- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 41 105

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

Children of the Sun burst onto the indie scene like a muzzle flash on a dark night. Publisher Devolver Digital dropped the game’s first trailer on February 1, showcasing frenzied sniper shots and a radioactive art style. A Steam demo highlighting its initial seven stages went live that same day and became a breakout hit during February’s Steam Next Fest. Two months later it landed in full and to broad acclaim. This explosive reveal and rapid release timeline mirrors the game itself — chaotic but contained, swift and direct, sharp and bright.

Though it feels like Children of the Sun popped into existence over the span of two months, it took solo developer René Rother more than 20 years to get here.

René Rother

As a kid in Berlin in the early 2000s, Rother was fascinated by the booming mod community. He spent his time messing around with free Counter-Strike mapping tools and Quake III mods from the demo discs tucked into his PC magazines. Rother daydreamed about having a job in game development, but it never felt like an attainable goal.

“It just didn't seem possible to make games,” he told Engadget. “It's like it was this huge black box.”

Rother couldn’t see an easy entry point until the 2010s, when mesh libraries and tools like GameMaker and Unity became more accessible. He discovered a fondness for creating 3D interactive art. But aside from some free online Javascript courses, he didn’t know how to program anything, so his output was limited.

“I dabbled into it a little bit, but then got kicked out. Again,” Rother said. “It was just like the whole entrance barrier was so big.”

René Rother

Rother pursued graphic design at university and he found the first two years fulfilling, with a focus on classical art training. By the end of his schooling, though, the lessons covered practical applications like working with clients, and Rother’s vision of a graphic design career smashed into reality.

“There was an eye-opening moment where I felt like, this is not for me,” Rother said.

In between classes, Rother was still making games for himself and for jams like Ludum Dare, steadily building up his skillset and cementing his reputation in these spaces as a master of mood.

“Atmospheric kind of pieces, walking simulators,” Rother said, recalling his early projects. “Atmosphere was very interesting to me to explore. But I never thought that it was actually something that could turn into a game. I never thought that it would become something that can be sold in a way that it's actually a product.”

René Rother

By the late 2010s Rother decided he was officially over graphic design and ready to try a job in game development. He applied to a bunch of studios and, in the meantime, picked up odd jobs at a supermarket and as a stagehand, setting up electronics. He eventually secured a gig as a 3D artist at a small studio in Berlin. Meanwhile, his pile of game jam projects and unfinished prototypes continued to grow.

“In that timeframe, Children of the Sun happened,” Rother said.

In Children of the Sun, players are The Girl, a woman who escaped the cult that raised her and is now enacting sniper-based revenge on all of its cells, one bullet at a time. In each round, players line up their shot and then control a single bullet as it ricochets through individual cult members. The challenge lies in finding the most speedy, efficient and stylish path of death, earning a spot at the top of the leaderboards.

“It was just a random prototype I started working on,” Rother said. “And one Saturday morning I was thinking, ‘I don't know what I'm doing with my life.'” With an atmospheric prototype and a head full of ennui, Rother emailed Devolver Digital that same day about potentially publishing Children of the Sun.

“The response was basically, ‘The pitch was shit but the game looks cool,’” Rother said. “And then it became a thing.”

René Rother

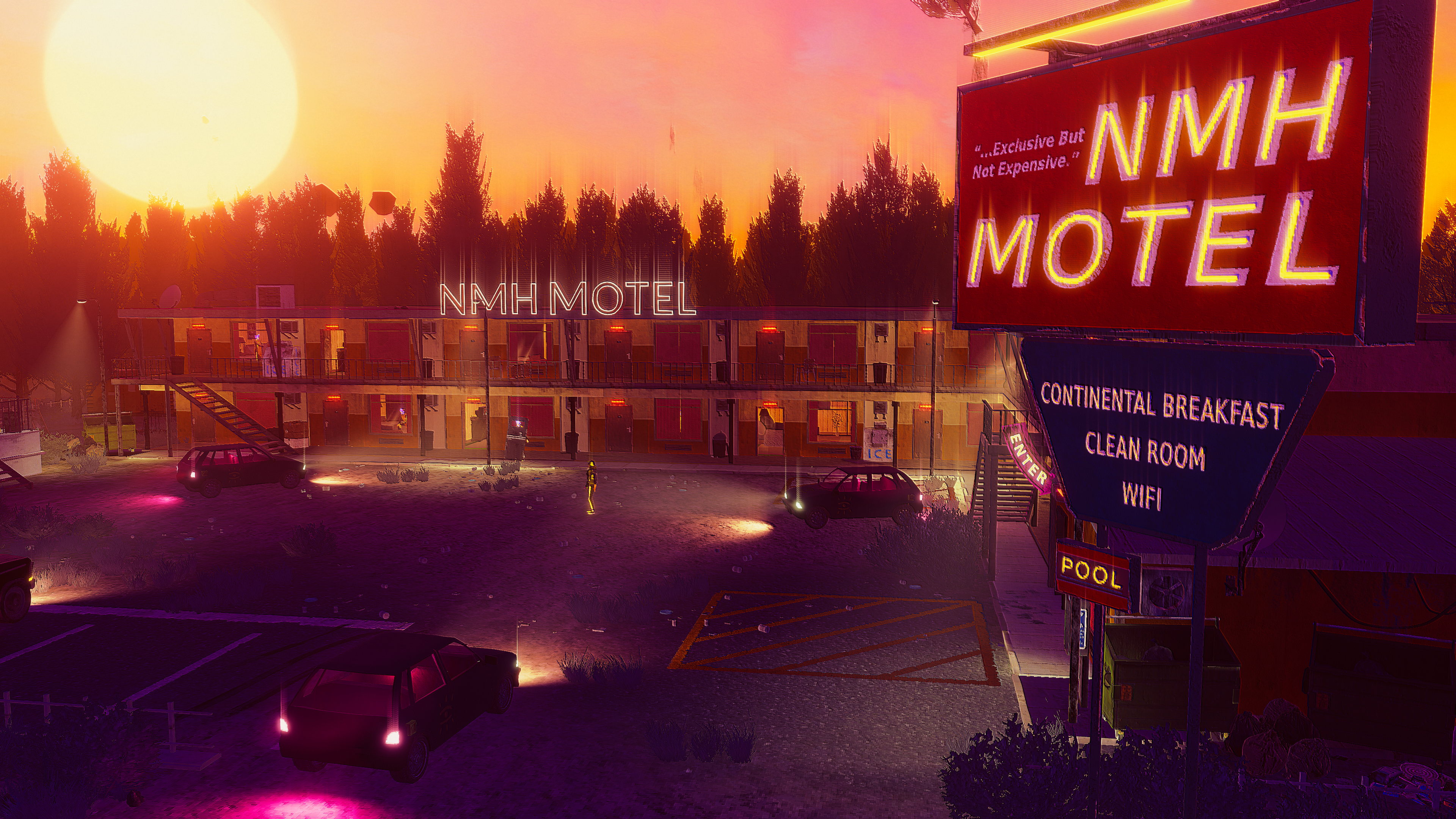

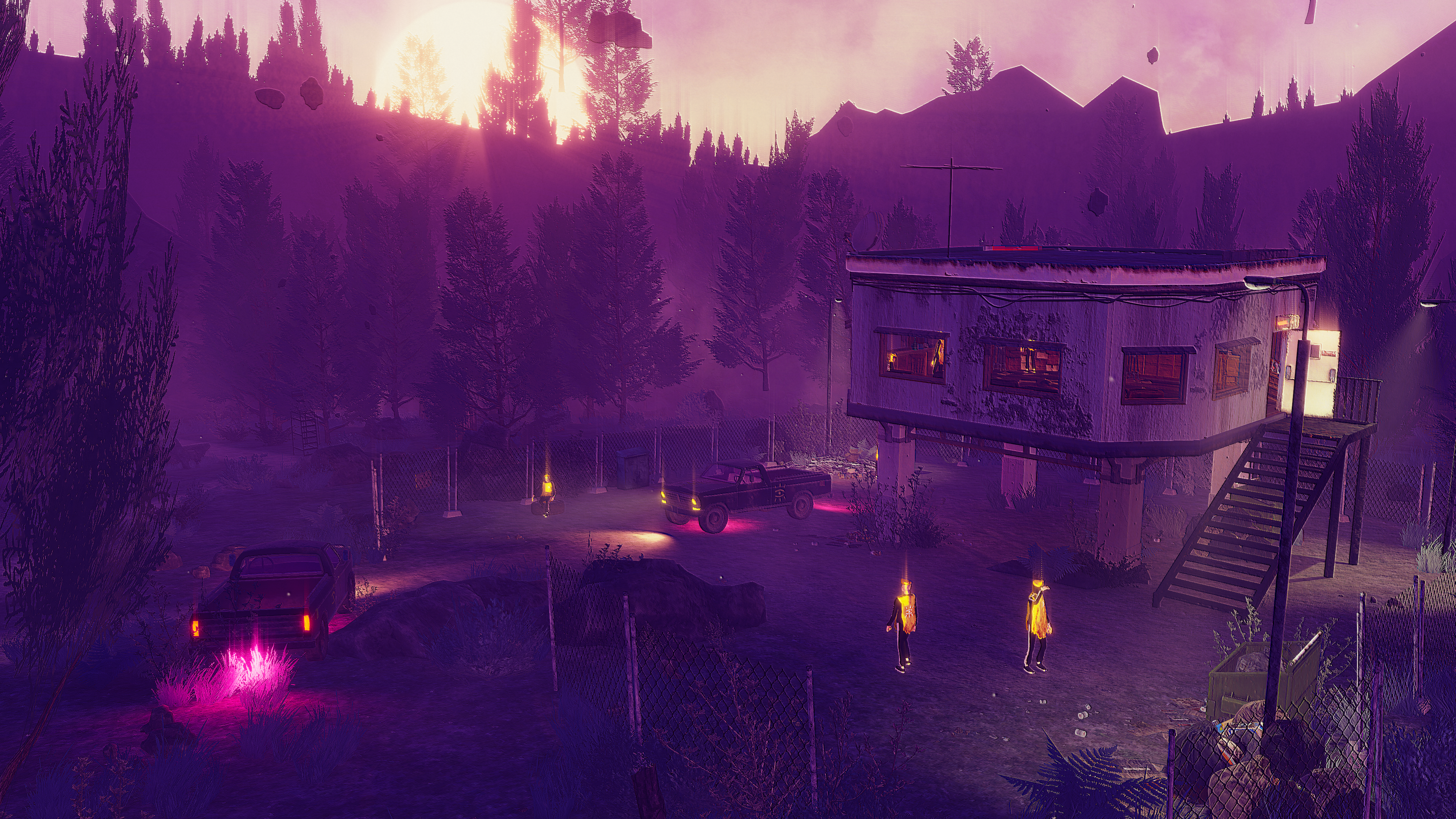

Visually, Children of the Sun is dazzling. It has a sketchy 3D art style that’s covered in bruise tones, with dark treelines, glowing yellow enemies and layers of texture. Every scene looks like The Girl just took a hit of adrenaline and her senses are on high alert, lending a hectic sense of hyper-vigilance to the entire experience. It’s a game built on instinct.

“I didn't make any mood boards,” Rother said. “I didn't prepare [for] it. It was just like, oh, let's make it this color. Ah, let's make it this color…. This is something to very easily get lost in. I spent a lot of time just adjusting the color of grass so it works well with the otherwise purplish tones and these kinds of things. I spent way too much time on the colors.”

Children of the Sun went through multiple visual iterations where Rother played with contrast, depth, fog density and traditional FPS color palettes, before landing on the game’s dreamlike and neon-drenched final form. The residue of this trial and error is still visible beneath Children of the Sun’s frames, and that’s exactly how Rother likes it.

“I see it as a big compliment, actually,” he said. “In paintings, when we talk about visual art, I really like when you can see the brushstrokes. I like when you can still see the lines of the pencil before the painting got made. I like the roughness. I wanted everything to be rough. I didn't want it to be polished.”

Rother picked up the game’s soundtrack collaborator, experimental ambient composer Aidan Baker, the same way he hooked up with Devolver. Rother was a fan of Baker and his band Nadja, and he wanted a similar droning, slowcore vibe as a backdrop for Children of the Sun. On a whim, Rother sent Baker a casual message asking if he’d like to make music for a video game.

“He was like, ‘Well I've never done it, so I don't know,’” Rother remembered. “So we met one evening and then afterwards he was like, ‘Yeah, let's just do it.’ Instead of just emulating something that I like in the game, I somehow managed to get straight to the source of it. And that was a really nice experience.”

For Rother, Children of the Sun has been a lesson in trusting his gut. He hasn’t found the proper word in English or German to describe the atmosphere he created in the game, but it’s something close to melancholy, spiked with an intense coiled energy and bright, psychedelic clarity. He just knows that it feels right — visuals, music, mechanics and all.

“That's kind of how I live my life,” Rother said. “Not that I'm, like, super spontaneous or just flip-flopping around with opinions or these kinds of things. It's more about doing things that feel right to me without necessarily knowing why.”

When he booted up that Quake III demo disc and started making 3D vignettes for game jams, Rother didn’t realize he was building the path that would eventually lead him to a major publishing deal, a collaboration with a musician he admires, a big Steam release and a game about cult sniping called Children of the Sun. When Rother takes a moment to survey his current lot in life, he feels lucky, he said.

René Rother

“I feel like in the last three years, somehow, lots of things fell into my lap,” Rother said. “Although I still had to do something for it. I needed to be prepared for this moment, that required work.… But in the time where I prepared myself, I was not aware that I was preparing myself. So that's how the feeling of luck gets amplified a bit more.”

“Luck” is one way to describe it, but “artistic instinct” might be just as fitting. Children of the Sun is available now on Steam for $15.

This article originally appeared on Engadget at https://www.engadget.com/it-took-20...e-an-overnight-success-194511363.html?src=rss

Though it feels like Children of the Sun popped into existence over the span of two months, it took solo developer René Rother more than 20 years to get here.

René Rother

As a kid in Berlin in the early 2000s, Rother was fascinated by the booming mod community. He spent his time messing around with free Counter-Strike mapping tools and Quake III mods from the demo discs tucked into his PC magazines. Rother daydreamed about having a job in game development, but it never felt like an attainable goal.

“It just didn't seem possible to make games,” he told Engadget. “It's like it was this huge black box.”

Rother couldn’t see an easy entry point until the 2010s, when mesh libraries and tools like GameMaker and Unity became more accessible. He discovered a fondness for creating 3D interactive art. But aside from some free online Javascript courses, he didn’t know how to program anything, so his output was limited.

“I dabbled into it a little bit, but then got kicked out. Again,” Rother said. “It was just like the whole entrance barrier was so big.”

René Rother

Rother pursued graphic design at university and he found the first two years fulfilling, with a focus on classical art training. By the end of his schooling, though, the lessons covered practical applications like working with clients, and Rother’s vision of a graphic design career smashed into reality.

“There was an eye-opening moment where I felt like, this is not for me,” Rother said.

In between classes, Rother was still making games for himself and for jams like Ludum Dare, steadily building up his skillset and cementing his reputation in these spaces as a master of mood.

“Atmospheric kind of pieces, walking simulators,” Rother said, recalling his early projects. “Atmosphere was very interesting to me to explore. But I never thought that it was actually something that could turn into a game. I never thought that it would become something that can be sold in a way that it's actually a product.”

René Rother

By the late 2010s Rother decided he was officially over graphic design and ready to try a job in game development. He applied to a bunch of studios and, in the meantime, picked up odd jobs at a supermarket and as a stagehand, setting up electronics. He eventually secured a gig as a 3D artist at a small studio in Berlin. Meanwhile, his pile of game jam projects and unfinished prototypes continued to grow.

“In that timeframe, Children of the Sun happened,” Rother said.

In Children of the Sun, players are The Girl, a woman who escaped the cult that raised her and is now enacting sniper-based revenge on all of its cells, one bullet at a time. In each round, players line up their shot and then control a single bullet as it ricochets through individual cult members. The challenge lies in finding the most speedy, efficient and stylish path of death, earning a spot at the top of the leaderboards.

“It was just a random prototype I started working on,” Rother said. “And one Saturday morning I was thinking, ‘I don't know what I'm doing with my life.'” With an atmospheric prototype and a head full of ennui, Rother emailed Devolver Digital that same day about potentially publishing Children of the Sun.

“The response was basically, ‘The pitch was shit but the game looks cool,’” Rother said. “And then it became a thing.”

René Rother

Visually, Children of the Sun is dazzling. It has a sketchy 3D art style that’s covered in bruise tones, with dark treelines, glowing yellow enemies and layers of texture. Every scene looks like The Girl just took a hit of adrenaline and her senses are on high alert, lending a hectic sense of hyper-vigilance to the entire experience. It’s a game built on instinct.

“I didn't make any mood boards,” Rother said. “I didn't prepare [for] it. It was just like, oh, let's make it this color. Ah, let's make it this color…. This is something to very easily get lost in. I spent a lot of time just adjusting the color of grass so it works well with the otherwise purplish tones and these kinds of things. I spent way too much time on the colors.”

Children of the Sun went through multiple visual iterations where Rother played with contrast, depth, fog density and traditional FPS color palettes, before landing on the game’s dreamlike and neon-drenched final form. The residue of this trial and error is still visible beneath Children of the Sun’s frames, and that’s exactly how Rother likes it.

“I see it as a big compliment, actually,” he said. “In paintings, when we talk about visual art, I really like when you can see the brushstrokes. I like when you can still see the lines of the pencil before the painting got made. I like the roughness. I wanted everything to be rough. I didn't want it to be polished.”

Rother picked up the game’s soundtrack collaborator, experimental ambient composer Aidan Baker, the same way he hooked up with Devolver. Rother was a fan of Baker and his band Nadja, and he wanted a similar droning, slowcore vibe as a backdrop for Children of the Sun. On a whim, Rother sent Baker a casual message asking if he’d like to make music for a video game.

“He was like, ‘Well I've never done it, so I don't know,’” Rother remembered. “So we met one evening and then afterwards he was like, ‘Yeah, let's just do it.’ Instead of just emulating something that I like in the game, I somehow managed to get straight to the source of it. And that was a really nice experience.”

For Rother, Children of the Sun has been a lesson in trusting his gut. He hasn’t found the proper word in English or German to describe the atmosphere he created in the game, but it’s something close to melancholy, spiked with an intense coiled energy and bright, psychedelic clarity. He just knows that it feels right — visuals, music, mechanics and all.

“That's kind of how I live my life,” Rother said. “Not that I'm, like, super spontaneous or just flip-flopping around with opinions or these kinds of things. It's more about doing things that feel right to me without necessarily knowing why.”

When he booted up that Quake III demo disc and started making 3D vignettes for game jams, Rother didn’t realize he was building the path that would eventually lead him to a major publishing deal, a collaboration with a musician he admires, a big Steam release and a game about cult sniping called Children of the Sun. When Rother takes a moment to survey his current lot in life, he feels lucky, he said.

René Rother

“I feel like in the last three years, somehow, lots of things fell into my lap,” Rother said. “Although I still had to do something for it. I needed to be prepared for this moment, that required work.… But in the time where I prepared myself, I was not aware that I was preparing myself. So that's how the feeling of luck gets amplified a bit more.”

“Luck” is one way to describe it, but “artistic instinct” might be just as fitting. Children of the Sun is available now on Steam for $15.

This article originally appeared on Engadget at https://www.engadget.com/it-took-20...e-an-overnight-success-194511363.html?src=rss