- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 844

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

“This particular anomaly deserves to be right up front and center for quite some time.”

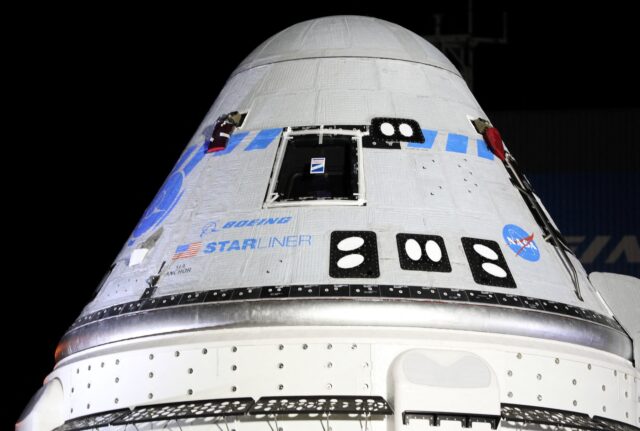

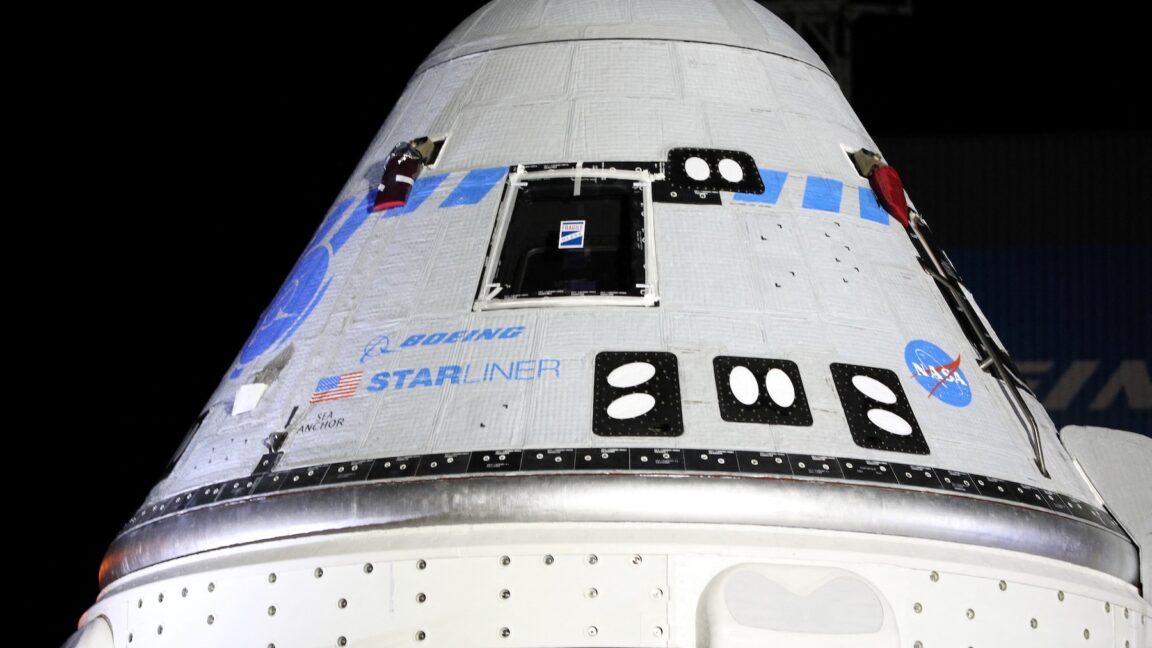

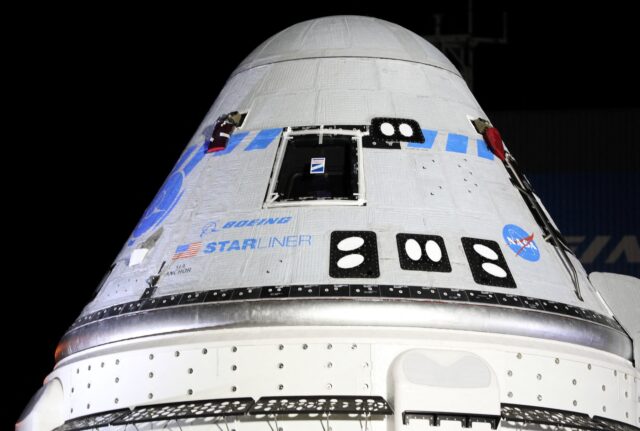

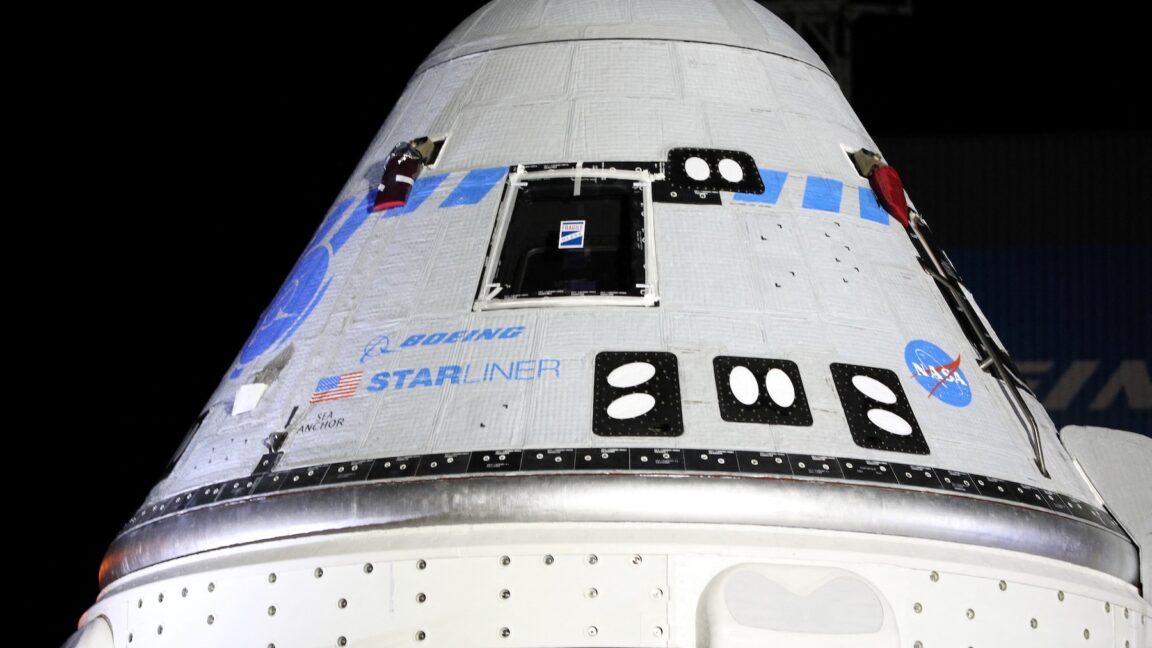

A detailed view of the CST-100 Starliner spacecraft at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida in 2021. Credit: Photo by Gregg Newton/AFP via Getty Images

For the better part of two months last year, most of us had no idea how serious the problems were with Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft docked at the International Space Station. A safety advisory panel found this uncertainty also filtered through NASA’s workforce.

On its first Crew Test Flight, Boeing’s Starliner delivered NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams to the space station in June 2024. They were the first people to fly to space on a Starliner spacecraft after more than a decade of development and setbacks. The astronauts expected to stay at the ISS for one or two weeks, but ended up remaining in orbit for nine months after NASA officials determined it was too risky to return them to Earth in the Boeing-built crew capsule. Wilmore and Williams flew back to Earth last March on a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft.

The Starliner capsule was beset by problems with its maneuvering thrusters and pernicious helium leaks on its 27-hour trip from the launch pad to the ISS. For a short time, Starliner commander Wilmore lost his ability to control the movements of his spacecraft as it moved in for docking at the station in June 2024. Engineers determined that some of the thrusters were overheating and eventually recovered most of their function, allowing Starliner to dock with the ISS.

“There was concern in real time that without recovery of some control, neither a docking nor a deorbit could be controllable, and that could have led to loss of vehicle and crew,” said Charlie Precourt, a former space shuttle commander and now a member of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP). “Given the severity of this anomaly, NASA wisely and correctly used the safe haven of the ISS to conduct testing and engineering on the ground to analyze the various recovery options.”

Confusion and uncertainty

Throughout that summer, managers from NASA and Boeing repeatedly stated that the spacecraft was safe to bring Wilmore and Williams home if the station needed to be evacuated in an emergency. But officials on the ground ordered extensive testing to understand the root of the problems. Buried behind the headlines, there was a real chance NASA managers would decide—as they ultimately did—not to put astronauts on Boeing’s crew capsule when it was time to depart the ISS.

Precourt said officials from Boeing and NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, which oversees the agency’s Starliner contract, “were signaling return on Starliner was the expected outcome” for Wilmore and Williams. “Other NASA entities in the decision process were not in concurrence,” Precourt continued. “As a result, there was significant stress on the workforce, with many believing the sole objective was to determine a means by which we could enable crew return on the Starliner.”

It would have been better, Precourt and other panel members said Friday, if NASA made a formal declaration of an in-flight “mishap” or “high visibility close call” soon after the Starliner spacecraft’s troubled rendezvous with the ISS. Such a declaration would have elevated responsibility for the investigation to NASA’s safety office.

“The ASAP finding is the lack of a declared in-flight mishap or high visibility close call contributed to an extensive, excessive … period of time where risk ownership and the decision-making authority were unclear,” Precourt said.

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft backs away from the International Space Station on September 6, 2024, without its crew. Credit: NASA

NASA procedural requirements stipulate that the agency should declare a mishap in the event of an injury, destruction of property, or mission failure. A high visibility close call is an incident senior NASA leaders “judge to possess a high degree of programmatic impact or public, media, or political interest, including, but are not limited to, mishaps and close calls that impact flight hardware, flight software, or completion of critical mission milestones.”

This is familiar territory for the Starliner program. NASA declared a high-visibility close call following Starliner’s first unpiloted test flight after it failed to reach the space station in 2019. Before then, NASA used the designation after the near-drowning of astronaut Luca Parmitano on a spacewalk in 2013.

The designation formally initiates an internal process within NASA’s safety office to launch an investigation and serves as a way to document and retain lessons learned for future programs. “Procedurally, investigation reports are tied to anomaly declaration, so they gain an official status in NASA records,” Precourt said. “Certainly, this particular anomaly deserves to be right up front and center for quite some time.”

Invoking the designation also ensures an independent investigation detached from the teams involved in the incident itself, according to retired Air Force Lt. Gen. Susan Helms, chair of the safety panel. “We just, I think, are advocates of safety investigation best practices, and that clearly is one of the top best practices,” Helms said.

Another member of the safety panel, Mark Sirangelo, said NASA should formally declare mishaps and close calls as soon as possible. “It allows for the investigative team to be starting to be formed a lot sooner, which makes them more effective and makes the results quicker for everyone,” Sirangelo said.

In the case of last year’s Starliner test flight, NASA’s decision not to declare a mishap or close call created confusion within the agency, safety officials said.

A few weeks into the Starliner test flight last year, the manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, Steve Stich, told reporters the agency’s plan was “to continue to return [the astronauts] on Starliner and return them home at the right time.” Mark Nappi, then Boeing’s Starliner program manager, regularly appeared to downplay the seriousness of the thruster issues during press conferences throughout Starliner’s nearly three-month mission.

“Specifically, there’s a significant difference, philosophically, between we will work toward proving the Starliner is safe for crew return, versus a philosophy of Starliner is no-go for return, and the primary path is on an alternate vehicle, such as Dragon or Soyuz, unless and until we learn how to ensure the on-orbit failures won’t recur on entry with the Starliner,” Precourt said.

“The latter would have been the more appropriate direction,” he said. “However, there were many stakeholders that believed the direction was the former approach. This ambiguity continued throughout the summer months, while engineers and managers pursued multiple test protocols in the Starliner propulsion systems, undoubtedly affecting the workforce.”

After months of testing and analysis, NASA officials were unsure if the thruster problems would recur on Starliner’s flight home. They decided in August 2024 to return the spacecraft to the ground without the astronauts, and the capsule safely landed in New Mexico the following month. The next Starliner flight will carry only cargo to the ISS.

The safety panel recommended that NASA review its criteria and processes to ensure the language is “unambiguous” in requiring the agency to declare an in-flight mishap or a high-visibility close call for any event involving NASA personnel “that leads to an impact on crew or spacecraft safety.”

A detailed view of the CST-100 Starliner spacecraft at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida in 2021. Credit: Photo by Gregg Newton/AFP via Getty Images

For the better part of two months last year, most of us had no idea how serious the problems were with Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft docked at the International Space Station. A safety advisory panel found this uncertainty also filtered through NASA’s workforce.

On its first Crew Test Flight, Boeing’s Starliner delivered NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams to the space station in June 2024. They were the first people to fly to space on a Starliner spacecraft after more than a decade of development and setbacks. The astronauts expected to stay at the ISS for one or two weeks, but ended up remaining in orbit for nine months after NASA officials determined it was too risky to return them to Earth in the Boeing-built crew capsule. Wilmore and Williams flew back to Earth last March on a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft.

The Starliner capsule was beset by problems with its maneuvering thrusters and pernicious helium leaks on its 27-hour trip from the launch pad to the ISS. For a short time, Starliner commander Wilmore lost his ability to control the movements of his spacecraft as it moved in for docking at the station in June 2024. Engineers determined that some of the thrusters were overheating and eventually recovered most of their function, allowing Starliner to dock with the ISS.

“There was concern in real time that without recovery of some control, neither a docking nor a deorbit could be controllable, and that could have led to loss of vehicle and crew,” said Charlie Precourt, a former space shuttle commander and now a member of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP). “Given the severity of this anomaly, NASA wisely and correctly used the safe haven of the ISS to conduct testing and engineering on the ground to analyze the various recovery options.”

Confusion and uncertainty

Throughout that summer, managers from NASA and Boeing repeatedly stated that the spacecraft was safe to bring Wilmore and Williams home if the station needed to be evacuated in an emergency. But officials on the ground ordered extensive testing to understand the root of the problems. Buried behind the headlines, there was a real chance NASA managers would decide—as they ultimately did—not to put astronauts on Boeing’s crew capsule when it was time to depart the ISS.

Precourt said officials from Boeing and NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, which oversees the agency’s Starliner contract, “were signaling return on Starliner was the expected outcome” for Wilmore and Williams. “Other NASA entities in the decision process were not in concurrence,” Precourt continued. “As a result, there was significant stress on the workforce, with many believing the sole objective was to determine a means by which we could enable crew return on the Starliner.”

It would have been better, Precourt and other panel members said Friday, if NASA made a formal declaration of an in-flight “mishap” or “high visibility close call” soon after the Starliner spacecraft’s troubled rendezvous with the ISS. Such a declaration would have elevated responsibility for the investigation to NASA’s safety office.

“The ASAP finding is the lack of a declared in-flight mishap or high visibility close call contributed to an extensive, excessive … period of time where risk ownership and the decision-making authority were unclear,” Precourt said.

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft backs away from the International Space Station on September 6, 2024, without its crew. Credit: NASA

NASA procedural requirements stipulate that the agency should declare a mishap in the event of an injury, destruction of property, or mission failure. A high visibility close call is an incident senior NASA leaders “judge to possess a high degree of programmatic impact or public, media, or political interest, including, but are not limited to, mishaps and close calls that impact flight hardware, flight software, or completion of critical mission milestones.”

This is familiar territory for the Starliner program. NASA declared a high-visibility close call following Starliner’s first unpiloted test flight after it failed to reach the space station in 2019. Before then, NASA used the designation after the near-drowning of astronaut Luca Parmitano on a spacewalk in 2013.

The designation formally initiates an internal process within NASA’s safety office to launch an investigation and serves as a way to document and retain lessons learned for future programs. “Procedurally, investigation reports are tied to anomaly declaration, so they gain an official status in NASA records,” Precourt said. “Certainly, this particular anomaly deserves to be right up front and center for quite some time.”

Invoking the designation also ensures an independent investigation detached from the teams involved in the incident itself, according to retired Air Force Lt. Gen. Susan Helms, chair of the safety panel. “We just, I think, are advocates of safety investigation best practices, and that clearly is one of the top best practices,” Helms said.

Another member of the safety panel, Mark Sirangelo, said NASA should formally declare mishaps and close calls as soon as possible. “It allows for the investigative team to be starting to be formed a lot sooner, which makes them more effective and makes the results quicker for everyone,” Sirangelo said.

In the case of last year’s Starliner test flight, NASA’s decision not to declare a mishap or close call created confusion within the agency, safety officials said.

A few weeks into the Starliner test flight last year, the manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, Steve Stich, told reporters the agency’s plan was “to continue to return [the astronauts] on Starliner and return them home at the right time.” Mark Nappi, then Boeing’s Starliner program manager, regularly appeared to downplay the seriousness of the thruster issues during press conferences throughout Starliner’s nearly three-month mission.

“Specifically, there’s a significant difference, philosophically, between we will work toward proving the Starliner is safe for crew return, versus a philosophy of Starliner is no-go for return, and the primary path is on an alternate vehicle, such as Dragon or Soyuz, unless and until we learn how to ensure the on-orbit failures won’t recur on entry with the Starliner,” Precourt said.

“The latter would have been the more appropriate direction,” he said. “However, there were many stakeholders that believed the direction was the former approach. This ambiguity continued throughout the summer months, while engineers and managers pursued multiple test protocols in the Starliner propulsion systems, undoubtedly affecting the workforce.”

After months of testing and analysis, NASA officials were unsure if the thruster problems would recur on Starliner’s flight home. They decided in August 2024 to return the spacecraft to the ground without the astronauts, and the capsule safely landed in New Mexico the following month. The next Starliner flight will carry only cargo to the ISS.

The safety panel recommended that NASA review its criteria and processes to ensure the language is “unambiguous” in requiring the agency to declare an in-flight mishap or a high-visibility close call for any event involving NASA personnel “that leads to an impact on crew or spacecraft safety.”