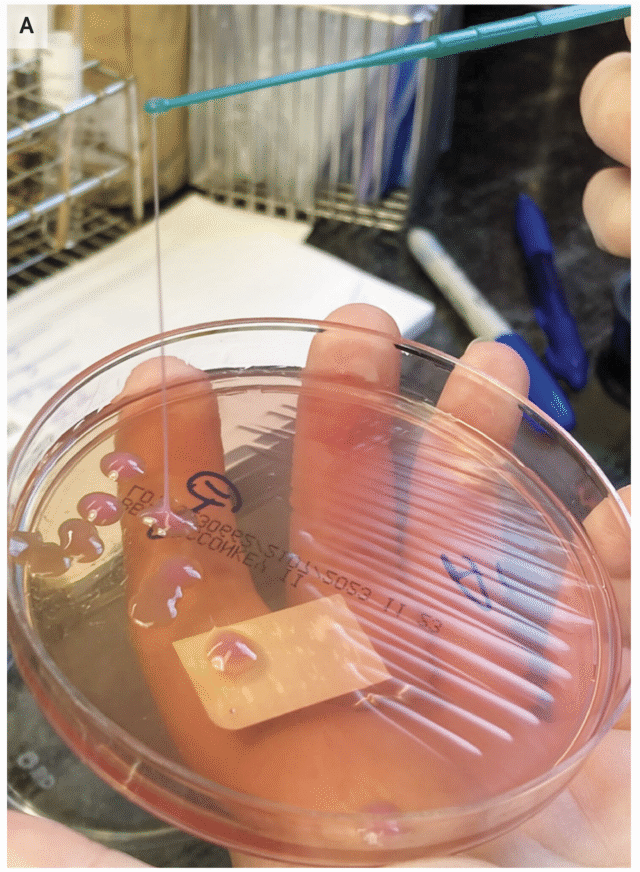

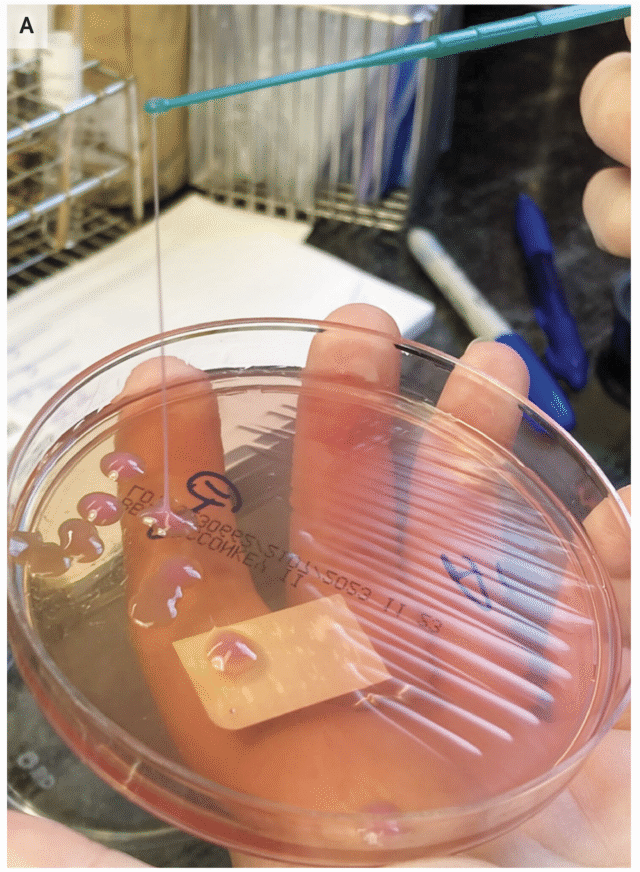

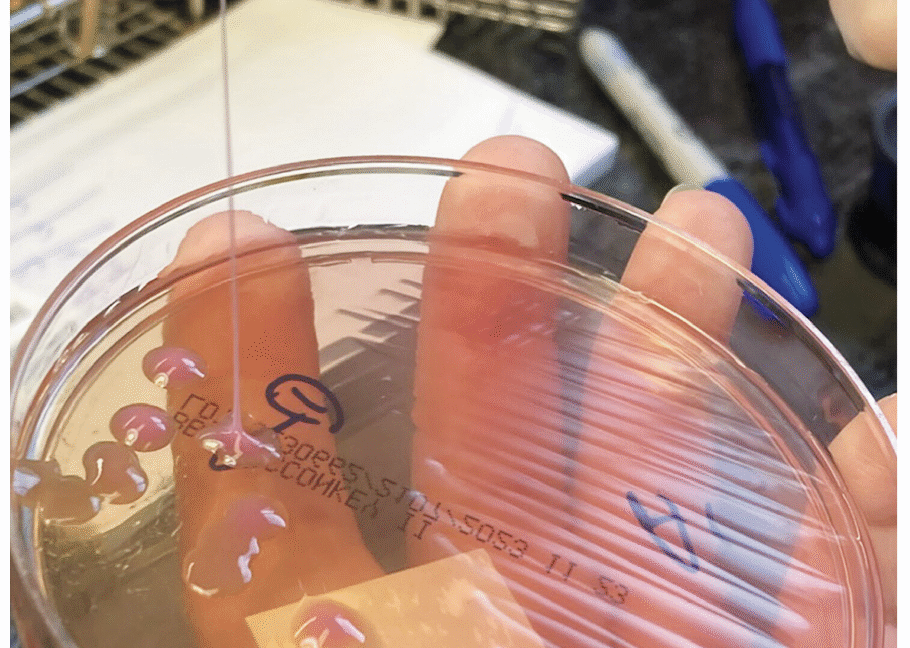

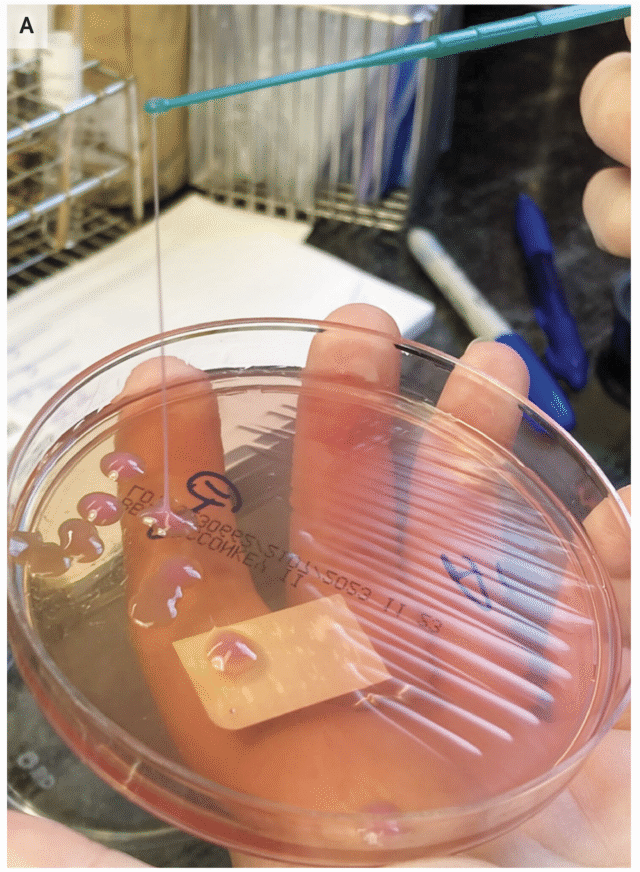

A string test performed on the rare growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae from the sputum culture shows a positive result, with the formation of a viscous string with a height of greater than 5 mm. Credit: NEJM 2026

A generally healthy 63-year-old man in the New England area went to the hospital with a fever, cough, and vision problems in his right eye. What his doctors eventually figured out was that a dreaded hypervirulent bacteria—which is rising globally—was ravaging several of his organs, including his brain.

According to the man, the problems had started three weeks before his hospital visit, when he said he ate some bad meat and started having vomiting and diarrhea. Those symptoms faded after about two weeks, but then new problems began; he started coughing and having chills and a fever. His cough only worsened from there.

At the hospital, doctors took X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans of his chest and abdomen. The images revealed over 15 nodules and masses in his lungs. But, that’s not all they found. The imaging also revealed a mass in his liver that was 8.6 cm in diameter (about 3.4 inches). Lab work pointed toward an infection. So, doctors admitted him to the hospital and provided oxygen to help with his breathing, as well as antibiotics. But his chills and cough continued.

On his third day, he woke up with vision loss in his right eye, which was so swollen that he couldn’t open it. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed another surprise: there were multiple lesions in his brain. (His brain lesions and eye at this point can be seen here. A later-stage image of his eye is further down in the story.) At that point, he was transferred to Massachusetts General Hospital. In a case report in this week’s issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, doctors went through how they solved the case and treated the man.

The key to the correct diagnosis was his eye, which kept getting worse. He seemed to have an infection inside his eyeball, affecting the jelly or aqueous parts of the inside (endophthalmitis). The most common cause of this is an eye injury or previous surgery that allows an infection-sparking germ to get in—but he had no such injury or surgery. Also, the condition of his eye was worse than that. He appeared to have panophthalmitis, which is a rare, extremely severe and rapidly progressing condition in which every part of the eye becomes infected.

Savage microbe

Whatever was laying waste to his eye seemed to have come from inside his own body, carried in his bloodstream—possibly the same thing that could explain the liver mass, lung nodules, and brain lesions. There was one explanation that fit the condition perfectly: hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae or hvKP.

Classical K. pneumoniae is a germ that dwells in people’s intestinal tracts and is one that’s familiar to doctors. It’s known for lurking in health care settings and infecting vulnerable patients, often causing pneumonia or urinary tract infections. But, hvKP is very different. In comparison, it’s a beefed-up bacteria with a rage complex. It was first identified in the 1980s in Taiwan—not for stalking weak patients in the hospital, but devastating healthy people in normal community settings.

An infection with hvKP—even in otherwise healthy people—is marked by metastatic infection. That is, the bacteria spread throughout the body, usually starting with the liver, where it creates a pus-filled abscess. Then it goes on a trip through the bloodstream, invading the lungs, brain, soft tissue, skin, and the eye (endogenous endophthalmitis). Putting it all together, the man had a completely typical clinical case of an hvKP infection.

Still, definitely identifying hvKP is tricky. Mucus from the man’s respiratory tract grew a species of Klebsiella, but there is not yet a solid diagnostic test to differentiate hvKP from the classical variety. Just since 2024, researchers have worked out a strategy of using the presence of five different virulence genes found on plasmids (relatively small, circular pieces of DNA, separate from chromosomal DNA, that can replicate on their own and be shared among bacteria.) But the method isn’t perfect—some classical K. pneumoniae can also carry the five genes.

A string test performed on the rare growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae from the sputum culture shows a positive result, with the formation of a viscous string with a height of greater than 5 mm. Credit: NEJM 2026

Another, much simpler method is the string test, in which clinicians basically test the goopy-ness of the bacteria—hvKP is known for being sticky. For this test, a clinician grows the bacteria into a colony on a petri dish then touches an inoculation loop to the colony and pulls up. If the string of attached goo stretches more than 5 mm off the petri dish, it’s considered positive for hvKP. But, this is (obviously) not a precise test.

Recovery

In the man’s case, the bacteria from his respiratory tract was positive in the string test. Doctors treated him with antibiotics that testing found could kill off the hvKP strain he had.

Still, it was too late for the man’s eye. By his eighth day in the hospital, the swelling had gotten extremely severe (you can see an image here, but be warned that it is very disturbing). His eye was now bulging out of his head and imaging suggested another abscess had formed on the side of the eyeball. He had severe stretching of his optic nerve. Overall, there was no chance of him recovering sight in that eye. Given the worsening situation—which was despite the effective antibiotics—doctors removed his eye.

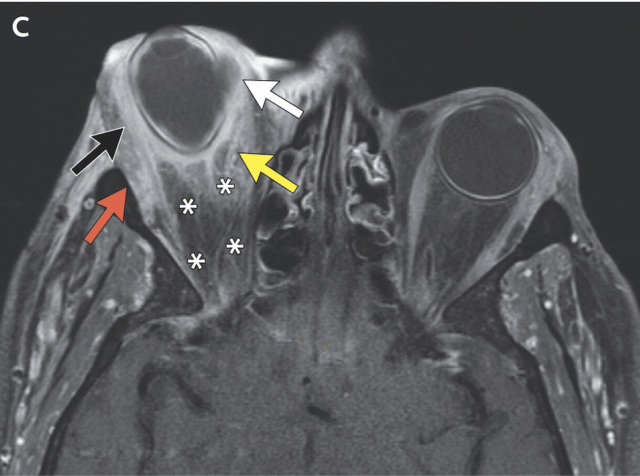

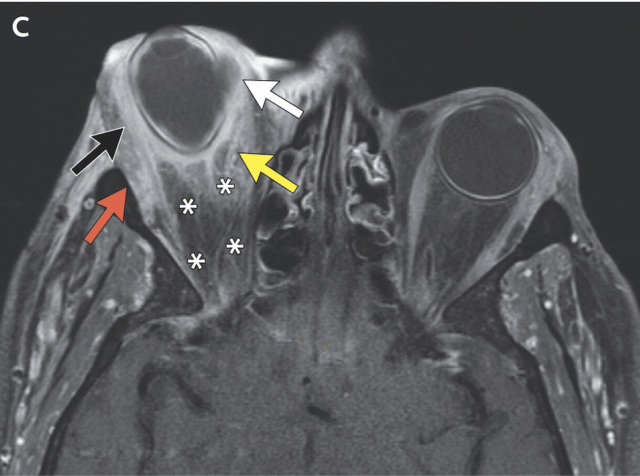

Circumferential right scleral enhancement (black arrow) is present, and postseptal soft‑tissue inflammatory changes (yellow arrow) that also involved the right extraocular muscles (red arrow) are seen. Credit: NEJM 2026

In these cases, it’s sometimes recommended to drain the liver abscess and surgically remove the brain lesions, too. But doctors ruled out both of those options. The liver abscess was too varied for simple drainage and the brain lesions were too small and numerous to make surgery safe. Instead, he went through an intense antibiotic regimen that, in the end, lasted nine months. Fortunately, by then, imaging confirmed that his liver abscess had resolved, his lung nodules nearly vanished, and his brain lesions significantly shrank or disappeared.

His doctors also noted that he was lucky in having an hvKP strain that did not carry significant resistance to antibiotics. In recent years, health officials have flagged not just a global increase of hvKP cases overall, but also an increase in hvKP cases that are resistant to critical antibiotics, specifically carbapenemases or extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. These cases can have fatality rates above 50 percent.

Eric

We've all been avoiding the media page in our CMS while Beth's been working on this story...

...for good reason

January 16, 2026 at 9:36 pm

A string test performed on the rare growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae from the sputum culture shows a positive result, with the formation of a viscous string with a height of greater than 5 mm. Credit: NEJM 2026

A generally healthy 63-year-old man in the New England area went to the hospital with a fever, cough, and vision problems in his right eye. What his doctors eventually figured out was that a dreaded hypervirulent bacteria—which is rising globally—was ravaging several of his organs, including his brain.

According to the man, the problems had started three weeks before his hospital visit, when he said he ate some bad meat and started having vomiting and diarrhea. Those symptoms faded after about two weeks, but then new problems began; he started coughing and having chills and a fever. His cough only worsened from there.

At the hospital, doctors took X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans of his chest and abdomen. The images revealed over 15 nodules and masses in his lungs. But, that’s not all they found. The imaging also revealed a mass in his liver that was 8.6 cm in diameter (about 3.4 inches). Lab work pointed toward an infection. So, doctors admitted him to the hospital and provided oxygen to help with his breathing, as well as antibiotics. But his chills and cough continued.

On his third day, he woke up with vision loss in his right eye, which was so swollen that he couldn’t open it. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed another surprise: there were multiple lesions in his brain. (His brain lesions and eye at this point can be seen here. A later-stage image of his eye is further down in the story.) At that point, he was transferred to Massachusetts General Hospital. In a case report in this week’s issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, doctors went through how they solved the case and treated the man.

The key to the correct diagnosis was his eye, which kept getting worse. He seemed to have an infection inside his eyeball, affecting the jelly or aqueous parts of the inside (endophthalmitis). The most common cause of this is an eye injury or previous surgery that allows an infection-sparking germ to get in—but he had no such injury or surgery. Also, the condition of his eye was worse than that. He appeared to have panophthalmitis, which is a rare, extremely severe and rapidly progressing condition in which every part of the eye becomes infected.

Savage microbe

Whatever was laying waste to his eye seemed to have come from inside his own body, carried in his bloodstream—possibly the same thing that could explain the liver mass, lung nodules, and brain lesions. There was one explanation that fit the condition perfectly: hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae or hvKP.

Classical K. pneumoniae is a germ that dwells in people’s intestinal tracts and is one that’s familiar to doctors. It’s known for lurking in health care settings and infecting vulnerable patients, often causing pneumonia or urinary tract infections. But, hvKP is very different. In comparison, it’s a beefed-up bacteria with a rage complex. It was first identified in the 1980s in Taiwan—not for stalking weak patients in the hospital, but devastating healthy people in normal community settings.

An infection with hvKP—even in otherwise healthy people—is marked by metastatic infection. That is, the bacteria spread throughout the body, usually starting with the liver, where it creates a pus-filled abscess. Then it goes on a trip through the bloodstream, invading the lungs, brain, soft tissue, skin, and the eye (endogenous endophthalmitis). Putting it all together, the man had a completely typical clinical case of an hvKP infection.

Still, definitely identifying hvKP is tricky. Mucus from the man’s respiratory tract grew a species of Klebsiella, but there is not yet a solid diagnostic test to differentiate hvKP from the classical variety. Just since 2024, researchers have worked out a strategy of using the presence of five different virulence genes found on plasmids (relatively small, circular pieces of DNA, separate from chromosomal DNA, that can replicate on their own and be shared among bacteria.) But the method isn’t perfect—some classical K. pneumoniae can also carry the five genes.

A string test performed on the rare growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae from the sputum culture shows a positive result, with the formation of a viscous string with a height of greater than 5 mm. Credit: NEJM 2026

Another, much simpler method is the string test, in which clinicians basically test the goopy-ness of the bacteria—hvKP is known for being sticky. For this test, a clinician grows the bacteria into a colony on a petri dish then touches an inoculation loop to the colony and pulls up. If the string of attached goo stretches more than 5 mm off the petri dish, it’s considered positive for hvKP. But, this is (obviously) not a precise test.

Recovery

In the man’s case, the bacteria from his respiratory tract was positive in the string test. Doctors treated him with antibiotics that testing found could kill off the hvKP strain he had.

Still, it was too late for the man’s eye. By his eighth day in the hospital, the swelling had gotten extremely severe (you can see an image here, but be warned that it is very disturbing). His eye was now bulging out of his head and imaging suggested another abscess had formed on the side of the eyeball. He had severe stretching of his optic nerve. Overall, there was no chance of him recovering sight in that eye. Given the worsening situation—which was despite the effective antibiotics—doctors removed his eye.

Circumferential right scleral enhancement (black arrow) is present, and postseptal soft‑tissue inflammatory changes (yellow arrow) that also involved the right extraocular muscles (red arrow) are seen. Credit: NEJM 2026

In these cases, it’s sometimes recommended to drain the liver abscess and surgically remove the brain lesions, too. But doctors ruled out both of those options. The liver abscess was too varied for simple drainage and the brain lesions were too small and numerous to make surgery safe. Instead, he went through an intense antibiotic regimen that, in the end, lasted nine months. Fortunately, by then, imaging confirmed that his liver abscess had resolved, his lung nodules nearly vanished, and his brain lesions significantly shrank or disappeared.

His doctors also noted that he was lucky in having an hvKP strain that did not carry significant resistance to antibiotics. In recent years, health officials have flagged not just a global increase of hvKP cases overall, but also an increase in hvKP cases that are resistant to critical antibiotics, specifically carbapenemases or extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. These cases can have fatality rates above 50 percent.

Eric

We've all been avoiding the media page in our CMS while Beth's been working on this story...

...for good reason

January 16, 2026 at 9:36 pm