- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 39 683

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

Study identified several trace chemical signatures of opium in ancient Egyptian alabaster vase.

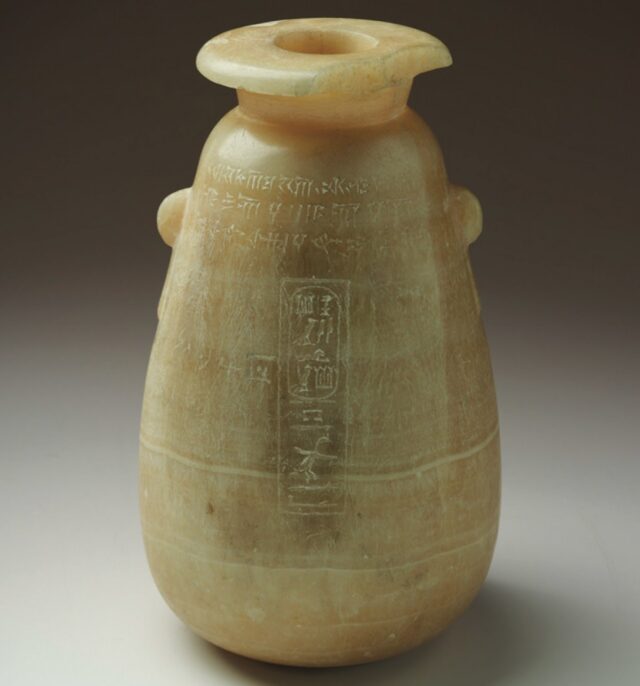

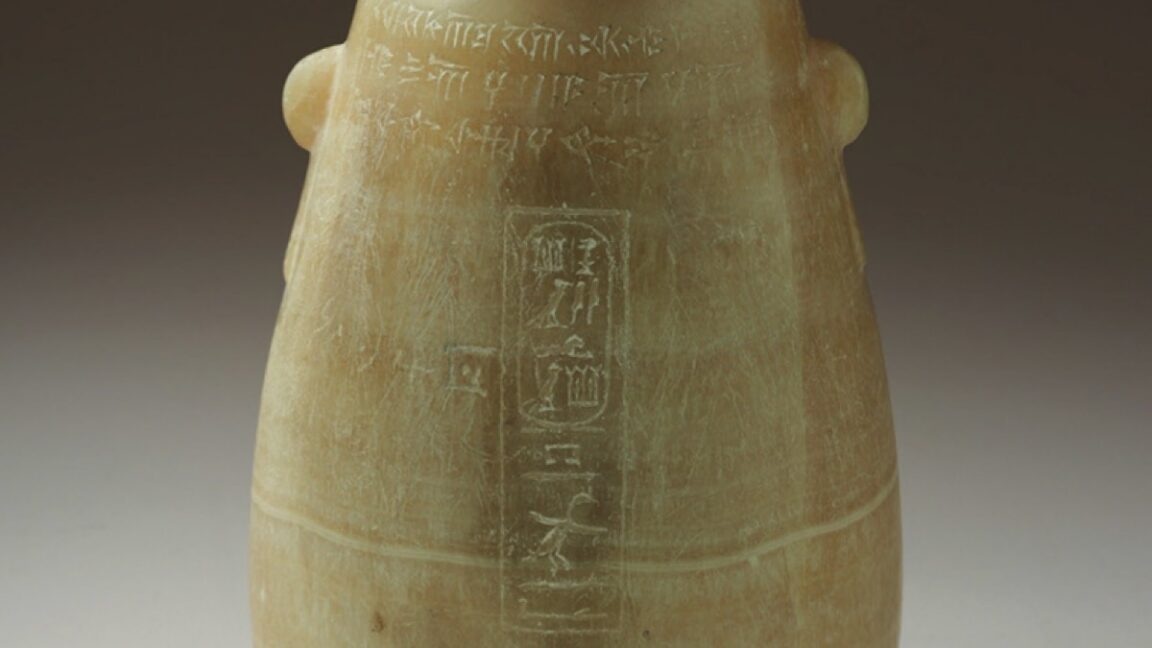

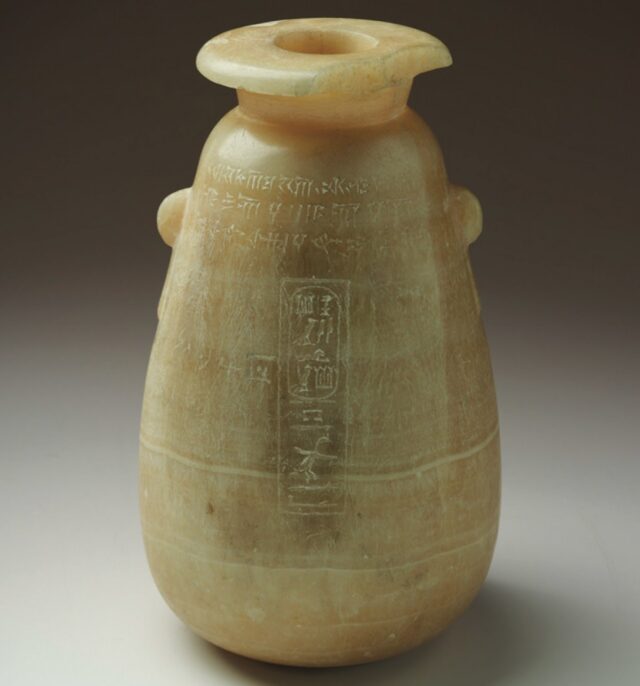

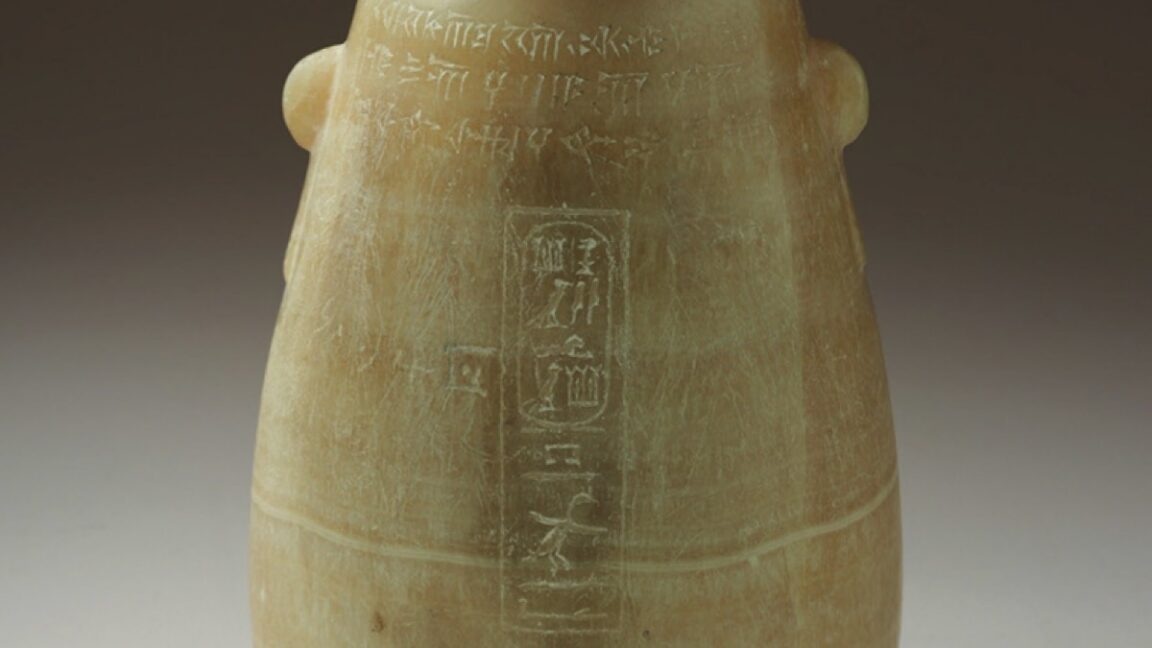

Yale Babylonian Collection (YBC) Egyptian alabastron Credit: Courtesy of the Yale Babylonian Collection;

Scientists have found traces of ancient opiates in the residue lining an Egyptian alabaster vase, indicating that opiate use was woven into the fabric of the culture. And the Egyptians didn’t just indulge occasionally: according to a paper published in the Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology, opiate use may have been a fixture of daily life.

In recent years, archaeologists have been applying the tools of pharmacology to excavated artifacts in collections around the world. As previously reported, there is ample evidence that humans in many cultures throughout history used various hallucinogenic substances in religious ceremonies or shamanic rituals. That includes not just ancient Egypt but also ancient Greek, Vedic, Maya, Inca, and Aztec cultures. The Urarina people who live in the Peruvian Amazon Basin still use a psychoactive brew called ayahuasca in their rituals, and Westerners seeking their own brand of enlightenment have also been known to participate.

For instance, in 2023, David Tanasi, of the University of South Florida, posted a preprint on his preliminary analysis of a ceremonial mug decorated with the head of Bes, a popular deity believed to confer protection on households, especially mothers and children. After collecting sample residues from the vessel, Tanasi applied various techniques—including proteomic and genetic analyses and synchrotron radiation-based Fourier-transform infrared microspectroscopy—to characterize the residues.

Tanasi found traces of Syrian rue, whose seeds are known to have hallucinogenic properties that can induce dream-like visions, per the authors, thanks to its production of the alkaloids harmine and harmaline. There were also traces of blue water lily, which contains a psychoactive alkaloid that acts as a sedative, as well as a fermented alcoholic concoction containing yeasts, wheat, sesame seeds, fruit (possibly grapes), honey, and, um, “human fluids”: possibly breast milk, oral or vaginal mucus, and blood. A follow-up 2024 study confirmed those results and also found traces of pine nuts or Mediterranean pine oil; licorice; tartaric acid salts that were likely part of the aforementioned alcoholic concoction; and traces of spider flowers known to have medicinal properties.

Vessels of alabaster

Now we can add opiates to the list of pharmacological substances used by the ancient Egyptians. The authors of this latest paper focused on one alabaster vase in particular, housed in the Yale Peabody Museum’s Babylonian Collection. The vase is intact—a rare find—and is inscribed in four ancient languages and mentions Xerxes I, who reigned over the Achaemenid Empire from 486 to 465 BCE. The authors were particularly intrigued by the presence of a dark-brown residue inside the vase.

Papaver somnifera entry in a facsimile of the ca. 515 CE Anicia Juliana Codex of De materia medica by Dioscorides. C. Zollo/courtesy of Medical Historical Library, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

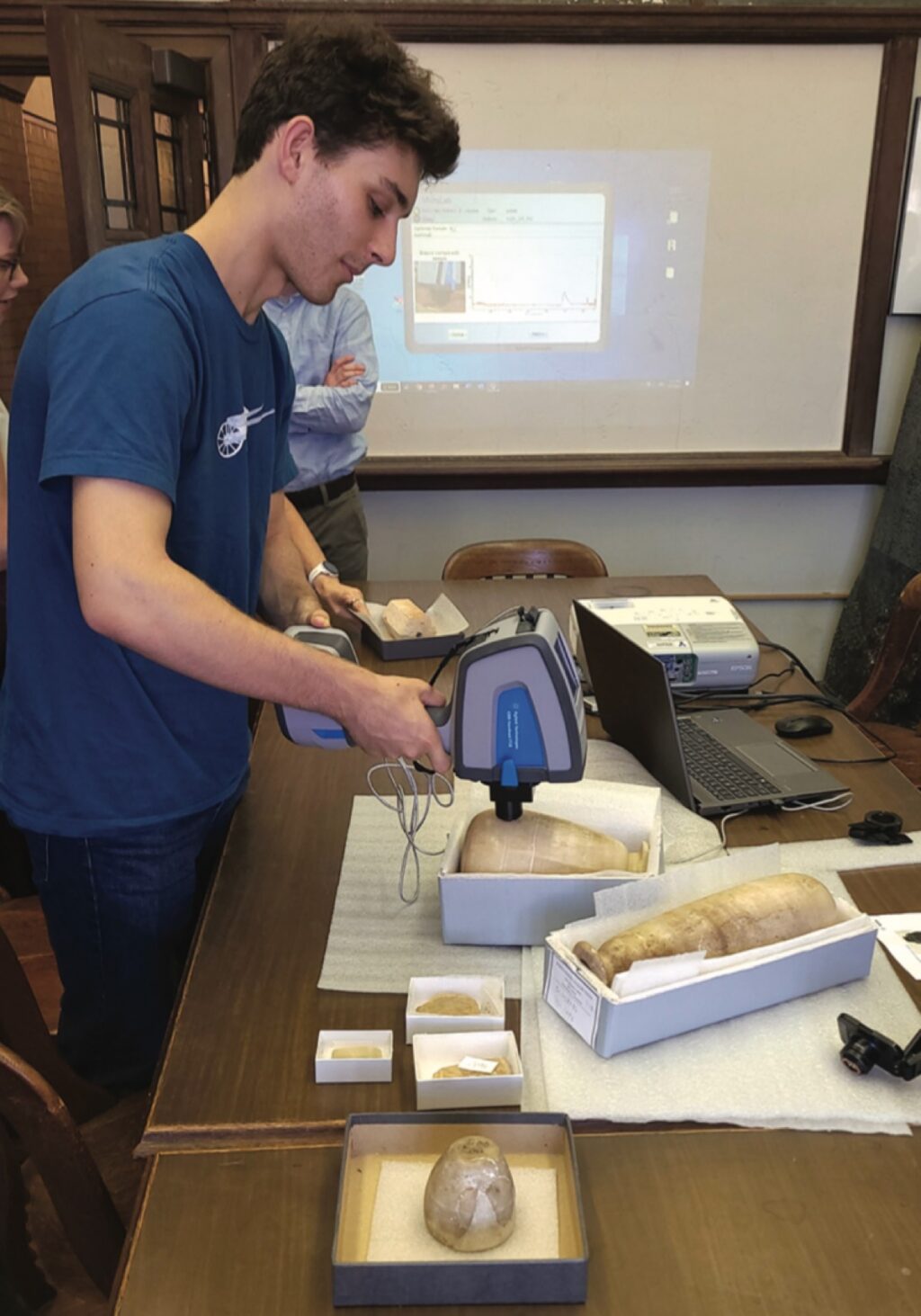

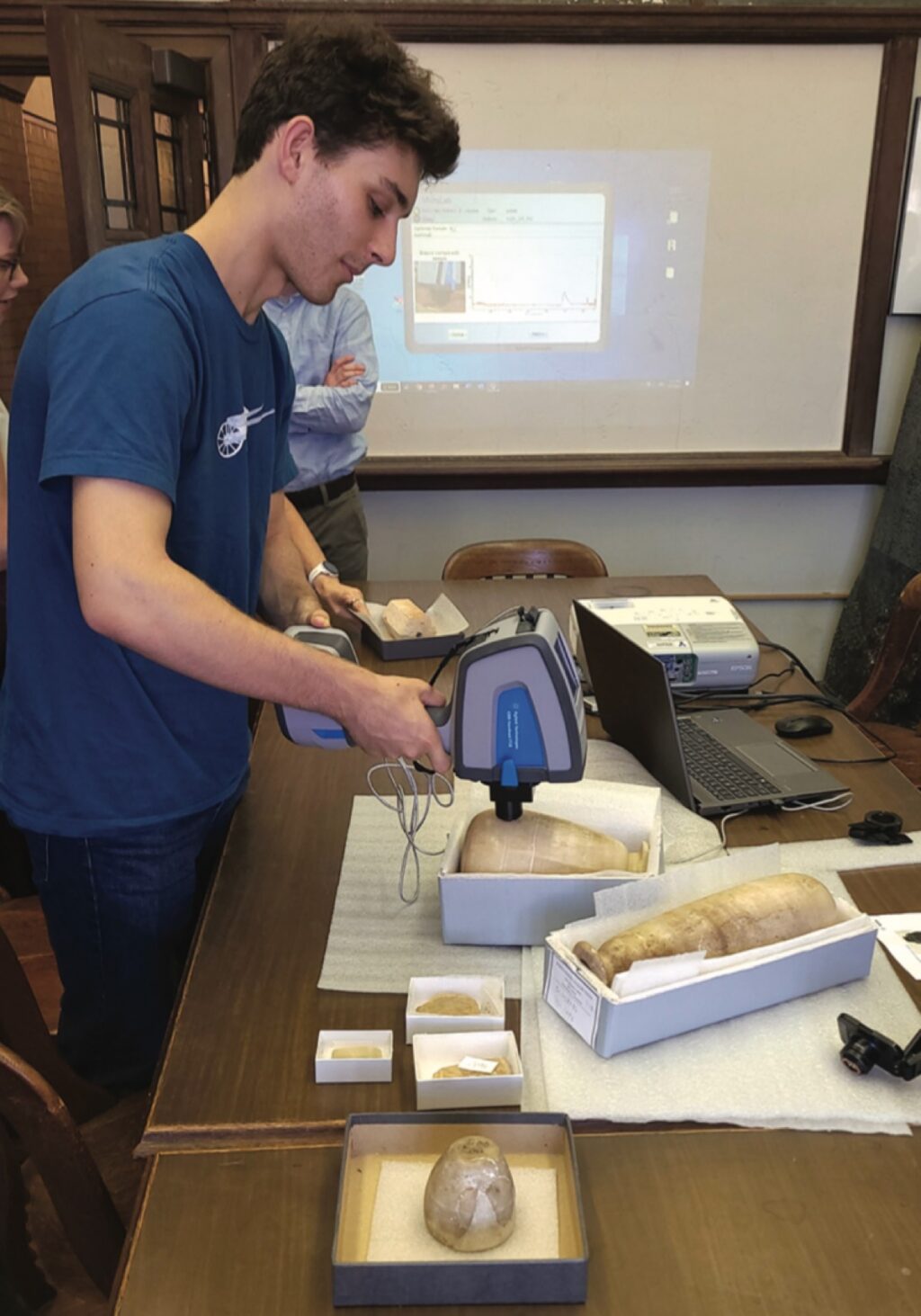

pXRF analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

FTIR analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

pXRF analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

FTIR analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

Past scholars had speculated the vases most likely held cosmetics or perfumes, or perhaps hidden messages between the king and his officials. Yet there are also several known pharmacopeia recipes contained in such works as the Anicia Juliana Codex of De materia medica by Dioscorides. The current authors analyzed residue samples with nondestructive techniques, namely portable X-ray fluorescence XRF (pXRF) and passive Fourier Transform Infrared (pFTIR) spectroscopy.

The result: distinct traces of several biomarkers for opium, such as noscapine, hydrocotarnine, morphine, thebaine, and papaverine. That’s consistent with an earlier identification of opiate residues found in several Egyptian alabaster vessels and Cypriot juglets excavated from a merchant’s tomb south of Cairo, dating back to the New Kingdom (16th to 11th century BCE).

The authors think these twin findings warrant a reassessment of prior assumptions about Egyptian alabaster vessels, many of which they believe could also have traces of ancient opiates. A good starting point, they suggest, is a set of vessels excavated from Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 by archaeologist Howard Carter. Many of those vessels have the same sticky dark brown organic residues. There was an early attempt to chemically analyze those residues in 1933 by Albert Lucas, who simply didn’t have the necessary technology to identify the compounds, although he was able to determine that the residues were not unguents or perfumes. Nobody has attempted to analyze the residues since.

Additional evidence of the value of the residues lies in the fact that looters didn’t engage in the usual “smash and grab” practices employed to collect precious metals when it came to the alabaster vessels. Instead, looters transferred the organic stuff into portable bags; there are still finger marks inside many of the vessels, as well as remnants of the leather bags used to collect the organics.

“It remains imminently possible, if not probable, that at least some of the vast remaining bulk of calcite vessels… in fact contained opiates as part of a long-lived Egyptian tradition we are only beginning to understand,” the authors concluded. Looters missed a few of the vessels, which still contain their original organic contents, making them ideal candidates for future analysis.

“We now have found opiate chemical signatures that Egyptian alabaster vessels attached to elite societies in Mesopotamia and embedded in more ordinary cultural circumstances within ancient Egypt,” said co-author Andrew Koh of the Yale Peabody Museum. “It’s possible these vessels were easily recognizable cultural markers for opium use in ancient times, just as hookahs today are attached to shisha tobacco consumption. Analyzing the contents of the jars from King Tut’s tomb would further clarify the role of opium in these ancient societies.”

DOI: Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology, 2025. 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.13.3.0317 (About DOIs).

Yale Babylonian Collection (YBC) Egyptian alabastron Credit: Courtesy of the Yale Babylonian Collection;

Scientists have found traces of ancient opiates in the residue lining an Egyptian alabaster vase, indicating that opiate use was woven into the fabric of the culture. And the Egyptians didn’t just indulge occasionally: according to a paper published in the Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology, opiate use may have been a fixture of daily life.

In recent years, archaeologists have been applying the tools of pharmacology to excavated artifacts in collections around the world. As previously reported, there is ample evidence that humans in many cultures throughout history used various hallucinogenic substances in religious ceremonies or shamanic rituals. That includes not just ancient Egypt but also ancient Greek, Vedic, Maya, Inca, and Aztec cultures. The Urarina people who live in the Peruvian Amazon Basin still use a psychoactive brew called ayahuasca in their rituals, and Westerners seeking their own brand of enlightenment have also been known to participate.

For instance, in 2023, David Tanasi, of the University of South Florida, posted a preprint on his preliminary analysis of a ceremonial mug decorated with the head of Bes, a popular deity believed to confer protection on households, especially mothers and children. After collecting sample residues from the vessel, Tanasi applied various techniques—including proteomic and genetic analyses and synchrotron radiation-based Fourier-transform infrared microspectroscopy—to characterize the residues.

Tanasi found traces of Syrian rue, whose seeds are known to have hallucinogenic properties that can induce dream-like visions, per the authors, thanks to its production of the alkaloids harmine and harmaline. There were also traces of blue water lily, which contains a psychoactive alkaloid that acts as a sedative, as well as a fermented alcoholic concoction containing yeasts, wheat, sesame seeds, fruit (possibly grapes), honey, and, um, “human fluids”: possibly breast milk, oral or vaginal mucus, and blood. A follow-up 2024 study confirmed those results and also found traces of pine nuts or Mediterranean pine oil; licorice; tartaric acid salts that were likely part of the aforementioned alcoholic concoction; and traces of spider flowers known to have medicinal properties.

Vessels of alabaster

Now we can add opiates to the list of pharmacological substances used by the ancient Egyptians. The authors of this latest paper focused on one alabaster vase in particular, housed in the Yale Peabody Museum’s Babylonian Collection. The vase is intact—a rare find—and is inscribed in four ancient languages and mentions Xerxes I, who reigned over the Achaemenid Empire from 486 to 465 BCE. The authors were particularly intrigued by the presence of a dark-brown residue inside the vase.

Papaver somnifera entry in a facsimile of the ca. 515 CE Anicia Juliana Codex of De materia medica by Dioscorides. C. Zollo/courtesy of Medical Historical Library, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

pXRF analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

FTIR analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

pXRF analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

FTIR analysis of YBC alabastra. Andrew J. Koh

Past scholars had speculated the vases most likely held cosmetics or perfumes, or perhaps hidden messages between the king and his officials. Yet there are also several known pharmacopeia recipes contained in such works as the Anicia Juliana Codex of De materia medica by Dioscorides. The current authors analyzed residue samples with nondestructive techniques, namely portable X-ray fluorescence XRF (pXRF) and passive Fourier Transform Infrared (pFTIR) spectroscopy.

The result: distinct traces of several biomarkers for opium, such as noscapine, hydrocotarnine, morphine, thebaine, and papaverine. That’s consistent with an earlier identification of opiate residues found in several Egyptian alabaster vessels and Cypriot juglets excavated from a merchant’s tomb south of Cairo, dating back to the New Kingdom (16th to 11th century BCE).

The authors think these twin findings warrant a reassessment of prior assumptions about Egyptian alabaster vessels, many of which they believe could also have traces of ancient opiates. A good starting point, they suggest, is a set of vessels excavated from Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 by archaeologist Howard Carter. Many of those vessels have the same sticky dark brown organic residues. There was an early attempt to chemically analyze those residues in 1933 by Albert Lucas, who simply didn’t have the necessary technology to identify the compounds, although he was able to determine that the residues were not unguents or perfumes. Nobody has attempted to analyze the residues since.

Additional evidence of the value of the residues lies in the fact that looters didn’t engage in the usual “smash and grab” practices employed to collect precious metals when it came to the alabaster vessels. Instead, looters transferred the organic stuff into portable bags; there are still finger marks inside many of the vessels, as well as remnants of the leather bags used to collect the organics.

“It remains imminently possible, if not probable, that at least some of the vast remaining bulk of calcite vessels… in fact contained opiates as part of a long-lived Egyptian tradition we are only beginning to understand,” the authors concluded. Looters missed a few of the vessels, which still contain their original organic contents, making them ideal candidates for future analysis.

“We now have found opiate chemical signatures that Egyptian alabaster vessels attached to elite societies in Mesopotamia and embedded in more ordinary cultural circumstances within ancient Egypt,” said co-author Andrew Koh of the Yale Peabody Museum. “It’s possible these vessels were easily recognizable cultural markers for opium use in ancient times, just as hookahs today are attached to shisha tobacco consumption. Analyzing the contents of the jars from King Tut’s tomb would further clarify the role of opium in these ancient societies.”

DOI: Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology, 2025. 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.13.3.0317 (About DOIs).