- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 38 911

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 2 093

Offline

One scientist says it's like buying a car and running it into a tree to save on gas money.

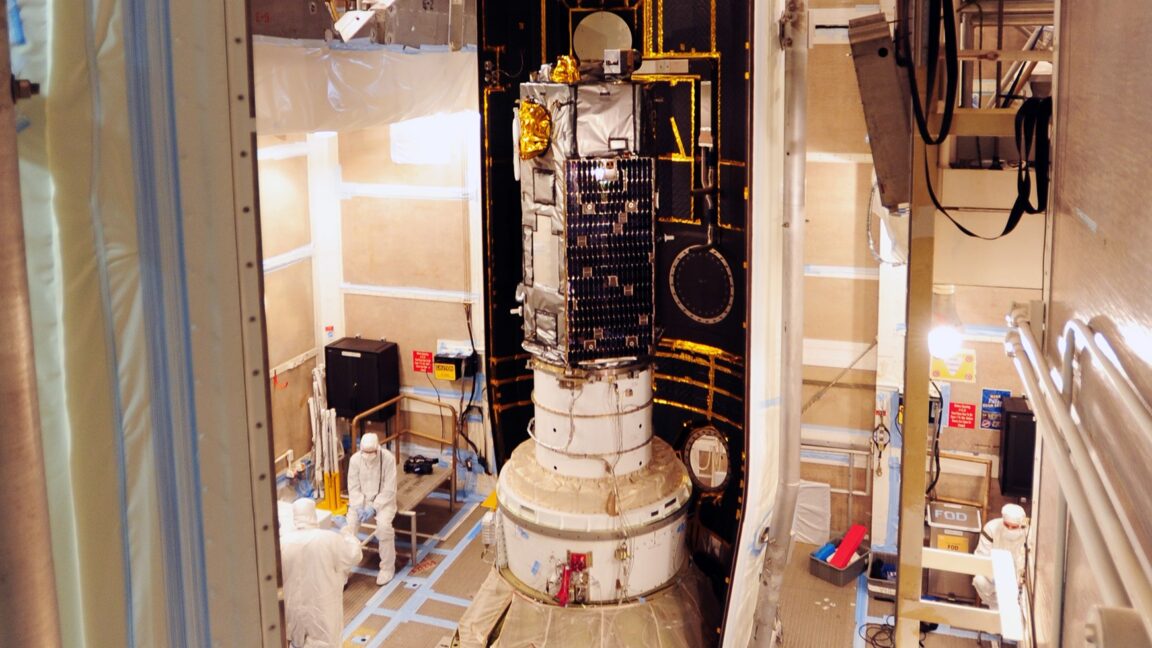

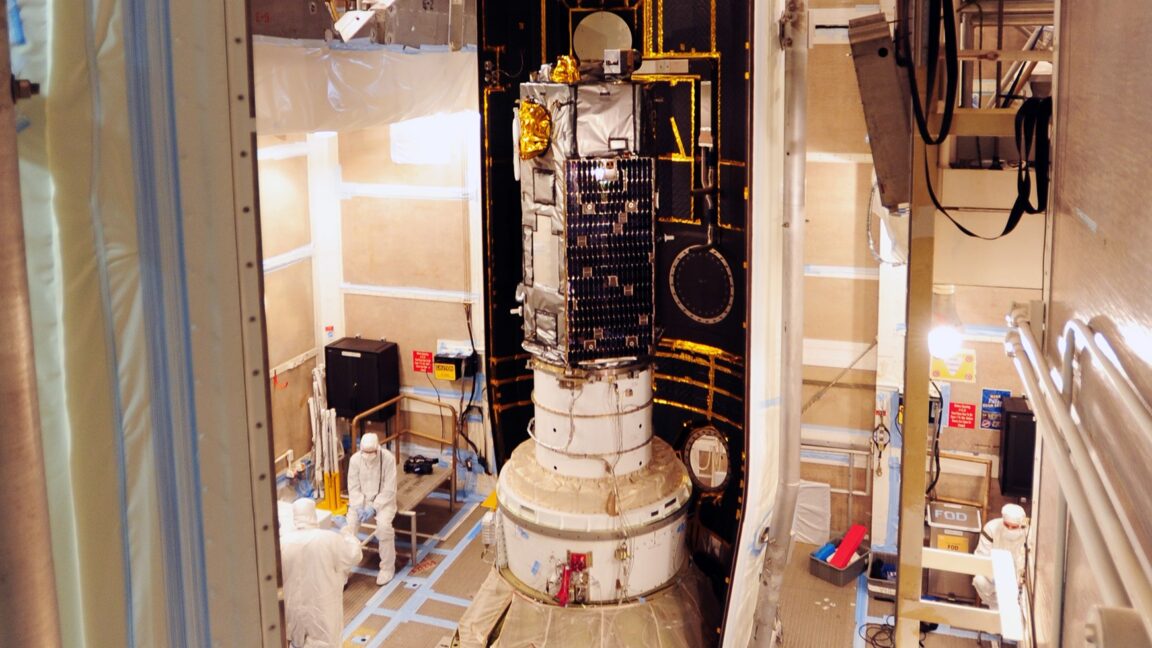

The Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 spacecraft, seen here before launch, rode a Delta II rocket into orbit from California on July 2, 2014. Credit: NASA/30th Space Wing, US Air Force

It was in 2002, during the George W. Bush administration, when NASA decided to put a satellite into orbit to track emissions of carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse gas pumped into the atmosphere through human activity.

After many twists and turns, NASA's 23-year remit of charting greenhouse gas emissions could come to a close as soon as the end of this month. President Donald Trump's budget request to Congress calls for terminating 41 of NASA's 124 science missions in development or operations, and another 17 would see their funding zeroed out in the near future. Overall, the proposed budget slashes NASA's spending by 25 percent and cuts NASA's science funding in half.

This year's federal budget runs out September 30, and although lawmakers from both parties have signaled they will reject most of Trump's cuts, it's far from certain that Congress will pass a budget for the next fiscal year before the looming deadline. The Trump administration, meanwhile, has directed NASA managers to make plans to close out the missions tagged for cancellation.

Without specific congressional direction, the White House would have a clear hand at implementing Trump's wishes. But even with a full appropriations bill, Trump's budget director, Russ Vought, could try to circumvent congressional will with so-called pocket rescissions. The White House is currently locked in a court battle over the legality of this practice, where the administration could refuse to spend money approved by Congress.

This all leaves NASA officials and scientists in a lurch. Two of the missions with uncertain futures monitor carbon dioxide levels in the Earth's atmosphere. US taxpayers paid more than $750 million to design, build, and launch the instruments, and killing the missions now would save roughly $16 million per year.

Dollars for pennies

David Crisp was one of NASA's leading atmospheric scientists until his retirement from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 2022. He told The New York Times that shutting down the agency's two operating Orbiting Carbon Observatory missions would be like buying a car "and then running it into a tree after a few years, just to save the price of a tank of gas."

"We built these satellites and got them approved and got taxpayer dollars to build them because they serve critical functions in commerce, in national security, in food security, in water security," Crisp told the Times.

Crisp first presented the idea for the Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO) at the turn of the century. NASA selected the proposal from a list of 18 mission concepts in 2002. The OCO mission enjoyed a relatively smooth ride through development, avoiding significant technical issues and remaining above the partisan hubbub in Washington, DC.

But all of that changed when the satellite launched in February 2009. A few minutes after liftoff, a protective shroud surrounding the OCO satellite clung to the rocket when it should have jettisoned. The mission was doomed, and the satellite crashed back to Earth. Within days, scientists began lobbying for a replacement. OCO's mission was to create the first global maps of the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide, places where the gas is emitted into the atmosphere and absorbed back into oceans and plants.

Artist's illustration of the OCO-3 instrument and its operating post on the International Space Station. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/David Hinkle

These measurements are fundamental to understanding how greenhouse gas emissions relate to rising temperatures, simultaneously contributing to scientific research and informing policymakers of compliance with environmental regulations.

NASA leadership took the rare step of approving a carbon copy of OCO less than a year after the 2009 launch failure. That's when the mission became a political football.

Republicans in the House of Representatives singled out the replacement mission, named OCO-2, for cancellation in 2011 as a target for deficit reduction. OCO-2 survived and made it to the launch pad in 2014. This time, the free-flying satellite rocketed into orbit with no issues and continues operating today.

Amplifying returns

OCO-2's measurements paint a complex picture. It's taken some time for scientists to learn how to interpret the data by separating out natural sources of natural carbon dioxide emissions from those caused by human activity. Similarly, OCO-2 has monitored locations where carbon is absorbed from the atmosphere, primarily tropical and boreal forests and oceans, along with artificial carbon capture installations.

The year after OCO-2's launch, NASA started planning to place a similar instrument on the outside of the International Space Station. The purpose of this follow-on mission, called OCO-3, was twofold: monitor carbon emissions at city scales with greater precision, and track changes in atmospheric concentrations of carbon throughout the course of a day.

Trump's first administration sought to cancel OCO-3 in 2017 and 2018. Lawmakers restored funding for OCO-3, and the instrument launched in 2019 in the trunk of a SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule.

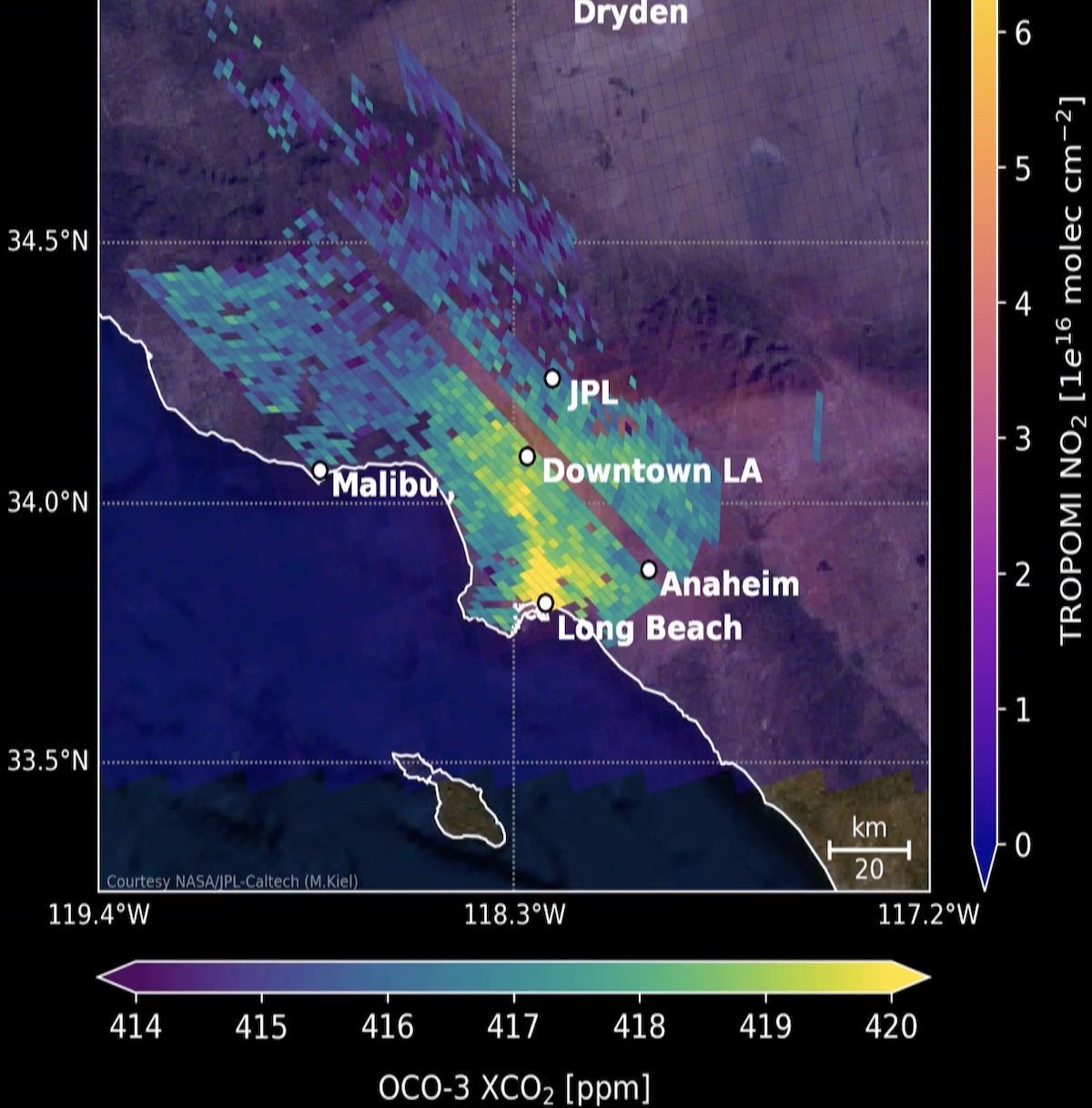

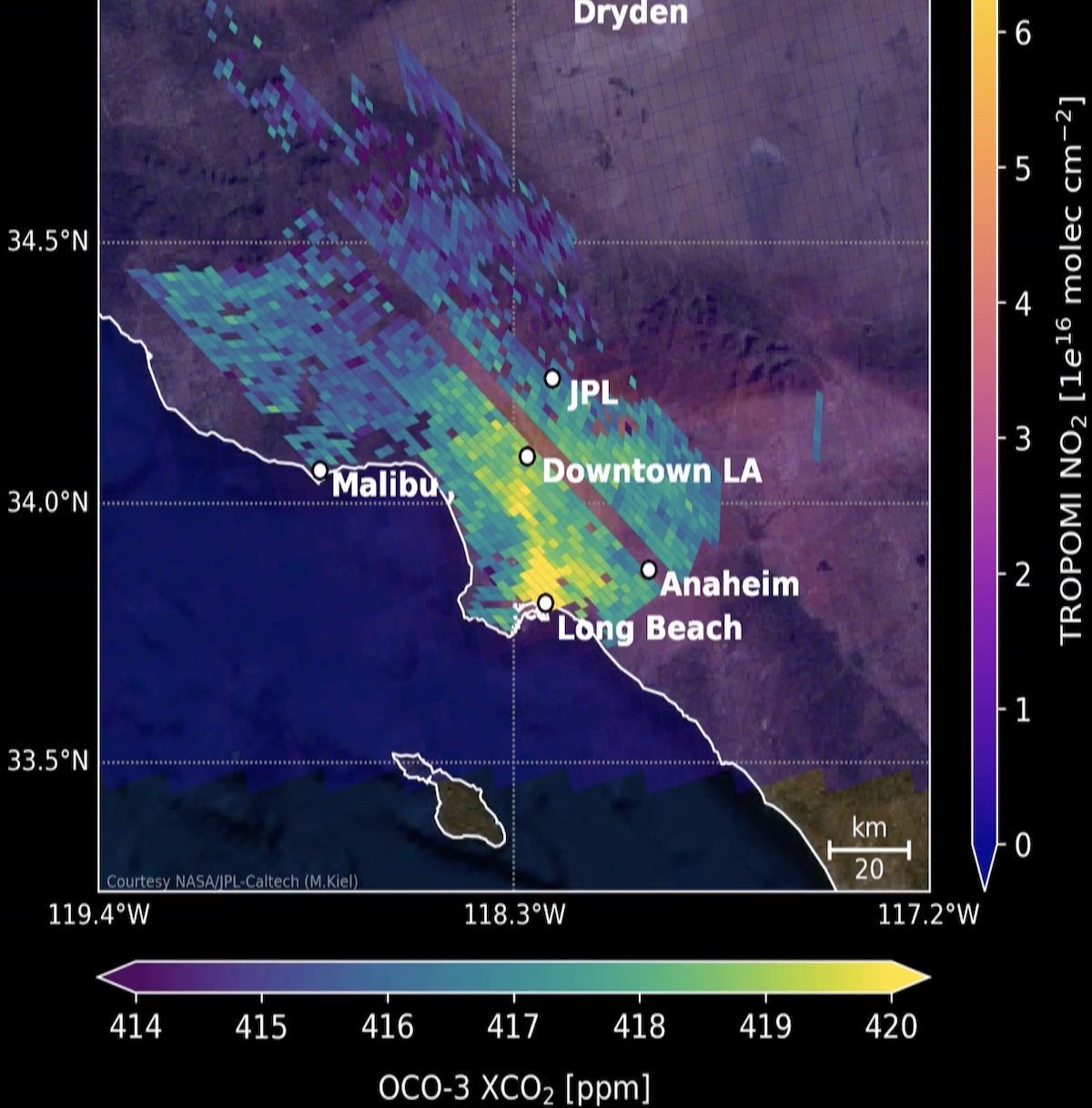

This snapshot of carbon dioxide concentrations over Los Angeles on February 19, 2021, was captured by NASA's OCO-3 instrument mounted on the International Space Station.

The OCO-2 and OCO-3 instruments observe the atmosphere from different vantage points in space. Scientists have combined data from both missions to pinpoint local sources of carbon dioxide, improving on the regional maps scientists proposed to produce with the original OCO mission.

These improved results have come out in the last few years. A study released in 2023 used OCO-2 and OCO-3 measurements to quantify the carbon dioxide discharged from a power station in Poland, the largest single emitter in Europe. A separate paper published earlier this year in Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres showed how scientists pinned down carbon emissions coming from even smaller point sources, such as a coal-fired power plant in Montana and oil sand processing facilities in Canada.

NASA's carbon-monitoring missions were never designed to detect carbon sources with such precision. "As a community we are refining the tools and techniques to be able to extract more information from the data than what we had originally planned," said Abhishek Chatterjee, OCO-3's project scientist at JPL, in a 2023 press release. "We are learning that we can actually understand a lot more about anthropogenic emissions than what we had previously expected."

Another unexpected bonus from the OCO missions, according to JPL, has been their ability to track growing seasons and crops by measuring the planet's photosynthesis.

Before satellite measurements, researchers relied on estimates and data from a smattering of air and ground-based sensors. An instrument on Mauna Loa, Hawaii, with the longest record of direct carbon dioxide measurements, is also slated for shutdown under Trump's budget.

It requires a sustained, consistent dataset to recognize trends. That's why, for example, the US government has funded a series of Landsat satellites since 1972 to create an uninterrupted data catalog illustrating changes in global land use.

But NASA is now poised to shut off OCO-2 and OCO-3 instead of thinking about how to replace them when they inevitably cease working. The missions are now operating beyond their original design lives, but scientists say both instruments are in good health.

Can anyone replace NASA?

Research institutes in Japan, China, and Europe have launched their own greenhouse gas-monitoring satellites. So far, all of them lack the spatial resolution of the OCO instruments, meaning they can't identify emission sources with the same precision as the US missions. A new European mission called CO2M will come closest to replicating OCO-2 and OCO-3, but it won't launch until 2027.

Several private groups have launched their own satellites to measure atmospheric chemicals, but these have primarily focused on detecting localized methane emissions for regulatory purposes, and not on global trends.

One of the newer groups in this sector, known as the Carbon Mapper Coalition, launched its first small satellite last year. This nonprofit consortium includes contributors from JPL, the same lab that spawned the OCO instruments, as well as Planet Labs, the California Air Resources Board, universities, and private investment funds.

Government leaders in Montgomery County, Maryland, have set a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent by 2027, and 100 percent by 2035. Mark Elrich, the Democratic county executive, said the pending termination of NASA's carbon-monitoring missions "weakens our ability to hold polluters accountable."

"This decision would ... wipe out years of research that helps us understand greenhouse gas emissions, plant health, and the forces that are driving climate change," Elrich said in a press conference last month.

The Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 spacecraft, seen here before launch, rode a Delta II rocket into orbit from California on July 2, 2014. Credit: NASA/30th Space Wing, US Air Force

It was in 2002, during the George W. Bush administration, when NASA decided to put a satellite into orbit to track emissions of carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse gas pumped into the atmosphere through human activity.

After many twists and turns, NASA's 23-year remit of charting greenhouse gas emissions could come to a close as soon as the end of this month. President Donald Trump's budget request to Congress calls for terminating 41 of NASA's 124 science missions in development or operations, and another 17 would see their funding zeroed out in the near future. Overall, the proposed budget slashes NASA's spending by 25 percent and cuts NASA's science funding in half.

This year's federal budget runs out September 30, and although lawmakers from both parties have signaled they will reject most of Trump's cuts, it's far from certain that Congress will pass a budget for the next fiscal year before the looming deadline. The Trump administration, meanwhile, has directed NASA managers to make plans to close out the missions tagged for cancellation.

Without specific congressional direction, the White House would have a clear hand at implementing Trump's wishes. But even with a full appropriations bill, Trump's budget director, Russ Vought, could try to circumvent congressional will with so-called pocket rescissions. The White House is currently locked in a court battle over the legality of this practice, where the administration could refuse to spend money approved by Congress.

This all leaves NASA officials and scientists in a lurch. Two of the missions with uncertain futures monitor carbon dioxide levels in the Earth's atmosphere. US taxpayers paid more than $750 million to design, build, and launch the instruments, and killing the missions now would save roughly $16 million per year.

Dollars for pennies

David Crisp was one of NASA's leading atmospheric scientists until his retirement from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 2022. He told The New York Times that shutting down the agency's two operating Orbiting Carbon Observatory missions would be like buying a car "and then running it into a tree after a few years, just to save the price of a tank of gas."

"We built these satellites and got them approved and got taxpayer dollars to build them because they serve critical functions in commerce, in national security, in food security, in water security," Crisp told the Times.

Crisp first presented the idea for the Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO) at the turn of the century. NASA selected the proposal from a list of 18 mission concepts in 2002. The OCO mission enjoyed a relatively smooth ride through development, avoiding significant technical issues and remaining above the partisan hubbub in Washington, DC.

But all of that changed when the satellite launched in February 2009. A few minutes after liftoff, a protective shroud surrounding the OCO satellite clung to the rocket when it should have jettisoned. The mission was doomed, and the satellite crashed back to Earth. Within days, scientists began lobbying for a replacement. OCO's mission was to create the first global maps of the sources and sinks of carbon dioxide, places where the gas is emitted into the atmosphere and absorbed back into oceans and plants.

Artist's illustration of the OCO-3 instrument and its operating post on the International Space Station. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/David Hinkle

These measurements are fundamental to understanding how greenhouse gas emissions relate to rising temperatures, simultaneously contributing to scientific research and informing policymakers of compliance with environmental regulations.

NASA leadership took the rare step of approving a carbon copy of OCO less than a year after the 2009 launch failure. That's when the mission became a political football.

Republicans in the House of Representatives singled out the replacement mission, named OCO-2, for cancellation in 2011 as a target for deficit reduction. OCO-2 survived and made it to the launch pad in 2014. This time, the free-flying satellite rocketed into orbit with no issues and continues operating today.

Amplifying returns

OCO-2's measurements paint a complex picture. It's taken some time for scientists to learn how to interpret the data by separating out natural sources of natural carbon dioxide emissions from those caused by human activity. Similarly, OCO-2 has monitored locations where carbon is absorbed from the atmosphere, primarily tropical and boreal forests and oceans, along with artificial carbon capture installations.

The year after OCO-2's launch, NASA started planning to place a similar instrument on the outside of the International Space Station. The purpose of this follow-on mission, called OCO-3, was twofold: monitor carbon emissions at city scales with greater precision, and track changes in atmospheric concentrations of carbon throughout the course of a day.

Trump's first administration sought to cancel OCO-3 in 2017 and 2018. Lawmakers restored funding for OCO-3, and the instrument launched in 2019 in the trunk of a SpaceX Dragon cargo capsule.

This snapshot of carbon dioxide concentrations over Los Angeles on February 19, 2021, was captured by NASA's OCO-3 instrument mounted on the International Space Station.

The OCO-2 and OCO-3 instruments observe the atmosphere from different vantage points in space. Scientists have combined data from both missions to pinpoint local sources of carbon dioxide, improving on the regional maps scientists proposed to produce with the original OCO mission.

These improved results have come out in the last few years. A study released in 2023 used OCO-2 and OCO-3 measurements to quantify the carbon dioxide discharged from a power station in Poland, the largest single emitter in Europe. A separate paper published earlier this year in Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres showed how scientists pinned down carbon emissions coming from even smaller point sources, such as a coal-fired power plant in Montana and oil sand processing facilities in Canada.

NASA's carbon-monitoring missions were never designed to detect carbon sources with such precision. "As a community we are refining the tools and techniques to be able to extract more information from the data than what we had originally planned," said Abhishek Chatterjee, OCO-3's project scientist at JPL, in a 2023 press release. "We are learning that we can actually understand a lot more about anthropogenic emissions than what we had previously expected."

Another unexpected bonus from the OCO missions, according to JPL, has been their ability to track growing seasons and crops by measuring the planet's photosynthesis.

Before satellite measurements, researchers relied on estimates and data from a smattering of air and ground-based sensors. An instrument on Mauna Loa, Hawaii, with the longest record of direct carbon dioxide measurements, is also slated for shutdown under Trump's budget.

It requires a sustained, consistent dataset to recognize trends. That's why, for example, the US government has funded a series of Landsat satellites since 1972 to create an uninterrupted data catalog illustrating changes in global land use.

But NASA is now poised to shut off OCO-2 and OCO-3 instead of thinking about how to replace them when they inevitably cease working. The missions are now operating beyond their original design lives, but scientists say both instruments are in good health.

Can anyone replace NASA?

Research institutes in Japan, China, and Europe have launched their own greenhouse gas-monitoring satellites. So far, all of them lack the spatial resolution of the OCO instruments, meaning they can't identify emission sources with the same precision as the US missions. A new European mission called CO2M will come closest to replicating OCO-2 and OCO-3, but it won't launch until 2027.

Several private groups have launched their own satellites to measure atmospheric chemicals, but these have primarily focused on detecting localized methane emissions for regulatory purposes, and not on global trends.

One of the newer groups in this sector, known as the Carbon Mapper Coalition, launched its first small satellite last year. This nonprofit consortium includes contributors from JPL, the same lab that spawned the OCO instruments, as well as Planet Labs, the California Air Resources Board, universities, and private investment funds.

Government leaders in Montgomery County, Maryland, have set a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent by 2027, and 100 percent by 2035. Mark Elrich, the Democratic county executive, said the pending termination of NASA's carbon-monitoring missions "weakens our ability to hold polluters accountable."

"This decision would ... wipe out years of research that helps us understand greenhouse gas emissions, plant health, and the forces that are driving climate change," Elrich said in a press conference last month.