- Регистрация

- 17 Февраль 2018

- Сообщения

- 40 948

- Лучшие ответы

- 0

- Реакции

- 0

- Баллы

- 8 093

Offline

Hunter-gatherers probably derived the poison from the milky bulb extract of a Boophone disticha plant.

Poison arrows or darts are sometimes depicted in such films as Apocalypto (2006). Credit: Touchstone Pictures

Poisoned arrows or darts have long been used by cultures all over the world for hunting or warfare. For example, there are recipes for poisoning projective weapons, and deploying them in battle, in Greek and Roman historical documents, as well as references in Greek mythology and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Chinese warriors over the ages did the same, as did the Gauls and Scythians, and some Native American populations.

Archaeologists have now found traces of a plant-based poison on several 60,000-year-old quartz Stone Age arrowheads found in South Africa, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances. That would make this the oldest direct evidence of using poisons on projectiles—a cognitively complex hunting strategy—and pushes the timeline for using poison arrows back into the Pleistocene.

The poisons commonly used could be derived from plants or animals (frogs, beetles, venomous lizards). Plant-based examples include curare, a muscle relaxant that paralyzes the victim’s respiratory system, causing death by asphyxiation. Oleander, milkweeds, or inee (onaye) contain cardiac glucosides. In Southeast Asia, the sap or juice of seeds from the ancar tree is smeared on arrowheads, which causes paralysis, convulsions, and cardiac arrest thanks to the presence of toxins like strychnine. Several species of aconite are known for their use as arrow poisons in Siberia and northern Japan.

According to the authors, up until now, the earliest direct evidence of poisoned arrows dates back to the mid-Holocene. For instance, scientists found traces of toxic glycoside residues on 4,000-year-old bone-tipped arrows recovered from an Egyptian tomb, as well as on bone arrow points from 6,700 years ago excavated from South Africa’s Kruger Cave. The only prior evidence of using poisons for hunting during the Pleistocene is a “poison applicator” found at Border Cave in South Africa, along with a lump of beeswax.

Milk of the poisonous onion

The authors sampled 10 quartz-backed arrowheads recovered from the Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter site in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The results revealed that five of the 10 tested tips had traces of compounds found in Boophone disticha, aka gifbol (poisonous onion), sometimes called the century plant, which is common throughout South Africa. Various parts of the plant have been used as an analgesic (specifically a volatile oil called eugenol) as well as for poisonous hunting purposes. Its more toxic compounds include buphandrine, crinamidine, and buphanine; the latter is similar in effect to scopolamine and can cause hallucinations, coma, or death.

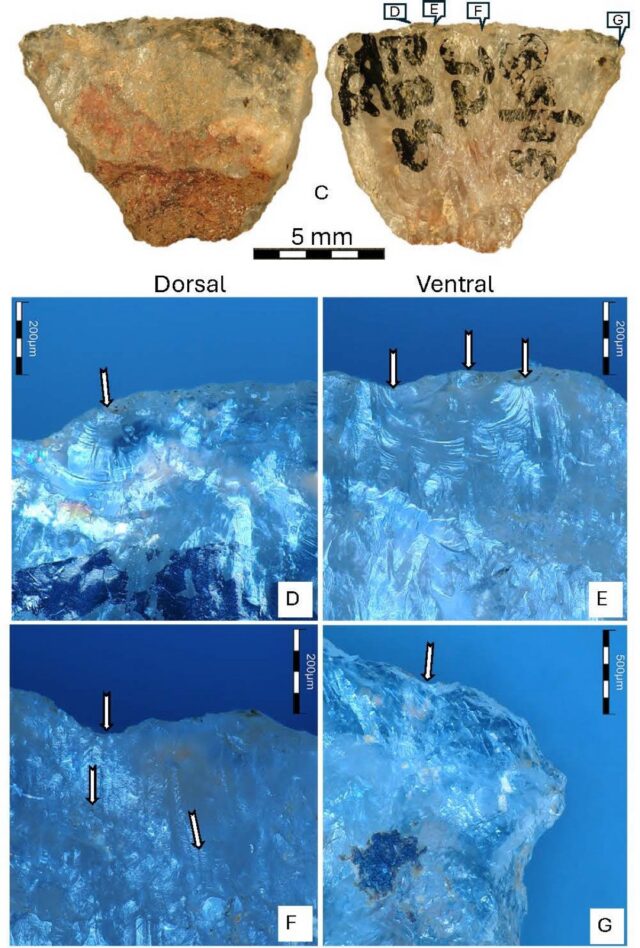

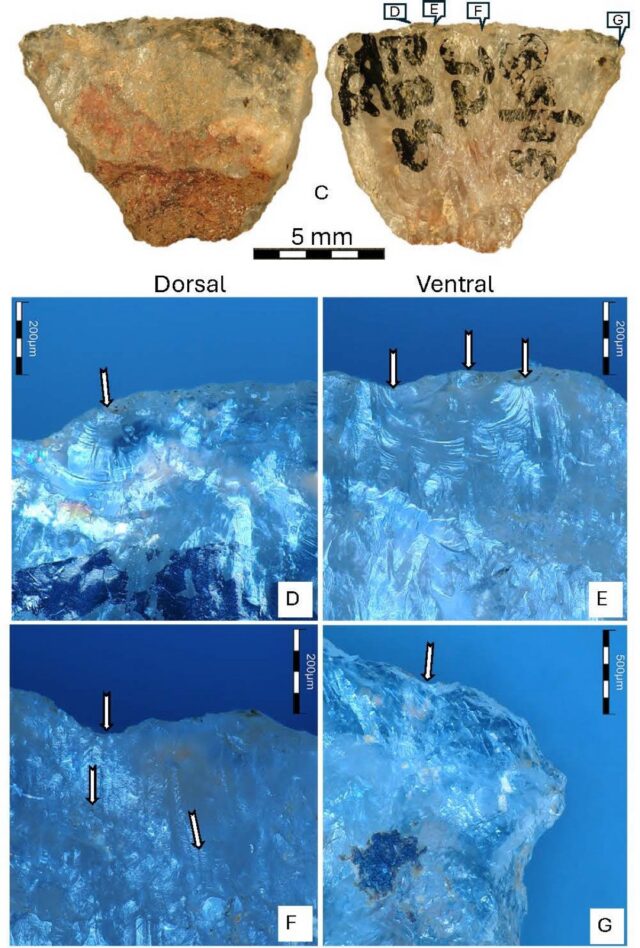

Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter backed microlith 001. Credit: Sven Isaksson et al. 2026

The new analysis specifically identified alkaloid residues of buphandrine and epibuphanisine. This cannot be coincidence, per the authors. “If I speculate, Boophone poison was probably discovered by people eating the bulbs and then becoming sick or dying from it,” co-author Marlize Lombard of University of Johannesburg in South Africa told New Scientist. “The plant also has preservative, antibacterial and hallucinatory properties, so that it is used in traditional medicine, and human deaths still occur as a result of accidental overdosing.”

The hunter-gatherers who made the arrow tips probably derived the poison from the milky bulb extract of a B. disticha plant. The thick liquid can be dried in the sun until it has a gum-like consistency, or reduced by heating it over a fire. Even small amounts of this substance have proven lethal to rodents within 30 minutes. In humans, it causes nausea, coma, flaccid muscles, rapid pulse rates, labored breathing, and edema of the lungs depending on the dosage. (Small doses can have medicinal effects.)

The authors note that poison arrows are not meant to kill instantly on impact. Rather, the intent is to pierce the skin just enough to introduce the poison into the bloodstream, with the arrowhead breaking off on impact and remaining under an animal’s skin. The wounded animal would then run for a day or more as the hunters continued to track them. This is evidence of complex cognition, per the authors, suggesting advanced planning, abstraction, and causal reasoning.

Historical 18th century records describe how the plant was used for hunting purposes, such as Carl Peter Thunberg’s account of native hunters using the root of B. disticha to poison arrows for hunting game like springbok. For comparison purposes, the authors also analyzed 250-year-old arrowheads found in collections in Sweden, brought back from South Africa by travelers. Those arrowheads also had traces of the same type of poison.

“Finding traces of the same poison on both prehistoric and historical arrowheads was crucial,” said co-author Sven Isaksson of Stockholm University. “By carefully studying the chemical structure of the substances and thus drawing conclusions about their properties, we were able to determine that these particular substances are stable enough to survive this long in the ground. It’s also fascinating that people had such a deep and long-standing understanding of the use of plants.”

DOI: Science Advances, 2025. 10.1126/sciadv.adz3281 (About DOIs).

Poison arrows or darts are sometimes depicted in such films as Apocalypto (2006). Credit: Touchstone Pictures

Poisoned arrows or darts have long been used by cultures all over the world for hunting or warfare. For example, there are recipes for poisoning projective weapons, and deploying them in battle, in Greek and Roman historical documents, as well as references in Greek mythology and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Chinese warriors over the ages did the same, as did the Gauls and Scythians, and some Native American populations.

Archaeologists have now found traces of a plant-based poison on several 60,000-year-old quartz Stone Age arrowheads found in South Africa, according to a new paper published in the journal Science Advances. That would make this the oldest direct evidence of using poisons on projectiles—a cognitively complex hunting strategy—and pushes the timeline for using poison arrows back into the Pleistocene.

The poisons commonly used could be derived from plants or animals (frogs, beetles, venomous lizards). Plant-based examples include curare, a muscle relaxant that paralyzes the victim’s respiratory system, causing death by asphyxiation. Oleander, milkweeds, or inee (onaye) contain cardiac glucosides. In Southeast Asia, the sap or juice of seeds from the ancar tree is smeared on arrowheads, which causes paralysis, convulsions, and cardiac arrest thanks to the presence of toxins like strychnine. Several species of aconite are known for their use as arrow poisons in Siberia and northern Japan.

According to the authors, up until now, the earliest direct evidence of poisoned arrows dates back to the mid-Holocene. For instance, scientists found traces of toxic glycoside residues on 4,000-year-old bone-tipped arrows recovered from an Egyptian tomb, as well as on bone arrow points from 6,700 years ago excavated from South Africa’s Kruger Cave. The only prior evidence of using poisons for hunting during the Pleistocene is a “poison applicator” found at Border Cave in South Africa, along with a lump of beeswax.

Milk of the poisonous onion

The authors sampled 10 quartz-backed arrowheads recovered from the Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter site in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The results revealed that five of the 10 tested tips had traces of compounds found in Boophone disticha, aka gifbol (poisonous onion), sometimes called the century plant, which is common throughout South Africa. Various parts of the plant have been used as an analgesic (specifically a volatile oil called eugenol) as well as for poisonous hunting purposes. Its more toxic compounds include buphandrine, crinamidine, and buphanine; the latter is similar in effect to scopolamine and can cause hallucinations, coma, or death.

Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter backed microlith 001. Credit: Sven Isaksson et al. 2026

The new analysis specifically identified alkaloid residues of buphandrine and epibuphanisine. This cannot be coincidence, per the authors. “If I speculate, Boophone poison was probably discovered by people eating the bulbs and then becoming sick or dying from it,” co-author Marlize Lombard of University of Johannesburg in South Africa told New Scientist. “The plant also has preservative, antibacterial and hallucinatory properties, so that it is used in traditional medicine, and human deaths still occur as a result of accidental overdosing.”

The hunter-gatherers who made the arrow tips probably derived the poison from the milky bulb extract of a B. disticha plant. The thick liquid can be dried in the sun until it has a gum-like consistency, or reduced by heating it over a fire. Even small amounts of this substance have proven lethal to rodents within 30 minutes. In humans, it causes nausea, coma, flaccid muscles, rapid pulse rates, labored breathing, and edema of the lungs depending on the dosage. (Small doses can have medicinal effects.)

The authors note that poison arrows are not meant to kill instantly on impact. Rather, the intent is to pierce the skin just enough to introduce the poison into the bloodstream, with the arrowhead breaking off on impact and remaining under an animal’s skin. The wounded animal would then run for a day or more as the hunters continued to track them. This is evidence of complex cognition, per the authors, suggesting advanced planning, abstraction, and causal reasoning.

Historical 18th century records describe how the plant was used for hunting purposes, such as Carl Peter Thunberg’s account of native hunters using the root of B. disticha to poison arrows for hunting game like springbok. For comparison purposes, the authors also analyzed 250-year-old arrowheads found in collections in Sweden, brought back from South Africa by travelers. Those arrowheads also had traces of the same type of poison.

“Finding traces of the same poison on both prehistoric and historical arrowheads was crucial,” said co-author Sven Isaksson of Stockholm University. “By carefully studying the chemical structure of the substances and thus drawing conclusions about their properties, we were able to determine that these particular substances are stable enough to survive this long in the ground. It’s also fascinating that people had such a deep and long-standing understanding of the use of plants.”

DOI: Science Advances, 2025. 10.1126/sciadv.adz3281 (About DOIs).